Newsletter 117

May 2021

WELCOME, TENA KOUTOU KATOA, KIA ORANA, TALOFA LAVA, MALO LELEI, FAKAALOFA ATU.

Welcome to the May 2021 issue of the MSCC’s Newsletter

This newsletter is the first one that has been published by MSCC in the last 10 months. Since July 2020, I have been trying to muster the enthusiasm needed to put together another newsletter, but this canary was silenced, exhausted and overwhelmed from reading and sounding the alarm, about the harms arising from our dependence on routine technologies and medications into the normal physiological process of childbirth.

MSCC and I have been chirping out warnings about the fear-based culture of maternity service provision in AotearoaNZ for decades. Regular readers of this newsletter will know that we have consistently encouraged women to embrace their inherent ability to grow and give birth to a healthy baby and make informed choices about their maternity experiences from a place of confidence rather than a place of fear.

Regular readers of this newsletter will know that we have consistently encouraged women to embrace their inherent ability to grow and give birth to a healthy baby and make informed choices about their maternity experiences from a place of confidence rather than a place of fear

It has become obvious that our increasingly interventionist system of maternity service provision is causing physical and mental harm to women, their babies and to many midwifery providers. For decades now, research has been warning us that the routine application of maternity care technologies, disempowers and damages women and sees many embarking on motherhood feeling unconfident and carrying physical and mental scars.

In this edition we look at the, frankly appalling, statistics in the latest maternity clinical indicators report; we give a brief history of the international research and recommendations that have been sounding warnings and making recommendations that support the physiologically normal in childbirth and; we applaud on the work of the Birth Time documentary makers who are hoping to use modern visual technology to inspire and empower women to take back their birth rights and birth rites.

Brenda Hinton

A Brief Herstory of Birth in the Technological Era

In 1979, UN International Year of the Child, the WHO Regional Committee for Europe expressed concern about: the rapidly expanding technology being applied to birth and its associated costs; the doubling/tripling of the caesarean section rate during the 1970s in many countries, including the question of whether this was associated with the increasing use of electronic fetal heart rate monitoring; and the increasingly vocal demands from women and women’s organisations for control over their bodies and birth experiences.

More than 40 years later, maternity intervention rates continue to soar even though concerns have continued to be voiced across the spectrum midwifery & obstetric organisations to mainstream medical institutions and publications. Let’s take a quick look at some of these and the (failed) recommendations they have made over the past 4-plus decades.

Joint Interregional Conference on Appropriate Technology for Birth (1985)

A raft of recommendations were unanimously adopted by the international delegates in attendance at this WHO sponsored conference, including:

- that each woman has a fundamental right to maternity care;

- that each woman has a central role in all aspects of her care from planning to evaluation;

- a recognition that social, emotional and psychological factors are integral to maternity care;

- that training of professional midwives should be promoted and that care during normal pregnancy and birth, and following birth should be the duty of this profession;

- that countries should develop the potential to evaluate birth care technology rates and effects, and that the women, on whom the technology is used, should be involved in this assessment and evaluation.

It would seem that we here in AotearoaNZ did pretty well in integrating these recommendations into our maternity service in the decade from the late 1980s with the exception of the last bullet point. We’ve certainly recorded and reported on our maternity intervention rates but the Ministry of Health (MoH) has not commissioned a Maternity Consumer Survey since 2014 and these surveys have never asked questions about women’s involvement with or expectations of the management of pregnancy care in their communities and the maternity facilities available to them. Although some of our District Health Boards (DHBs) have consumer committees, the consumers (usually co-opted) onto these, generally have no specific background in maternity and neither support from, nor accountability to, any maternity consumer organisation or any group of maternity service consumers. Neither the MoH nor any DHB has involved maternity consumers in the introduction or evaluation, of maternity interventions. This meeting also recommended that information about birth practices/intervention rates in individual hospitals/maternity facilities (rates of caesarean section, etc) should be provided to the birthing population they served. As far as MSCC is aware, National Women’s Health in Auckland is the only DHB that consistently publishes a comprehensive and accessible annual report of their maternity outcomes. Most other DHBs report on only the 20 Maternity Clinical Indicators as part of their annual Maternity Quality and Safety Annual Reports, as is required by their contracts with the MoH.

What are appropriate rates of intervention?

Delegates at this 1985 conference, made evidence-based recommendations, including epidemiologically supported rates for some maternity interventions:

- there is no evidence of benefit from routine electronic fetal heartrate monitoring during labour;

- women should not be put in a lithotomy position during labour and birth – they should be encouraged to walk about and freely decide which position to adopt for birthing;

- the systematic use of episiotomy is not justified;

- labour should be induced only in response to specific medical indications, not for convenience and based on epidemiological evidence, no geographic region should have rates of induced labour over 10%;

- the routine administration of analgesic or anaesthetic drugs, that are not specifically required to correct or prevent a complication during labour, should be avoided;

• routine artificial rupture of the membranes in early labour, is not scientifically justified;

• epidemiological evidence shows that there is no justification for any geographic region to have more than a 10-15 % caesarean section rate* and that there is no evidence that a caesarean section is required after a previous transverse low segment caesarean section birth.

The delegates further agreed to encourage their governments to adopt implementation strategies including that:

· governments should identify, departments within their health ministries to take charge of promoting and coordinating the assessment of appropriate technology;

· that funding agencies should use financial regulation to discourage the indiscriminate use of technology;

· the results of the assessment of birth technology should be widely disseminated, to change the behaviour of professionals and inform the decisions of maternity care consumers.

It was hoped that if these recommendations were acted on they would change the culture of birth and stem the tide of technological interference into the primal physiological processes of pregnancy, labour and birth and early mothering. The delegates could not have known the impact that our growing romance with, dependence on and subservience to, technology would have on the day-to-day lives of humans and the provision of maternity services in every country in the world.

*World Health Organization

Statement on Caesarean Section Rates

As medical intervention rates have soared in many countries, some health authorities and health professionals have sought to justify rates above those recommended by WHO in 1985, questioning their validity in contemporary times, by saying that women had changed, that the health of women had deteriorated, that birthing women were now “older, fatter & sicker” and therefore required more maternity interventions including, specifically, a higher rate of c-section.

These justifications prompted The Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO) to state:- “Over the past three decades, as more evidence on the benefits and risks of caesarean section has accumulated, along with significant improvements in clinical obstetric care and in the methodologies to assess evidence and issue recommendations, health care professionals, scientists, epidemiologists and policy-makers have increasingly expressed the need to revisit the 1985 recommended rate …” To address c-section rate claim, WHO conducted two studies: a systematic review of studies available in the scientific literature which analyse the association between caesarean section rates and maternal, perinatal and infant outcomes and a worldwide study to assess the association between caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality. The results were assessed by a panel of international experts at a consultation convened by WHO in 2014 who issued the following conclusions:

“Based on the available data and using internationally accepted methods to assess the evidence with the most appropriate analytical techniques, WHO concludes:

- Caesarean sections are effective in saving maternity and infant lives, but only when they are required for medically indicated reasons.

- At a population level, caesarean section rates higher than 10% are not associated with reductions in maternal and newborn mortality rates

- Caesarean sections can cause significant and sometimes permanent complications, disability or death particularly in settings that lack the facilities and/or capacity to conduct safe surgery and treat surgical complications. Caesarean sections should ideally only be undertaken when medically necessary.

- Every effort should be make to provide caesarean sections to women in need rather than striving to achieve a specific rate.

- The effects of caesarean section rates on other outcomes, such as maternal and perinatal morbidity, paediatric outcomes, and psychological or social well-being are still unclear. More research is needed to understand the health effects of caesarean section on immediate and future outcomes.“

*World Health Organization. (2015). WHO statement on caesarean section rates. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/161442 WHO reference number: WHO/RHR/15.02

Too little too late, too much too soon.

The Lancet Maternal Health Series (2016)

In 2016 the Lancet Medical Journal published a new series of six papers that analysed current knowledge about the drivers and detractors of maternal health and in the process coined the phrase; Too little, too late or too much, too soon,” to describe the current state of maternity care provision in just about every country in the world.

The Executive Summary “reporting on experiences from across all regions. For women using services, some receive excellent care but too many experience one of two extremes: too little, too late or too much, too soon. Both extremes represent maternal health care that isnot grounded in evidence. And other women receive no care at all.” Poor quality care that is too little, too late can jeopardise the health of women and their babies, while the overuse of maternity medical interventions, too much, too soon, can cause harm, increase health costs, and contribute to a culture of disrespect and abuse.

Their analysis showed that in many middle and high income countries, both extremes of maternal health care can be found. Increasingly maternity statistics and outcomes show these inequities; vulnerable populations accessing and receiving less care so experiencing higher rates of morbidity and mortality, while wealthier populations, in particular those accessing private maternity care, are over-treated and are also experiencing increasing rates of maternal physical and mental morbidities and infant morbidities. In summary, the authors make the statement that “access to evidence-based care remains inadequate across all settings…”, a situation that exists in many of our maternity hospitals and that MSCC has been raising concerns about for the past 30 years.

New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators 2018[1]

This 2018 report is not accompanied by any MoH analysis or commentary of the published data. The downloadable “Background Document” simply tells us what a clinical indicator is and the purpose of collecting this data.

What is a clinical indicator?

A clinical indicator measures the clinical management and outcome of health care received by an individual. For each clinical indicator, there should be evidence that confirms the underlying causal relationship between a particular process or intervention and a health outcome (AIHW 2019). Clinical indicators can enable the quality of care and services to be measured and compared, by describing a performance or health outcome that should occur, and then evaluating whether it has occurred, in a standardised format that enables comparison between services or sites (Mainz 2003).” (New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators Background Document pg1)

The purpose of the New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators is to:

- highlight areas where quality and safety could be improved nationally

- support quality improvement by helping DHBs to identify focus areas for local clinical review of maternity services

- provide a broader picture of maternity outcomes in New Zealand than from maternal and perinatal mortality data alone

- provide standardised (benchmarked) data allowing DHBs to evaluate their maternity services over time and against the national average

- improve national consistency and quality in maternity data reporting.

(New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators Background Document pp1-2)

MSCC wonders if any facilities or DHBs are instituting any changes in service design and provision to help achieve the purpose defined in the first three bullet points above. This MoH report provides no information about any follow-up or actual requirement for accountability from individual DHBs or maternity facilities. Reading individual DHBs annual Maternity Quality and Safety Reports which include their rates of the Maternity Clinical Indicators, reveals that DHBs do little more than present justifications for their intervention rates. There are sometimes vague references to investigating this or that, but as in this national report, there is no data or discussion about whether these increasing rates of interventions can be either justified by a similar increase in improved outcomes for mothers and babies or supported by any evidence. It would seem that the DHBs are neither required nor motivated to reduce either, the personal costs of increased interventions to women and their babies, or the financial costs to our health system of overtreatment.

The failure of maternity services provided in most facilities throughout the country to provide improved quality and safety and evidence-based care, is glaringly obvious in outcomes for Standard Primiparae, a group of low risk first time mothers who are defined as follows:-

Standard primiparae (pg6) a group of women considered to be clinically comparable and expected to require low levels of obstetric intervention are defined as women who:-

- are aged between 20 and 34 years (inclusive) at birth

- are pregnant with a single baby presenting in labour in cephalic position

- have no known prior pregnancy of 20 weeks and over gestation

- give birth to a live or stillborn baby at term gestation: between 37 and 41 weeks inclusive

- have no recorded obstetric complications in the present pregnancy that are indications for specific obstetric interventions (our emphasis)

According to the report only approximately 15 percent of all women giving birth in AotearoaNZ meet the above definition – Surely we need to investigate why it is that in a high income country we have so few women expecting their first baby are considered healthy and low risk?

It could reasonably be expected that this (small) group of women would require few, if any interventions during their labours and births. Unfortunately the data belies this assumption and the intervention rates for these low/no risk first time mothers at most of our maternity facilities has continued to increase to unacceptable and unnecessary levels.

MSCC would like the MoH and the individual facilities to answer the following questions:-

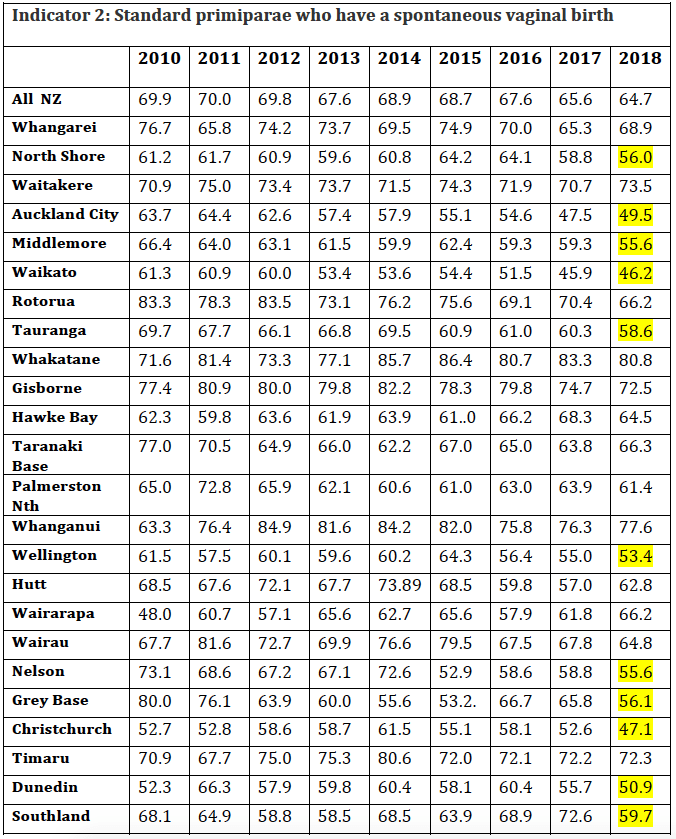

- Why is our maternity service not able to support even two-thirds of these low/no risk first time mothers to give birth spontaneously?

- Why it is that barely half of low risk, first time mothers who birth in our larger hospitals (highlighted) are provided with care that allows them to have a spontaneous vaginal birth? These statistics alone in our opinion should be sufficient to trigger a major review and restructure of the “care” provided by our maternity facilities. Are low risk, first time mothers who book to birth in these facilities made aware that they have around a 50:50 chance that their babies will be cut or pulled out of their bodies?

- Has there been any research and analysis of the culture and practices in those (few) facilities that support a significantly greater percentage (20 – 30% higher) of women to birth vaginally than our biggest maternity hospitals?

- Are facilities required to investigate and report on staffing or protocol changes, facilities upgrade, new initiatives etc when their statistics suddenly vary? E.g. In Whanganui from 2012 to 2015 over 80% of standard primigravidae birthed vaginally – what happened after 2015 that caused the rate to drop so significantly? Why is it that the largest maternity facility, seemingly erroneously called National Women’s Health, has had such appalling and continually worsening outcomes for this group of women, including a reduction of around 15% in the numbers of low risk first time mothers being supported to birth vaginally in less than a decade?! This is particularly concerning when a few kilometres away in West Auckland, the smaller Waitakere Maternity Unit has consistently been able to ensure that a significantly higher percentage (>20% more) of low/no risk first time mothers give birth vaginally (and even then , MSCC would consider the 73.5% vaginal birth rate for this group of women, too low).

- What are the Ministry of Health, the DHBs and individual maternity facilities management doing to reverse the practices and culture that are obviously leading to fewer and fewer women, including low/no risk women, experiencing anything like a physiological birth?

Indicator 2: Standard primiparae who have a spontaneous vaginal birth

“This indicator measures the proportion of women having a spontaneous (non-instrumental) vaginal birth in a low-risk population. This measure includes births for which labour was augmented or induced. Maternity service providers should review, evaluate and make necessary changes to clinical practice aimed at supporting women to achieve a spontaneous vaginal birth.” (New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators: Background Document pg9).

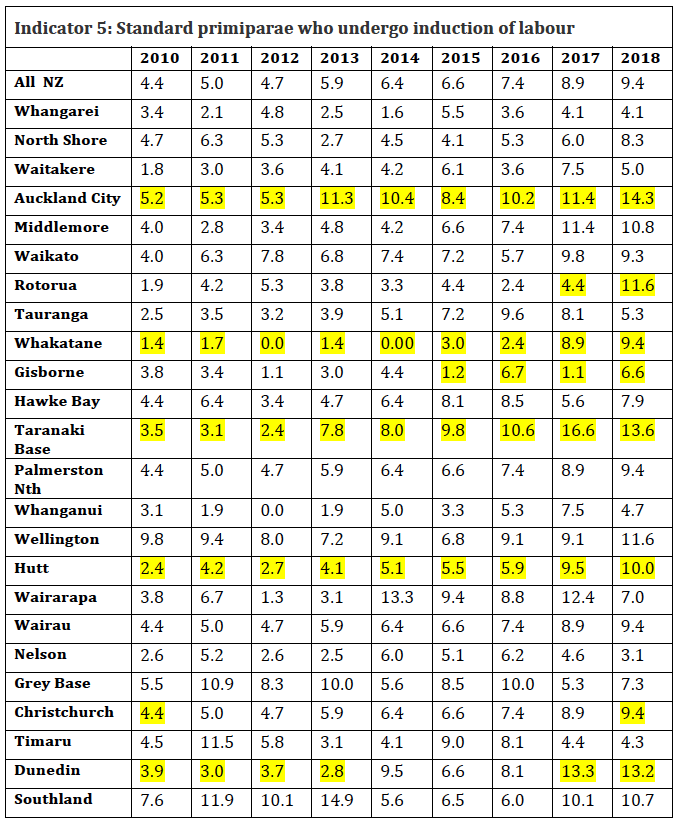

Indicator 5: Standard primiparae who undergo an induction of labour

“The purpose of indicator 5 (induction of labour) is to benchmark rates of induction of labour in a low-risk population. Induction of labour is associated with risk of fetal distress, uterine hyper-stimulation and postpartum haemorrhage, and can be the start of a cascade of further medical interventions (AIHW 2013). Maternity service providers should use this indicator in further investigation of their policies and practices with respect to inducing labour in low-risk women. If a provider’s rates of induction of labour are significantly higherthan its peer group at a national level, it should review the appropriateness of inductions in this group …”(New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators: Background Document pg10)

Even though these induction of labour rates might seem reassuringly low compared with the national rate for induction of labour (the Report on Maternity 2017* tells us that 25.5% of women who experienced labour, i.e. excluding the additional 12.6% that had an elective c-section, had their labours induced), MSCC would ask, why is it that any low/no risk women are having their labours induced? It seems like the medical equivalent of an oxymoron to say that you have no risk factors but your labour needs to be induced even though the evidence shows that this will increase your risk of “fetal distress, uterine hyper-stimulation and postpartum haemorrhage, and can be the start of a cascade of further medical interventions”. Why are these rates being allowed to rise seemingly unchecked?

*www.health.govt.nz/publication/report-maternity-2017

Has the MoH investigated the doubling of the overall induction of labour rate between 2010 and 2018, for this group of women with no risk factors? Has the MoH required any accountability for the practices, protocols or approvals that have seen an increase in inductions of labour for this low/no risk group of mothers, in e.g. Rotorua where the rate has increased from 1.9% to 11.6%; or Dunedin (3.9% to 13.2%); or Taranaki Base (3.5% to 13.6%) or in the many other facilities that have doubled their rate of induction of labour for these women, who have no obstetric risk factors, in less than 10 years?!

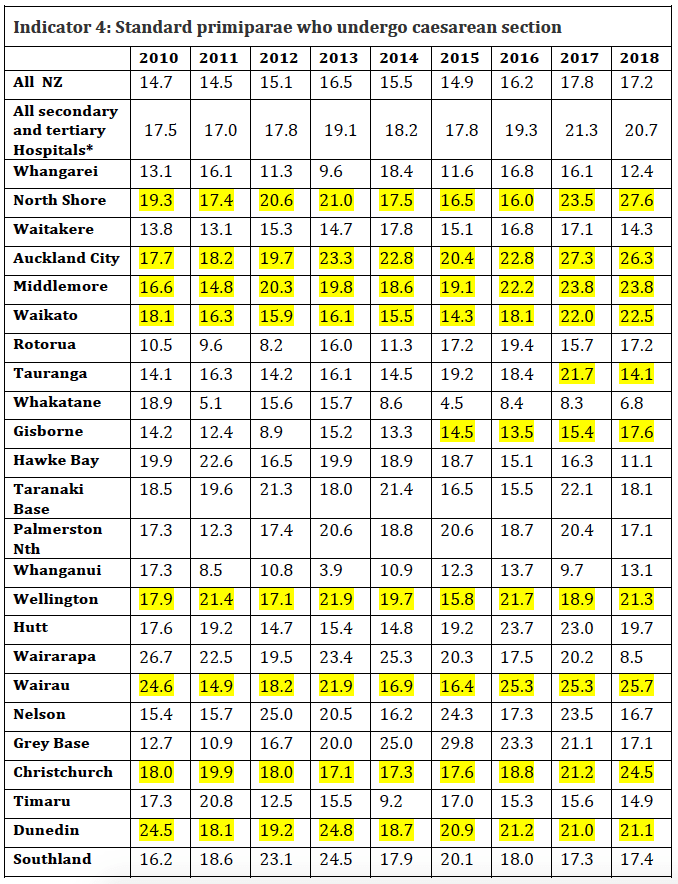

Indicator 4: Standard primiparae who undergo caesarean section

“The purpose of indicator 4 (caesarean section) is to encourage maternity service providers to evaluate whether caesarean sections were performed on the right women at the right place and at the right time, and to reduce the harm associated with potentially avoidable caesarean sections among low-risk women.” (New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators: Background Document pg10)

* These percentages are more accurate because the denominator is all standard primigravidae who gave birth in a secondary or tertiary hospital where caesarean section is able to be performed. The denominator in the top row is all standard primigravidae who gave birth including those who gave birth at home or in a Primary Birthing Unit where caesarean section is not a possibility.

Surely those managing and funding our maternity hospitals have been investigating why it is that, first time mothers with no obstetric risk factors, who give birth in a secondary or tertiary hospital now have a 20.7% (>1:5 ) chance of having a surgical birth?

What changes are the growing number of hospitals whose c-section rate for standard primiparae is over 10% (the upper limit that WHO epidemiological studies show can be justified by any improvement in maternal or infant mortality), putting in place to reduce the harm associated with their rates of surgical birth which are clearly not evidence-based? Maybe our big hospitals should investigate policies and procedures at Whakatane Hospital where the c-section rate for standard primigravidae has more than halved since 2010 and has been held at a rate of <10% for this group of women for the past 5 years.

Does the MoH require any explanation or analysis from facilities like Wairarapa Hospital whose c-section rate for standard primigravidae reduced by more than 50% from 2017 to 2018? i.e. Has this facility made changes that could be replicated elsewhere or is this a reporting error or statistical blip rather than a sustainable result?

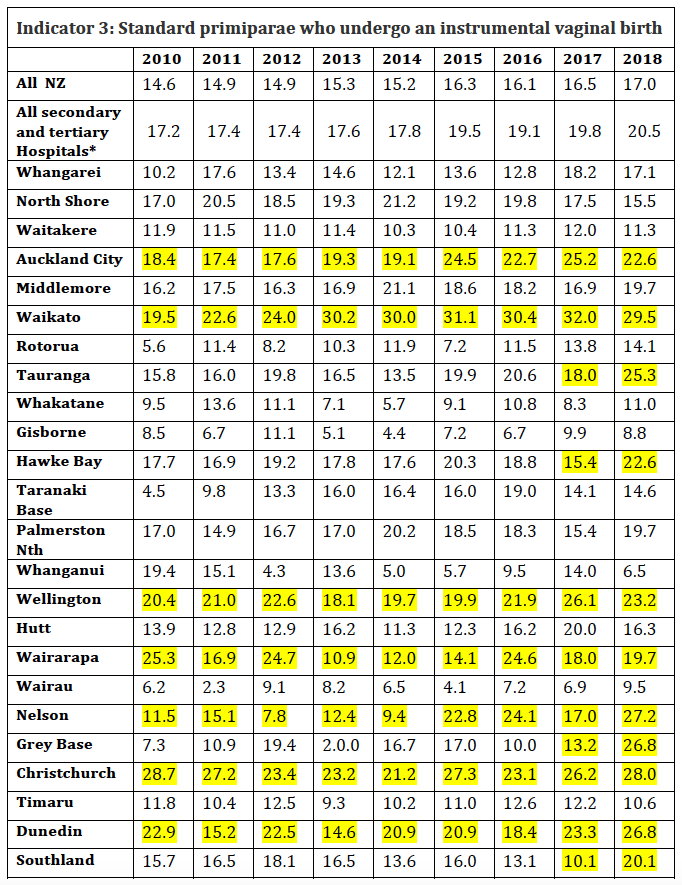

Indicator 3: Standard primiparae who undergo an instrumental vaginal birth. (i.e. vacuum/ventouse and forceps assisted births).

“The use of instruments is associated with both short-term and long-term complications for the mother and the baby, some of which can be serious.” (New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators: Background Document pg9).

As with the c-section rates in the table above, the denominator for this indicator includes all women classified as “standard primiparae” i.e. those who had a c-section are also included. If the rates were calculated on only those standard primparae who gave birth vaginally, the instrumental birth rates would be even higher! Once again, the percentages in the row “all secondary and tertiary facilities is the more accurate percentages because forceps and ventouse assistance are not available in primary birthing facilities.

Why are the MoH and the DHBs not demanding review and changes in practice when the assisted birth rate in our hospitals has risen to one in five for low/no risk women?

Surely there needs to be an investigation, when some smaller facilities like Gisborne, Whanganui & Wairau are able to maintain forceps and ventouse assisted birth rates for standard primiparae below 10%, but facilities like Dunedin, Christchurch, Waikato and Tauranga Hospitals have a culture that results in 2-3x as many of these women and their healthy full term babies being exposed to the risks associated with instrumentally assisted birth? Is anyone interested in finding out why Southland Hospital’s rate of assisted birth doubled from 2017 to 2018?

(Image www.snaplifephotography.com)

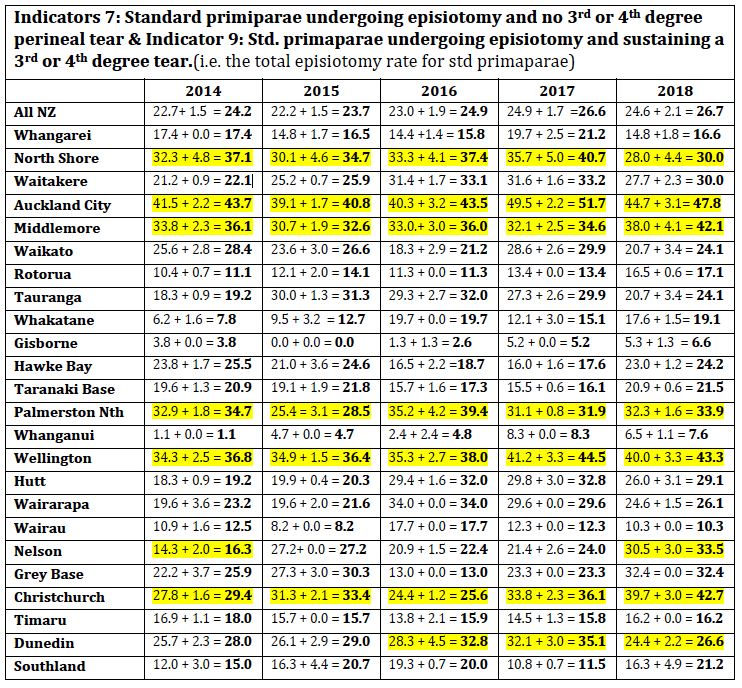

Indicators 7 & 9: Standard primiparae undergoing episiotomy

“Perineal trauma remains one of the most common complications of childbirth and is thought to affect between 60 percent and 85 percent of women who give birth vaginally (WHA 2007). Reasons for perineal trauma are varied, and may reflect either maternal, neonatal or clinical management issues. Perineal damage can cause women pain and longer-term morbidity. The aim of these indicators is to encourage review and practice improvement to reduce trauma and its associated maternal morbidity. Reduced perineal trauma is expected to improve maternal satisfaction and mother−infant bonding by reducing maternal pain and discomfort.” (New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators: Background Document pg11).

In the table below, we have added Indicator 7: Standard primiparae undergoing episiotomy and no 3rd- or 4th-degree perineal tear (first number) and Indicator 9: Standard primiparae undergoing episiotomy and sustaining a 3rd- or 4th-degree perineal tear (second number), to give the total rate of episiotomy (bold number) for this group of low/no risk women birthing their first baby.

The high rate of episiotomy amongst low/no risk women results in further insult and injury to this group of women. Why does the MoH accept that in addition to an increase in surgical births, the rate of episiotomy for healthy women with a full term baby continues to climb to higher than 20– 30% in some of our hospitals. Why do our health authorities and women accept this? Are women informed that if they birth at home they have an 86.3% (2018) chance of having an intact perineum and that this drops to 54.9% (2018) if they birth in a primary unit and to a distressing 17.7% if they birth in a secondary or tertiary hospital? Surely the MoH should investigate why it is that hospitals like Gisborne & Whanganui are able to sustain an episiotomy rate of less than 10% for this group of women (and what changed at Whanganui that resulted in a reduction in episiotomy rates between 2010 and 2018) when in just about every other hospital the rate of episiotomy has continued to rise?

The statistics for Standard primiparae sustaining a 3rd or 4th-degree perineal tear and no episiotomy (Indicator 8) have remained fairly consistent in most hospitals and between 4.0 – 4.5% nationally since 2010. Prevention of serious tears is sometimes given as a justification for episiotomy, however these statistics show that the increasing rate of episiotomy is NOT reducing the rate of serious tears in most of our hospitals,

Women have been asking for some time now for pelvic physiotherapy to be subsidized and accessible for all birthing women – these statistics show that this addition to our maternity services is urgently required. Why is it that “health” system continues to fund unnecessary interventions but will not fund those services that women identify as being needed?

Conclusion

It is tantamount to abuse that so many healthy first time mothers are having their bodies surgically cut i.e. episiotomy or c-section, when birthing their babies and that women, our maternity funders and our maternity providers seem to be accepting of these non-evidence-based outcomes. The statistics in this report show clearly that it is the culture of the management of birth in most of our maternity/obstetric hospitals that is driving these statistics not a physiological need – what happened to, “First, do no harm.”?

These statistics show that the majority of our Level 2 & 3 maternity hospitals are not able to provide safe care for no/low risk women.

MSCC demands that our MoH and DHBs urgently fund and provide accessible primary birthing facilities for all low risk mothers and prohibit secondary/tertiary hospitals from accepting bookings from healthy women who have no risk factorsimmediately, if, or as soon as there is, accessible primary facility capacity.

In response, our maternity facility funders and providers will defend a woman’s right to choose place of birth, and unfortunately, the majority of women do currently choose to birth in a Level 2 or 3 hospital. However this defence of women’s choice ignores the fact that our DHBs have no qualms about denying access to a primary birthing facility. Most DHB’s deny access to women in their birthing population. Many women are denied access because their DHB does not provide accessible Primary Birthing Units (PBU). Others are denied access to Primary Birthing facilities for blanket reasons such as: age over x years old; high BMI; gestational diabetes positive regardless of success with blood glucose management; previous c-section etc etc. Despite claims that our maternity services are “woman-centred”, these prohibitions are enforced without any individual assessment or consultation with the woman and her LMC.

In spite of the fact that international maternal health authorities have been reporting concern about and formulating recommendations to reduce, the inappropriate use of technology in childbirth for over 35 years, developed countries like AotearoaNZ now have two generations of birthing women and care providers who have bought into a culture of fear of birth, and acceptance of high intervention rates. Many women choose hospital birth “just in case” and as the statistics in NZ Maternity Clinical Indicators Reports show, this becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy – our obstetric providers are intervening, not only when evidence-supported interventions are required but, “just in case”.

[1] Ministry of Health. 2020. New Zealand Maternity Clinical Indicators: background document. Wellington: Ministry of Health. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-maternity-clinical-indicators-2018

Birth Time – the documentary

In March MSCC hosted a number of screenings of this important Australian documentary that examines the culture of birth. Three Australian women, a mother, a doula and birth photographer and an independent midwife joined forces to try to discover why it is that nearly one and three Australian women comes out of her birth experience feeling traumatised. The result of their research and interviews is the documentary Birth Time.

Maternity care provision throughout the world, particularly in what we refer to as “developed” countries or developed regions within poorer countries, is the result of nearly 400 years worth of medical intervention into women’s maternity experiences. Maternity care in countries like Australia and NZ is now highly medicalised and driven by a culture of fear. We have become focused on what could go wrong rather than, what usually goes right, with childbirth.

Pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding are species survival behaviours. Somewhere around 7,500 and 10,000 generations of humans have existed thanks to a pretty perfect genetic blueprint for procreation, birth and nurture. Obstetrics, the most powerful maternity sector group, was founded on the premise that the actions of men are able to improve the genetic imprint of childbearing, and on occasion this is definitely the case. Obstetrics has convinced women that the quality of their maternity experience (including any harm to their, physical, psychological, emotional or spiritual health), is secondary to the “delivery” of a live baby. Women have lost connection to and trust in, the most transformative, powerful and primal rite of passage that most of us will ever experience.

This documentary interviews women and maternity care providers and researchers who express their distress and concerns. It also shows excerpts from healing physiological labours and births. It conveys messages that all mothers/parents to be need to see and hear before making their birthing choices.

Several interviewees state that access to midwifery continuity of care would improve women’s experience of maternity and reduce unnecessary intervention. Women in AotearoaNZ have had access to midwifery continuity of care since 1990 and the majority of birthing women in AotearoaNZ receive care from a Lead Maternity Carer (LMC) midwife (60.7% in 2003 and 86.9% in 2017)** . NZ Women do report high levels of satisfaction with the care they receive from their midwives, but our medical intervention statistics are as high as anywhere in the world and midwives are leaving the profession in droves, causing a chronic shortage. Our world leading maternity system is in jeopardy – we are in danger of losing the gains we made back in the 1990s. Women have again become increasingly passive and fearful “consumers” of maternity services and have acquiesced to increasing numbers and rates of medical interventions. This documentary shows that these intervention rates are not leading to generally better outcomes for mother and baby. Developed countries like Australia and NZ, have a postnatal depression epidemic and for years now, suicide has been the leading cause of maternal death in both countries. The personal, societal and financial costs of our maternity service outcomes tell us that it is BIRTH TIME – time for women to take back control of their inherent ability to give birth; to demand that maternity service providers from Government level down provide services that; meet our stated needs; involve only evidence based interventions; are universally available and these are adequately funded.

MSCC continues to encourage women to claim their birth rights and their legal rights during their maternity experiences. It is time to transform the culture surrounding maternity and our maternity system and this documentary is an effective way of conveying these important messages.

MSCC and other individuals and organisations continue to look for opportunities to host screenings of this important documentary in hope that a critical mass of women, whanau and maternity care providers will be inspired, energised and challenged by the beauty, courage, power and knowledge shared in this documentary and work to change their beliefs about, and the culture of, birth in both countries.

Our screenings were well attended by midwives and student midwives (thank you all) – we hope that they will recommend this documentary to all their clients.

** Ministry of Health. 2019. Report on Maternity 2017;p37. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Book Review: Mamas in Lockdown – Personal stories of becoming a parent during Covid-19 lockdown in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Denise Ives is a breastfeeding counsellor who continued to support families, during the level 3 & 4 lockdown period and heard first-hand of their feelings of isolation and lack of support. She felt that giving these parents the opportunity to write down their experiences of maternity care during the 6 weeks of the Levels 4 and 3 “lockdowns” might assist some to process and move on from what was, for many, a bewildering, anxious and lonely time – very different from the joyous anticipation and celebration that most had envisioned.

Nearly 80 stories (mostly women’s) are shared in this book. They are mainly stories of resilience in the face of changes over which the women/couples/whanau had no control. What is striking is the diversity of background and circumstances in individual women’s/whanau experience of maternity in AotearoaNZ. Many women were already coping with major life changes and some with considerable trauma before the lockdown restrictions were imposed. Inequities of access to services were occurring prior to lockdown and the absence of a national maternity strategy during the lockdown, increased and exacerbated these.

Some women did change their birth plan to a home birth so that there would be no separations in their families. For others, the high levels of antenatal surveillance and monitoring that have become such a normal part of women’s pregnancy experience, contributed hugely to anxiety and loneliness, as women were required to attend for scans and tests without the support and comfort of their spouse/partner/midwife etc. Too many mothers and babies ended up having emergency births or major procedures alone.

Many fathers/partners were prevented from being present during key maternity consultations and were not allowed to provide in person comfort and support during investigative procedures, after difficult births, or when babies needed special care or surgery.

Women reported choosing or being required to leave hospital within hours of giving birth – regardless of whether they had birthed vaginally or by c-section. It seems like a miracle that there were no tragedies arising from these early discharge policies, although some did result in medical complications. Postnatal care for many women during Level 4 was sparse and cursory and this led to many mother:baby pairs experiencing problems with breastfeeding. Different facilities and DHBs classed different procedures as “essential” or not. Lactation consultant services and tongue tie remediation assessment and services were mostly not considered essential. One woman, desperate for breastfeeding help wrote to the PM to request that Lactation Consultants be considered “essential” workers. (Given that supermarkets were allowed to operate to ensure that our population did not starve one would have thought that the same care could have been extended to newborn babies.)

Many writers talked about prolonged bouts of anxiety and crying; many expressed sadness at missing the support and involvement of the wider whanau, but many (particularly first time parents), when they had adjusted to their enforced isolation, enjoyed the quiet, uninterrupted,family bonding during the weeks of lockdown.

These stories are a testament to the resilience of women and their whanau and the dedication of many midwives, individuals and organisations that recognised the needs of mothers, babies and their whanau and continued to provide innovative and safe support during “the lockdown”.