WELCOME, TENA KOUTOU KATOA, KIA ORANA, TALOFA LAVA, MALO LELEI, FAKAALOFA ATU.

Welcome to the July 2020 issue of the MSCC’s Newsletter

Maternity Services Consumer Council (MSCC) Turns 30!

In April, in the middle of “Alert Level 4 Lockdown”, the MSCC turned 30! MSCC started its life as an umbrella group representing the over 80 organisations that had an interest in maternity care provision in AotearoaNZ. Given that only a handful of our original member organisations still exist, it is quite something that MSCC is still active. In our second year of existence, MSCC was contracted by the Auckland Regional Health Authority to consult with our member groups and compose a list of consumer identified, Maternity Clinical Indicators. MSCC was unsurprised by the fact that women, regardless of the focus of the groups they belonged to or their ethnicity, identified continuity of maternity care as a top quality indicator in maternity service provision. It was obvious that the only professional group able to provide continuity of maternity care was, and is, midwifery.

Continuity of midwifery care was made possible by the passage of the Nurses Amendment Act in September 1990, a legislative change that gave midwives, independent practitioner status. Several of the MSCC’s member groups had worked actively to get the Nurses Amendment Bill introduced into Parliament and passed into law.

MSCC also supported member groups who were promoting the need for legislation that would give health care consumers the legal right (and responsibility) to make informed choices about their health care, medical procedures and treatments, and use of pharmaceutical drugs.

By the time the Health and Disability Commissioner Act (1994) and the Health and Disability (Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights) Regulations (1996) had passed into legislation, MSCC had already published the consumer resource, “Choices for Childbirth” to inform women of their maternity options and encourage them to make informed choices during their maternity experience.

During our first 20 years, MSCC was regularly approached to provide an informed consumer voice in the planning, provision and evaluation of maternity care. As more interventions in maternity care became commonplace or even “routine”(!), MSCC continued to publish evidence-based, consumer focused, resources in an effort to inform and encourage women, to have confidence in their inherent ability to grow, birth and nurture their babies and to participate actively in, and make informed choices about, their maternity care.

Although MSCC continues to be supported by a large number of consumers and midwives living throughout AotearoaNZ, it feels as though maternity service provision and outcomes have actually slipped backwards during this organisation’s lifetime.

MSCC has consistently promoted and supported the benefits of midwifery continuity of care for all pregnant women. In 2003, 60.7% of pregnant women registered with an LMC midwife, by 2017 this had risen to 86.9%. In the past 20 years, the workload of LMC midwives has increased dramatically. More and more consultation time is spent juggling the informed consent process and all the administration associated with the increasing medicalization of pregnancy and birth, with their core work of educating, supporting and monitoring the progress of women and their babies, through the physical and non-physical transitions of childbearing.

MSCC has relentlessly promoted the benefits of physiological, pregnancy, labour and birth and breastfeeding and during the past 30 years, the body of evidence supporting this stance has grown enormously. In spite of the evidence, it seems that as a culture, we have more confidence in medical intervention than in the normal physiology of human reproduction that ensured the survival of the species for nearly 300,000 years before the advent of modern medicine.

MSCC continues to promote the rights and responsibilities of childbearing women and their maternity care providers. MSCC continues to monitor maternity service provision and demand that women receive respectful maternity care that supports the normal physiology of human reproduction alongside the health and wellbeing of women, their babies and whanau. We continue to provide information and support to maternity consumers, encouraging them to trust their bodies and birth and to make informed choices about their care. We continue to challenge the Ministry of Health and District Health Boards to provide accessible primary birthing options. We continue to educate about the individualised and evidence-based use of medical interventions. We continue to advocate for access to midwifery continuity of care for all women who choose this option, and for fair and equitable remuneration for LMC and hospital based midwives.

MSCC looks forward to a time when we can say, “our work is done”, however, it’s looking like the work of the MSCC will be needed for some years to come!

PS: There’s still a lot to do!

MSCC welcomes new supporters and Steering Group members. If you are interested in supporting the work of the MSCC we’d love to hear from you. Drop us a line to [email protected]

Birth During the Pandemic

Many commentators have stated that the national and international spread and response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been “a great equalizer”, and that “we are all in this together”. These statements ignore the hugely differing levels of impact that the pandemic and the pandemic response has had on for example, essential workers, the homeless, those who have lost and will lose their jobs, the chronically ill, those who were awaiting surgeries, diagnostic procedures and medical interventions necessary for prolonging or saving their lives, those living alone, the approximately 6000 people who died (from other causes) and their families…the list could go on. It certainly includes the approximately 10,000 women/whanau who birthed in NZ under the restrictions of Alert Levels 4, 3 & 2.

SARS-CoV-2 will not be the last novel virus to spread across the globe. Human activities continue to increase the risk of cross species transfer of viruses. Population expansion and exploitation of the world’s natural resources pushes humans into the habitats of other species with whom we have previously had minimal contact; medical science (and sadly, the science of chemical weaponry), experiments with viruses extracted from a variety of species (including bats); and the transportation of viral material from lab to lab around the globe. All these human activities increase the risk of accidental release and cross contamination both within and outside the laboratory environment.

As the threat of Covid-19 diminishes, it is time to put in place protocols for protective measures that will not be so costly to the wellbeing of so many, when the next novel virus comes our way.

The births of approximately 5,000 babies every month in AotearoaNZ was a totally knowable phenomenon that was not going to be postponed because as a nation, we agreed to self-isolate at home. MSCC believes that it is essential that we re-organize the way that we provide and consume maternity services to prevent the trauma and grief that many mothers, their babies, partners and families have experienced during the past few months.

Many hundreds of women and whanau will grieve for what they missed out on including; the women who endured induction of labour alone; the women who spent the first few days after giving birth alone in hospital isolated from the loving presence of their partners and whanau; the women who birthed without their partners because there was no one else in their homes to look after their other children; the women who returned home within hours of birthing (often after c-section surgery) and who had to care for their newborn and often, their other children as well, without the assistance of whanau and friends; the new mothers whose partners are essential workers and had to keep working, leaving mother and newborn home alone (sometimes with other children) in the early postnatal period.

Although it is easy to trivialize the transition rituals that have become part of the maternity experience for many women in our country, large numbers of particularly, first time mothers, missed out on: the farewell from work; the baby shower; the late pregnancy photoshoot; etc. These rituals help many women to make the huge transition from independent (working) woman to new mother, providing opportunities to celebrate, signal and embrace the transition into their new identity, with family, friends and colleagues, and can assist women to embed their new persona and role thereby supporting a healthier postpartum experience.

Primary Birthing Options – A Healthy Pandemic Response

Fortunately, in many parts of the country, women had access to an obvious solution to the threat of isolation and the virus during labour, birth and the postnatal period – primary birthing options.

Many women with the support of their midwives, found the courage and confidence to birth at home so that their family unit could stay together, or to birth in a Primary Birthing Unit that allowed partners to “room-in” during the postnatal period.

MSCC has been educating, encouraging and lobbying for decades, for primary birthing options to be the norm for healthy mothers and babies in AotearoaNZ. The threat of future epidemics, makes it essential that our Ministry of Health and District Health Boards take the lead in re-establishing a culture of primary birthing. We need to keep mothers and babies out of hospitals: away from the possibility of inadvertently contracting the latest circulating microbial illness and; away from the institutionalised fear and mistrust, of women’s bodies and the normal childbearing process, that has resulted in the overuse of medical interventions.

There are already compelling health and financial reasons to promote Primary Birthing, the Covid-19 experience has added another reason for a re-structuring of our maternity services and making primary birthing options the norm – one of the most dangerous places for a well woman and her newborn to be during any epidemic, is in a hospital.

Our maternity facilities need to put in place processes that meet the needs of the women/whanau who use them, as well as protecting them from the risks associated with circulating viruses without separating them from their loved ones. The Covid-19 experience has reinforced the need for:-

- Well-women to be encouraged and supported to stay out of hospital.

- All DHBs must fund and provide accessible Primary Birthing Units for women throughout their catchments.

- All Primary Birthing Units to be freestanding – i.e. must not share common entrances or facilities if they are on a hospital site to reduce the risk of contact with and cross infection from patients and staff carrying the circulating pandemic organism.

- All postnatal rooms must be single rooms with an ensuite bathroom to allow partners to sleepover and siblings to visit, during the crucial, early postnatal, family bonding period.

- Neonatal Intensive Care Units must be organised and have protocols in place, that will allow parents to continue to be able to spend time and care for their sick or preterm babies, even during a pandemic.

- Breastfeeding must be supported unless there is solid evidence of mother to baby transmission.

- DHBs must establish and fund breastmilk banks so that mothers who are unable to breastfeed during a pandemic (if evidence shows viral transmission via breastmilk) have the option of feeding their babies human milk.

- Maternity facilities must have consumer input into the design of their pandemic protocols.

Pandemic or not, isolating either parent from their newborn baby/babies, is not an option unless that parent has returned test results indicating that they are infected. Isolating parents from each other during the maternity experience is also not acceptable. Preventing a mother from providing breastmilk for her baby, unless there is evidence that this is dangerous, is not tolerable. The easy solution, as many families figured out during April and May, is to birth at home or in a Primary Birthing Unit – let’s make this the norm.

Midwives & Covid-19

MSCC would like to thank and acknowledge LMC and Core midwives for the additional care and comfort that they provided during “Lockdown” to women and babies who required midwifery care. The reports from women, of the midwifery care they received both in the community and in facilities, have been overwhelmingly positive.

LMC midwives continued to provide essential care for mothers and babies, in their consulting rooms, in womens’ homes and in various maternity facilities. Many LMC midwives had to provide, extra and more complex care than usual, to mothers and babies who discharged from hospital early, often within hours of undergoing a caesarean surgery.

Among midwives, as within the wider community, individuals experienced varying levels of fear and anxiety about the possibility of catching and/or transmitting Covid-19. LMC midwives carried the additional burden of concern about unwittingly transmitting the virus between the homes they were visiting, into or from the hospitals and birthing units in which they attended births and carrying it home to their own family members.

Core midwives faced similar concerns about inadvertent transmission yet women report that many spent extra time with them, especially postnatally, to compensate for the absence of partners and whanau.

Pandemic, lock-down and postnatal depression

A second important reason why we must come up with a positive, proactive plan for a maternity response to an epidemic/pandemic is reducing the harms of postnatal depression.

Research suggests that between 13-18% of new mothers in AotearoaNZ experience postnatal depression (PND). Giving birth during the Covid-19 pandemic and the national response to this virus, would certainly have increased the numbers of new parents experiencing the feelings of fear, sadness, overwhelm, detachment and isolation commonly associated with postnatal depression.

Some situations that are considered risk factors for developing PND are:

- previous mental health problems

- lack of support

- experience of abuse

- low self-esteem

- poverty and poor living conditions

- major life events.[1]

It is obvious nearly all of these factors would have been amplified by the pandemic and the subsequent “lock-down” leading to a higher percentage of women who birthed during the pandemic response, being exposed to both, the risk factors for and the emotional responses associated with, postnatal depression. Feelings of intense emotion, anxiety and exhaustion are normal in the days after birth. These feelings are likely to have been compounded by the climate of fear and uncertainty surrounding the spread of Covid-19 and the physical distancing rules that left many new mothers unable to receive physical, practical and emotional support from their partners, family/whanau and friends.

We may have eliminated the virus but we may also have increased the burden of PND and its longer term effects on mothers and their babies. PND negatively affects interactions between mother and child and consequently the emotional, social and cognitive development of the child can suffer.[2]

Given that the early postpartum period is one of the most important stages for infant development, and that the negative effects on child development have been shown to be directly proportionate to the duration and severity of the maternal mood disorder, it is essential maternal depression is addressed effectively to ensure the happiest and healthiest outcomes for mothers and children. MSCC urges the Government to include funding and support in their post-covid-19 recovery plan for the agencies and therapies that assist mothers and fathers to recover from postnatal depression.

COVID-19, Pregnancy, Birth and Breastfeeding

There is a chance that as we resume usual human interactions that cases of Covid-19 will recur. Research into the SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19,the disease that it can cause, is just beginning to emerge and the findings from emerging international research, shows that women of childbearing age and their children(<1% of cases

have occurred in children) are not amongst the demographic most seriously affected – the average age of people needing hospitalization is 49 – 56 years old (30 – 50% of whom had some underlying illness), the majority of whom are men (54-73%)[3]. Covid-19 infected pregnant women appear to be no more seriously affected than are matched non-pregnant women. In addition, there have, so far, been few confirmed instances of transmission from COVID-19 infected mothers to their babies, neither have viral isolates been found in the amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swabs or breastmilk of infected women.[4]

There is currently no evidence of maternal to infant transmission, regardless of mode of birth, and no evidence of transmission via breastmilk.[5]

A recently published piece of research from Spain[6] that reviewed the clinical data from 60 pregnant women diagnosed with Covid-19, showed that 25% remained asymptomatic, 70% developed mild or moderate symptoms and 5% experienced severe to critical symptoms. None of the women experienced renal or cardiac failures and none died. 78% of these women birthed their babies vaginally. All newborn babies were tested in the first 2 hours after being born, and none tested positive. None of the breastfed babies subsequently tested positive for Covid-19.

Samples of placental tissue from 6 women were also analyzed and tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

UNICEF advice about breastfeeding during the pandemic

MSCC received some reports of mothers who coughed, sneezed or had an elevated temperature, being separated from their babies, and their babies being given infant milk formula, till the mother returned a negative test for COVID-19. We also heard of mothers (who had already been discharged home) being prevented from visiting and breastfeeding their babies in NICU/SCBU. There was and is no evidence of the necessity for separating mothers and babies or restricting breastfeeding.

“Should I breastfeed if I have or suspect I have COVID-19?

Yes, continue breastfeeding with appropriate precautions. These include wearing a mask if available, washing your hands with soap and water or with an alcohol-based hand rub before and after touching your baby, and routinely cleaning and disinfecting surfaces you have touched. Your chest only needs to be washed if you have just coughed on it. Otherwise, your breast does not need to be washed before every feeding.

Can I pass COVID-19 to my baby by breastfeeding?

To date, the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus through breastmilk and breastfeeding has not been detected, though researchers are continuing to test breastmilk.

Should I breastfeed if my child is sick?

Continue to breastfeed your child if she becomes ill. Whether your little one contracts COVID-19 or another illness, it is important to continue nourishing her with breastmilk. Breastfeeding boosts your baby’s immune system, and your antibodies are passed to her through breastmilk, helping her to fight infections.”

UNICEF, Breastfeeding safely during the COVID-19 pandemic, 28 May 2020,

https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/breastfeeding-safely-during-covid-19-pandemic

My Vaginal Breech Birth, by Jessica How

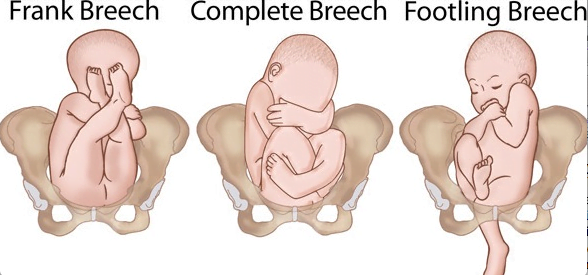

I had the most amazing pregnancy, I was extremely active and had no problems or concerns what-so-ever. At 32 weeks I had a growth scan which showed baby was still in a frank breech position, as she had been my whole pregnancy. I was told that only 1-2% of babies stay breech at full term, but being a breech baby myself I just knew that she wasn’t going to turn so I started investigating my options of having a natural vaginal birth with a frank breech baby.

Everything I read pointed to a c-section as being the “best” and “safest” way to bring my girl into the world, but I was unconvinced and a c-section was NOT an option for me. (Nothing against those that have them, it is definitely not the easy way out.) You see, i have 2 highly energetic dogs that need to be run twice a day which meant there was no way I could sit around for weeks recovering from surgery. Mostly though, I felt I would be ripped off if I didn’t get to experience a vaginal birth and allow my body to bring my baby into the world. I was determined to birth naturally. I researched every piece of information I could find on breech birth and was adamant I could do it.

I expressed my birth plan to my midwife and as she had no experience with vaginal breech birth, she was worried about the numerous things that could go wrong. She did a lot of behind the scenes research and emailed around to see who would support me and what we needed to do. She was nervous but managed to hide this well as she never gave me any reason to be. (I found out after giving birth that she was absolutely petrified but also really excited.) She was 100% supportive of my decision, although she couldn’t be clinically in charge as it was a specialized birth.

Next step was to get the support of the obstetricians in Rotorua hospital. After a few emails and a lot of ‘begging’ from my midwife they agreed to meet with me to discuss my options. I was lucky enough to come across one that would “allow” me to give it a go BUT it all depended on who was on call at the time I went into labor – apparently most of the obstetricians were not supportive or experienced with vaginal breech births. Her support came with a number of “conditions”…

* I was only allowed to go to 40 weeks before a c-section would have to be done.

* I was allowed a trial of Labor. If I was progressing well (1cm per hour) then I was allowed to continue.

* I had to be strapped into the fetal heart monitor and on a bed during labor.

* I had to give birth with my legs in stirrups

* When it came time to push, if I had been in labor too long and was fatigued then I would need an emergency c-section

* I had to make the journey from my home (Taupo) to Rotorua as soon as labour began so I could be monitored closely.

* I wasn’t allowed any drugs other than gas and air.

I can’t say I was happy with any of their conditions and I left the appointment feeling overwhelmed and slightly confused. Why did it have to be so hard, it was just a birth?! I was now more determined than ever to have it my way and let my body do what it was made to do.

After returning home, I had an appointment with my midwife and we discussed what the obstetrician had said and decided on our own plan of action that included more of what I wanted – I would labour in Taupo Maternity Unit for as long as possible, as long as the fetal heart rate was good and I would make the journey to Rotorua Hospital as late as possible. This would give my body more time to progress without intervention.

I joked with my midwife that now we had a plan my baby could come right now. I was 38.2 weeks and ready to roll. I felt a weight lift off my shoulders with her reassurance and back-up. Being a first-time mum I had no idea what I was in for, but staying upright and mobile and not confined to a bed was what I wanted. I 100% put my trust and faith in my midwife as she knows what’s best right?

Fast forward a few hours to that night and me waddling to the toilet for the 3rd time since going to bed. I felt warm liquid running down my legs but not thinking anything of it, went back to bed. When it happened again though, I realised what had happened. I texted my midwife to tell her my waters had broken but no contractions had started and she advised me to put a towel underneath me in bed and try get some sleep, ready for action in the morning.

Well that didn’t happen! Contractions started hard and fast within 15 minutes. I walked laps of the house and played with my dogs for 3 hours then phoned my midwife to tell her that my contractions were getting strong and close together and that I could no longer sit down. She decided we should meet at the Maternity Unit and do some checks, so off we went. On arrival, my midwife examined me, I was 5cm dilated and baby’s heartbeat was good and strong.

I was so hot, I laboured outside in the cool air. In between checks on me on my baby, my midwife was in contact with Rotorua and luck was on our side. The obstetrician I had just seen that day was on duty and ready for us BUT her boss was also on and not keen at all. I was gutted but was not going to give up that easily. Hearing that news, we decided to stay in Taupo as long as possible. The next 2 hours flew by and when my midwife examined me, I was 8cm dilated. A bit of panic must have set in for my midwife who ordered an ambulance to transfer me to Rotorua as it was looking highly possible I might deliver on the side of the road before we got there!

My midwife’s amazing wingwoman arrived as a confidence booster and support for both of us. It was decided that this back-up midwife would travel in the ambulance with me as she had previous experience with breech birth.

Nerves were setting in as ‘the moment of truth’ drew closer. After what felt like a half-day trip, we made it to Rotorua Hospital where I was greeted by a room full of 8 doctors and nurses. It was at about this time that I went into my own zone as I tried to blank out all these people. I remember being told to get on the bed and get the monitor on; being asked a whole heap of questions; and being asked to sign forms to say, if “shit hit the fan”, the hospital had explained the risks and wouldn’t be held responsible. My midwife asked them to leave when I just stared at them blankly. The head obstetrician kept telling my midwife that if I didn’t comply with their conditions, I would have to have a c-section.

My lovely midwife calmly talked to me and although I didn’t want to, I managed to get on the bed and she held the monitor on abdomen rather that strapping it on me. The hospital staff weren’t very impressed, but that’s the best they were getting.

I got to 10cm dilated and was ready to push. The head obstetrician came back and said if the baby wasn’t out in 45 minutes I would need to go to theatre, as it was too risky to continue – Not what I wanted to hear! – but this was him covering his ass I guess. He also reminded all 10 people who were now in the room that they were to remain hands off and not to touch the baby or provide any help as it came out.

As I pushed and felt the feet ping down and as her shoulders were about to emerge she rotated herself and one by one her arms flipped out. She now hung by her head and I asked someone to support her little body but they all said they weren’t allowed, one more push and my midwife helped slightly to deliver the head. I pushed for 20mins and out came my precious little girl. She was just perfect, all she needed was a wee bit of oxygen.

I was ecstatic, I had done it. Nothing went bad, no interventions were needed and it was all drug free – ten hours from start to finish.

I then got a long apology from the head obstetrician, who admitted that I proved him wrong and that it was the most straight-forward, text book breech birth he had ever seen. He said he was just very scared in case the outcome wasn’t good and that he could have prevented it.

I got the birth I wished for and despite all the ‘protocols’ and ‘conditions’ I had been directed to follow, I was over the moon.

So what now… why not make breech birth a variation of normal instead of being hardly talked about and never performed? Maybe maternity professionals need more training in breech birth as it seems to be a forgotten thing. Slowly as time has gone it has slipped into the too hard and unsafe basket and become a forgotten way to birth. Birth is natural and it should be allowed to happen how the labouring woman wants it to, without battles and interventions that are unnecessary.

Breech Birth in AotearoaNZ

MSCC is delighted that Jessica agreed to share her vaginal breech birth story. Even though her daughter is now 4 years old, the few women who are informed, intuitive and confident enough to request support for a vaginal breech birth each year in AotearoaNZ, mostly still face the same scare tactics and non-evidence based management that Jessica did four years ago.

This birth story is such a good example of maternal informed choice and decision-making and a functional and trusting partnership between a woman and her midwife. Jessica’s desire to birth her baby vaginally and her intuitive “knowing” that this was safe and “right” for herself and her baby, even after her own research and the information provided by the local obstetrician focused on the risks associated with this choice, is inspiring. We commend Jessica’s midwife for the background work that she did (researching into supporting physiological vaginal breech birth and finding a second midwife who had some breech birth experience), to ensure that she could safely facilitate Jessica’s birthplan, and for practising partnership, respect and support for her client’s innate ability to make safe choices for herself and her baby.

There is a growing body of research supporting vaginal birth for women whose babies are either in a “Frank Breech” of “Full Breech” position. However, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) Guideline for, “The management of breech presentation at term”, appears neither to have incorporated this research nor to have a thorough understanding of health care consumers’ legal rights to make informed choices about their care. In many instances, women, like Jessica, are informed of what the medical professional thinks is the best course of action and expected to consent to whatever is being recommended. This Guideline was last updated in July 2016 and was flagged for review in July 2019, however MSCC could not find any evidence of a 2019 version.

It is significant that the language in RANZCOG Guideline renders any woman whose baby is in a breech position, a passive partner in the decision-making regarding mode of birth. Their recommendations re “individualizing” management refer only to the individual obstetrician’s experience and individual institution’s facilities, no mention of supporting the stated choices of individual women and no statements of confidence in the physiological process of birth. According to this guideline, it is only possible for a breech baby to be born vaginally if the birth is managed by obstetric manoeuvres. The whole guideline appears to be based on the assumption that a vaginal breech birth might be achieved for obstetrically selected women, who must be completely passive while an “experienced” obstetrician actively manages the birth. (As per the conditions imposed on Jessica.).

Recommendation 5 (page 4)

“Where there is maternal preference for vaginal birth, the woman should be counseled about the risks and benefits of planned vaginal breech delivery in the intended location.”

Recommendation 7 (page 4)

“Planned vaginal breech delivery must take place in a facility where appropriate experience and infrastructure are available:

- Continuous fetal heart monitoring in labour.

- Immediate availability of caesarean facilities.

- Availability of a suitably experienced obstetrician to manage the delivery, with arrangement in place to manage shift changes and fatigue arrangements.”

“Almost 90 per cent of fetuses presenting breech at term are now delivered by caesarean section.”(page 8) This statistic does not support “Individualised Management” but it does explain why very few maternity professionals have witnessed or supported obstetrically managed breech births let alone, physiological breech births.

The introduction to the guideline does discuss some potential risks of planned c-section for breech presentation stating, “The benefits of Caesarean section reducing newborn morbidity must be balanced against the immediate and longer-term risks of Caesarean delivery. The downstream risks relating to future births include the potential for scar rupture in labour, the surgical risks of repeat caesarean section and placenta accreta.”(page 5) The “immediate” risks for mother and baby are not defined, e.g. excessive blood loss, infection (and exposure to antibiotics), alteration of the newborn microbiome, post-operative maternal pain, maternal and newborn exposure to pain relieving medication, reduced mobility, increased risk of prematurity requiring newborn intensive care, increased risk of difficulties with establishing breastfeeding etc.

The rationale for the recommendation that breech babies should be delivered by caesarean section is the small increase in neonatal mortality and morbidity when the outcomes for vaginally born breech babies are compared with those for breech babies born by caesarean section. The studies on which this recommendation is based, do not tell us how the mothers and babies laboured and birthed. However, it is likely that the women were in a supine/lithotomy position for second stage of labour. This position often results in slow progress, the need for obstetrical manoeuvres, including forceps, to rotate and extract babies against the force of gravity. All of these interventions add to the risk of morbidity for mothers and morbidity and mortality for babies. Some recent studies, however, provide, good quality evidence about the relative risks of vaginal and caesarean birth for breech babies when the labouring mother is supported to birth in an upright, or all-fours position.

Is vaginal breech delivery associated with higher risk for perinatal death and cerebral palsy compared with vaginal cephalic birth?

A large Norwegian study[7] published in 2017, provided much needed evidence to help mothers, parents and their maternity care providers understand these risks and make informed choices about mode of birth. “The aim of this study was to explore if singletons without congenital malformations born vaginally at term have higher risk for stillbirth, neonatal mortality (NNM) and cerebral palsy (CP) if they are born in breech position compared with cephalic position.” This study compared the birth outcomes of 16,700 breech babies with 503,347 planned vaginal births of vertex presenting (head first). All the babies in the study were singleton; full-term/>37 weeks gestation; with no known congenital anomalies; and were born between 1999 and 2009. “Of the 16 700 women with a fetus in breech 7917 (47%) were planned for vaginal delivery, while 5561 (33%) actually delivered vaginally. The corresponding figures for planned caesarean delivery were 8783 (53%), while 11 139 (67%) actually delivered by caesarean. For women with fetuses in cephalic position, 94% were planned to vaginal delivery while 90% delivered vaginally; 6% were planned to caesarean delivery and 10% delivered by caesarean”

Vaginally born breech babies had a neonatal mortality rate (NNM) of 0.9 per 1000 compared 0.8 per 1000 for breech babies born by c-section and 0.3 per 1000 for vertex presenting vaginally. This study showed that breech presenting babies had an increased risk of NNM, irrespective of mode of birth, compared with vertex presenting babies.

| Neonatal Mortality | |

| Cephalic/Head down babies | Rate per 1000 babies |

| Vaginal birth | 0.3 |

| Caesarean Section | 1.7 |

| Breech Babies | |

| Vaginal Birth | 0.9 |

| Caesarean Section | 0.8 |

| Planned Mode of Birth | |

| Cephalic/Head down babies | |

| Planned Vaginal Birth | 0.4 |

| Planned caesarean section | 1.0 |

| Planned Mode of Birth | |

| Breech Babies | |

| Planned vaginal birth | 1.0 |

| Planned caesarean section | 0.7 |

There was no statistically significant increase in the incidence of cerebral palsy (CP) for breech babies (irrespective of mode of birth) compared with vertex presenting babies.

The authors of this report conclude: “Taking into consideration the very low absolute risk for NNM and CP, the increasing evidence for acute and long-term maternal complications and for later health problems among children following caesarean delivery, our results suggest that vaginal delivery in selected cases may be an option for women with a fetus in breech position…In the discussion with the pregnant mother and her partner regarding choice of delivery mode of a fetus in breech, the relative risk for NNM should be explained but related to the very low absolute risk. Moreover, it may be appropriate to emphasise that adverse outcome probably to a large degree is caused by antenatal acquired insults and that there are potential advantages of vaginal birth over caesarean delivery for long-term health of the child and the mother.”

“Breech delivery in the all fours position: a prospective observational comparative study with classic assistance”

This 2015 study[8] documented outcomes for 41 mothers and babies who had a vaginal birth with babies in a breech presentation and were supported to birth in an “all fours” position. These women were encouraged to adopt the “all fours position” in the pushing stage of labour and were simply observed by the attending midwife and obstetrician, no manual manoeuvres were performed. This position utilised gravity and the weight of the baby’s body to create the traction necessary to birth the babies’ heads – the midwife was ready to “catch” the baby as its head was born, to prevent it from dropping to the bed etc.

The outcomes for the upright breech group were compared with outcomes for 41 women who, during the same time period, gave birth vaginally to breech babies with “classic support” i.e. continuous fetal heart monitoring and mother in the lithotomy position, manual perineal support at “rumping”, recommendation for episiotomy and lifting the baby’s body to assist the birth of its head etc.

All women in the study group gave birth vaginally; 29 women needed no obstetric intervention; a further 8 required some obstetric assistance; the remaining 4 women had to move into the lithotomy position and their babies were delivered with the help of “classic” obstetric manoeuvres. Only 14.6% of women in the “all fours” group experienced injury to the birth canal /perineum including episiotomy, (the most severe of which, occurred in the two women who required routine obstetric assistance using the classic delivery techniques in the supine position), compared with 61% of women in the lithotomy group. Although more of the babies in the “all fours” group experienced some hypoxic stress during labour, this did not result in a statistically significant increase in either lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes or admission into neonatal intensive care. (7 babies in the study group vs 6 in the control group).

Does breech delivery in an upright position instead of on the back improve outcomes and avoid cesareans?

The aim of this retrospective cohort study[9] was to compare the outcomes for three different groups of mothers with a singleton baby in a breech position at term.

1. Vaginal breech birth with the mother in an “upright” position e.g. leaning over the back of the hospital bed on the knees, on all fours, or standing,

2. Vaginal breech birth in which the mother was lying on her back

3. Planned caesarean section for mothers and their singleton babies who were in a breech position at term.

This study looked at the data relating to 750 mothers who birthed their breech babies in a Frankfurt hospital, between 2004 and 2011. 315(42%) of mothers chose to birth by caesarean section. Of the 269 women who birthed their babies vaginally, 229 adopted an upright position and 40 a supine position. Unsurprisingly, the outcomes for the mothers who birthed in an upright position were better than those who lay on their backs and the short term outcomes for these babies were comparable to those born by c-section.

The authors state that, “We compared outcomes of women who were planning a cesarean with those planning a vaginal delivery at the time of admission. In the few cases when no obstetrician experienced in vaginal breech birth was available, the option was no longer offered. These women were put into the planned cesarean group for analysis. Then we compared vaginal births in an upright position with those in the dorsal position. Vaginal births were being done in both the dorsal and newly developing upright position in the first experience and preference. By 2009, essentially all vaginal breech births were being done in the upright position.”

5 years of the study period (2004–2008) on the basis of individual obstetrician

In this study, 435 women planned to birth vaginally. 271 (62.3%) had a successful vaginal birth, including 54.5% of the 288 first time mothers in the vaginal birth group. There were no maternal deaths, but three babies, all of whom had lethal birth defects diagnosed before birth, died. (Interestingly, the mothers of two of these babies still chose to birth vaginally.)

During the first years of the study, when the supine position for planned vaginal births was adopted almost one‐third of the time, the c-section rate was 45.8%. However, during the last 2.5 years of the study period, when nearly all women in the vaginal breech birth group adopted an upright position, the c-section rate fell to 31.1%.

Overall, the length of second stage of labour was 42% shorter when the mother adopted an upright position compared with those in a supine position. The need for obstetric assistance to birth the baby was 95% in the supine group compared with 43.7% in the upright group. There were fewer third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears amongst the mothers in the upright position. (Notably, forceps were not used in any of the vaginal breech deliveries.) 10% of women who birthed vaginally in a supine position and 0.9% who birth in an upright position had an episiotomy. (NZ’s rate of episiotomy for cephalic (head first) vaginal births, is much higher than this?!) The induction of labour rate (recorded only for the last 18 months of the study), was also very low. Of the 142 planned vaginal breech births during this period, only 13.4% were induced, even though, 15 women gave birth between 41weeks, 3 days and 42 weeks, (7 of whom were induced), and 7 women gave birth after 42 weeks (no inductions but one woman opted for an elective c-section). 90% of women who birthed while on their backs had an epidural (low dose, allowing some movement) compared with 64.6% of women who birthed in an upright position.

Newborn injuries and morbidity related to birth mode was low in both the elective c-section and planned vaginal birth groups (0.6% cf 1.4%). There was a more noticeable difference in birth injuries for babies when comparing the upright breech birth and supine breech birth groups (0.9% cf 10%) however, the actual numbers of babies affected (2 and 4 respectively) was tiny. In this hospital, the mothers of small breech presenting babies, <2000gm, or those diagnosed with interuterine growth restriction were advised to birth by c-section. However there was no upper limit for estimated fetal weight and vaginal breech birth. “We argue that the bigger the fetus, the more robust, the abdominal circumference and legs create the required wider opening for the arms and head that follow.” There were no time limits imposed on the rate of progress during the first stage or second stages of labour (another “condition” imposed on Jessica), with the authors stating that “turning and descent is considered more important for decision making in (vaginal breech births)”.

The authors note that, “Half the planned cesareans at the study hospital were at the mothers’ request, suggesting a perception of fear around breech, even in a hospital environment where vaginal breeches are considered safe and common. It is important to point out that the cesarean solution has been driven by research comparing cesarean with women delivering vaginally only in the dorsal position.”

The two studies reported here represent a tiny proportion of the research published during the past 20 years about the benefits and safety of upright birthing positions for full term breech babies. It is time women and their babies were provided with access to information about safe, vaginal breech birth and support for this option, rather than being frightened into elective caesarean surgery or coerced into enduring obstetric “management” of vaginal breech birth that is not evidence based and often results in unnecessary trauma and morbidity for mother and baby.

[1] Hatloy, Inger, Understanding postnatal depression(1994) Mind(National Association for Mental health) retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/get-help/a-z/resource/26/postnatal-depression

[2] (Quevedo et al., 2011).

[3] Rasmussen SA et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019(COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. AmJ ObGyn (2020) 222:5;415-426

[4] Muldoon KM et al. SARS-CoV-2:Is it the newest spark in the TORCH? J Clinical Virology 127(2020)104372 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100135

[5] Muldoon et al. (2020)Op Cit.

[6] Pereira, A et al. Clinical course of Coronavirus Disease-2019(Covid-19) in pregnancy. AOGS(2020): https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13921

[7] Bjellmo S et al. Is vaginal breech delivery associated with higher risk for perinatal death and cerebral palsy compared with vaginal cephalic birth? BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014979. Published 2017 May 4. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014979

[8] Bogner G, et al. Breech delivery in the all fours position: a prospective observational comparative study with classic assistance. J. Perinat. Med. . (2015):43;707–713.

[9] Louwen F et al. Does breech delivery in an upright position instead of on the back improve outcomes and avoid caesareans? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136(2):151-161. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12033