WELCOME, TENA KOUTOU KATOA, KIA ORANA, TALOFA LAVA, MALO LELEI, FAKAALOFA ATU.

Welcome to the March 2020 issue of the MSCC’s Newsletter.

International Year of the Midwife

The World Health Organisation(WHO) has announced, for the first time in it’s history that 2020 will be the International year of the Nurse and Midwife. WHO has designated 2020 the International Year of the Nurse and the Midwife primarily in an effort to address the workforce shortages and the growing diversity of professional challenges faced by these occupational groups. WHO estimates that the world will need 9 million more nurses and midwives if it is to achieve universal health coverage by 2030. WHO is hoping that this year will provide an opportunity to not only celebrate the work of nurses and midwives, but also to advocate for increased investment internationally in the nursing and midwifery workforces.

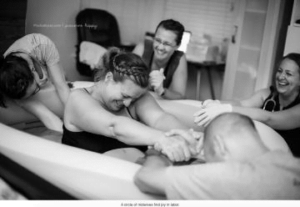

The celebration of the contribution that midwives and nurses make to health and wellbeing of the community will be a little different in AotearoaNZ, because here, unlike in many countries midwifery is an independent and autonomous profession rather than being an adjunct to nursing. In AotearoaNZ, midwives attend the birth of every baby that is born, either as an LMC midwife supporting women to birth at home, in a Primary Birthing Unit (PBU) or in a hospital or, as an hospital/PBU-employed midwife supporting women as part of the midwifery/obstetric team. On average around 168 babies are born each day in AotearoaNZ. Hopefully, the international focus on midwifery this year will be an opportunity to inform our community about midwifery education, skills and scope of practice and to inspire people to either enter midwifery training or return to the practice of midwifery.

MSCC hopes that this year’s focus on midwifery, will lead to; increased awareness and pride in midwives’ expertise in supporting physiological birth; encourage more midwives to support and promote the benefits of primary birthing; and inspire more women to claim their inherent birthing abilities and choose primary birthing options.

In this edition we look at the evidence that supports primary birthing options and the state of primary birthing units in several parts of the country.

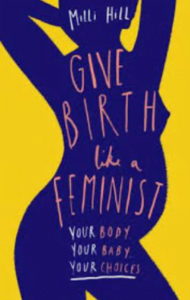

At a time in our social history where women and maternity care providers seem to have been persuaded that women’s bodies are deficient and women seem willing to abdicate their power and sacrifice their bodies, to interventionist birth, we also review a very welcome addition to birthing literature, Milli Hill’s, “Give Birth Like a Feminist”.

International Confederation of Midwives (ICM)

Midwives – The Guardians of Physiological Pregnancy & Birth

In this International year of the Midwife, MSCC thought it useful to remind our readers of the International Confederation of Midwives’ (of which NZCOM is a member) definition and philosophy of midwifery both of which make it clear that midwives are charged with optimizing the normal biological processes of pregnancy and birth; advocating for the use of medical intervention and technologies only when necessary; and ensuring that their practice is evidence-based.

Definition of Midwifery

International Confederation of Midwives (ICM), Definition of Midwifery

“Midwifery is the profession of midwives, only midwives practise midwifery. It has a unique body of knowledge, skills and professional attitudes drawn from disciplines shared by other health professions such as science and sociology, but practised by midwives within a professional framework of autonomy, partnership, ethics and accountability.

Midwifery is an approach to the care of women and their newborn infants whereby midwives:

- optimise the normal biological, psychological, social and cultural processes of childbirth and early life of the newborn;

- work in partnership with women, respecting the individual circumstances and views of each woman

- promote women’s personal capabilities to care for themselves and their families

- collaborate with midwives and other health professionals as necessary to provide holistic care that meets each woman’s individual needs

Midwifery care is provided by an autonomous midwife. Midwifery competencies (knowledge, skills and attitudes) are held and practised by midwives, educated through a pre-service/preregistration midwifery education programme that meets the ICM global standards for midwifery education.

ICM International Definition of the Midwife http://internationalmidwives.org/who-we-are/policy-and-practice/icminternational-definition-of-the-midwife/

Philosophy of Midwifery Care

ICM Philosophy of Midwifery Care

- Pregnancy and childbearing are usually normal physiological processes.

- Pregnancy and childbearing is a profound experience, which carries significant meaning to the woman, her family, and the community.

- Midwives are the most appropriate care providers to attend childbearing women.

- Midwifery care promotes, protects and supports women’s human, reproductive and sexual health and rights, and respects ethnic and cultural diversity. It is based on the ethical principles of justice, equity, and respect for human dignity.

- Midwifery care is holistic and continuous in nature, grounded in an understanding of the social, emotional, cultural, spiritual, psychological and physical experiences of women.

- Midwifery care is emancipatory as it protects and enhances the health and social status of women, and builds women’s self confidence in their ability to cope with childbirth.

- Midwifery care takes place in partnership with women, recognising the right to self determination, and is respectful, personalised, continuous and non-authoritarian.

- Ethical and competent midwifery care is informed and guided by formal and continuous education, scientific research and application of evidence.

Model of Midwifery Care

ICM Model of Midwifery Care

- Midwives promote and protect women’s and newborns’ health and rights.

- Midwives respect and have confidence in women and in their capabilities in childbirth.

- Midwives promote and advocate for non-intervention in normal childbirth.

- Midwives provide women with appropriate information and advice in a way that promotes participation and enhances informed decision-making.

- Midwives offer respectful, anticipatory and flexible care, which encompasses the needs of the woman, her newborn, family and community, and begins with primary attention to the nature of the relationship between the woman seeking midwifery care and the midwife.

- Midwives empower women to assume responsibility for their health and for the health of their families.

- Midwives practice in collaboration and consultation with other health professionals to serve the needs of the woman, her newborn, family and community.

- Midwives maintain their competence and ensure their practice is evidence-based.

- Midwives use technology appropriately and effect referral in a timely manner when problems arise.

- Midwives are individually and collectively responsible for the development of midwifery care, educating the new generation of midwives and colleagues in the concept of lifelong learning.

ICM. 2011. Core Document. Definition of the midwife

Midwifery in AotearoaNZ

In AotearoaNZ, the midwife works in partnership with women, on their own professional responsibility, to give women the necessary support, care and advice during pregnancy, labour and the postpartum period up to six weeks, to facilitate births and to provide care for the newborn

Midwife Shortages

During 2019 the shortage of both hospital employed and LMC midwives, in many parts of the country, worsened. The situation is so bad in places that it became newsworthy and during the year we saw regular reports about the causes and effects of this shortage in our media. A decade or more of underpayment and undervaluing of midwifery at both Ministry of Health and DHB levels, has contributed to the fact that midwives are leaving the profession after an average of only 6 years of practice. Midwives are leaving midwifery for less stressful, better paid work in other sectors and this has led to more stress and burnout for those remaining, contributing in some places to an inability to provide a desirable level of care to mothers and babies, lower job satisfaction and stress related illness, and ultimately more midwives leaving midwifery practice.

Direct action and lobbying resulted in an acknowledgement, by the current Labour coalition government, of a worsening situation for midwives and midwifery and has led to some improvement in: the remuneration of both employed and LMC midwives; the numbers of students entering midwifery training and; DHB campaigns to attract local midwives to return to practice and overseas trained midwives to migrate to AotearoaNZ.

Hospital/Birthing Unit Employed Midwives

The first half of the year was peppered by public campaigns that formed part of what had become, a two year long process, to renew the multi-employer collective agreement (MECA) to improve the pay and conditions of employed midwives. DHB employed midwives took strike action, joined pickets and marched on Parliament to demand recognition that, midwives are an essential and irreplaceable part of the health workforce; midwifery has a different skill set and training base from nursing; and that there was a long overdue need for separate payment scale that reflects midwifery training and practice rather than sharing a pay structure with nurses who do not have the skills or training to replace midwives in the workplace. Happily, the employed midwives union (MERAS) and the DHBs finally agreed to a settlement that included a 14–19.8% pay increase for midwives and are continuing to negotiate a pay equity claim that will likely result in further pay increases.

These increases in and changes to, the payment structure of hospital employed midwives, will hopefully support retention of existing midwifery staff and encourage some midwives who have left the service, to return. It is gratifying to see that the Midwifery Accord between the midwifery union (MERAS), the NZ Nurses Organisation,

DHBs and Ministry of Health, that was signed off in April, includes a commitment to address safe staffing levels. Hospital based midwifery shortages have snowballed resulting in insufficient numbers of midwives per shift. This has created more work, responsibility and stress for those remaining (including new graduates who are often unable to access experienced support and second opinions to deal with complexities) and this has led to further resignations from both experienced and new graduate midwives. As a result, most hospitals have been operating with unsafe midwifery staffing levels. Midwifery staffing shortages will not be resolved overnight, safe staffing initiatives, however, should help ensure that when the workload exceeds the midwives available to provide safe care, the senior midwife on duty can instigate actions that will ensure the health and safety of not only the mothers and babies on the wards, but also the midwives providing care, by e.g. having the ability to call in additional staff (midwives if available – though gaps will often have to be filled by nurses and health care assistants); negotiating with the duty manager and obstetric staff to delay non-urgent, elective inductions and caesarean sections and; negotiating with LMC midwives to discharge well mothers and babies to a Primary Birthing Unit (if they aren’t all closed!!) or home. (MSCC would add, where practicable, recommending that low risk women in labour divert to the nearest PBU instead of arriving at an understaffed hospital.)

LMC Midwives

Nearly four years since NZCOM entered mediation with the MoH to negotiate for changes to the funding model for community-based LMC midwives within a pay equity framework, the changes defined and agreed to in the resulting co-design, including a restructuring of the service specifications and payment modules to reflect the care and services that midwives actually provide, have yet to be implemented.

In late July 2016, just days before the start a judicial review instigated by NZCOM, into the failure of MoH to adequately recompense midwives for the services they provide in breach of Section 19 of the NZ Bill of Rights arising from both direct an indirect systemic and historical discrimination based on the fact that most midwives are women, the MoH presented an offer to NZCOM to have the case heard in mediation rather than in the court. NZCOM agreed to mediation because they felt that this would provide, a faster(?!) route to pay equity than the Court action.

A copy of the completed “Co-Design Model was given to the new Labour Minister of Health, David Clark, in late 2017 in the hope that he would ensure that sufficient funding to stem the flow of midwives out of LMC practice, would be included in the May 2018 budget. In early 2018, as LMC midwife burnout and shortages escalated, a small group of midwives, instigated the “Dear David” social media campaign to support the need for urgent implementation of the recommendations for increased funding of LMC services. The 2018 and 2019 budgets did allocate small increases (8.9% and 4.9% respectively) to the existing Section 88 modules, but none of the changes to the funding model agreed to in the co-design have been implemented. While 8.9% sounds like a big increase, it equated to payment of just an additional $200 per woman for the full 8-9 months that most women are receiving care from their LMC and totally fails to address payment for the ever-enlarging scope of care and increasing numbers of referrals etc (all of which require informed choice conversations and a trail of paperwork, follow-up and filing) that LMC midwives are required to provide to their clients. The only change/addition to the payment schedule has been a welcome broadening of access to payment for a second/back up midwife during labour to assist or takeover when the LMC has already provided hours of care or when the LMC is already providing care for another client in labour. The May 2018 budget also allocated one-off funding for a “Business Contribution Payment”, a payment to Lead Maternity Care midwives to contribute to the costs of being self-employed. No funding has been made available for payments after the 2019/20 financial year, which ends on 30 June 2020 which hopefully indicates that more comprehensive LMC payment changes will be implemented by this date and midwives will not have to apply in an ad hoc way for recompense for the huge amount of time and the costs associated with providing LMC midwifery services. Unfortunately, these minor funding increases have proven to be “too little, too late”. Increasing numbers of both rural and urban pregnant women are unable to access LMC midwifery care as midwives continue to leave the service. NZCOM has now instigated a public #backmidwives campaign asking the community to sign a petition that will be presented to the government in 2020 in a last ditch effort to get the Minister of Health to prioritise funding of the co-design and a sustainable payment structure for LMC midwives. MSCC hopes that in the International Year of the Midwife, that our government implements the payment reforms that are necessary to sustain the essential and much appreciated LMC midwifery workforce.

Primary Birthing

Midwives are best able to “optimise the normal biological, psychological, social and cultural processes of childbirth and early life of the newborn” when women birth in primary settings, either at home or in a midwifery-led Primary Birthing Unit.

During 2019 MSCC continued our decades long campaign of, lobbying for the provision of more and accessible primary birthing options and encouraging women and their whanau to choose primary birthing options. As far as MSCC is aware, there were no DHB funded Primary Birthing Units built or opened in 2019 rather, a number closed or were threatened with closure.

2019 saw the publication of a number of three well designed pieces of research from a range of countries in the world, proving, what many women and midwives know, that mothers and babies have better outcomes and are exposed to less medical intervention when they birth in a primary environment. In addition, here in AotearoaNZ, annual maternity reports from the MoH, the DHBs, the National Maternity Clinical Indicators, the National Maternity Monitoring Group show both, that healthy pregnant women in AotearoaNZ are being exposed to a model of maternity care that is mostly, unnecessarily, intervention-heavy and that birth in primary settings reduces the chances that women will experience unnecessary and expensive medical interventions.

Recently Published Evidence Supporting Primary Birthing

Comparing perinatal outcomes for healthy pregnant women presenting at primary and tertiary settings in South Auckland: A retrospective cohort study.

Farry, A., McAra-Couper, J., Weldon, M.C., & Clemons, J. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal, 55, 5-13. https://doi.org/10.12784/nzcomjnl55.2019.1.5-13

“The aim of the study was to identify whether place of birth affected measurable maternal and neonatal outcomes” for a group of low mothers. This retrospective study compared the outcomes of 4,207 low risk women, who had birthed in either Middlemore Hospital (TMU -tertiary maternity unit) or one of three DHB funded primary birthing units (PMU – primary maternity unit) in South Auckland. For this study, the definition of low-risk, required: that women started labours at term (37-42 weeks gestation) and were not induced; that their singleton baby was in a cephalic presentation (head first) at the onset of labour; that they had had no maternity related admissions to hospital during their pregnancies or during labour; that the mothers were < 44 years old if they had already given birth and were < 40 years old if this was their first labour. All the women included this study had a BMI of <40 and were registered to receive their maternity care from an LMC midwife at least 2 weeks before going into labour.

Of the 4,207 women in this study, 26.5% (1,114) gave birth at a PMU and 73.5% (3,093) at Middlemore(TMH). The TMH cohort had a higher percentage of first time mothers (39%) compared with the first time mothers in the PMU cohort (29%). 18% of first time mothers and 3% of women who had already given birth were transferred from a PMU to the Middlemore during labour (75 women). A further 2.6% (29 mothers and babies) were transferred to the TMH within 12 hours of giving birth.

This study found that women giving birth in a freestanding PMU had lower rates of emergency caesarean section, PPH, and admission of mothers to theatre or intensive care after giving birth. The babies born in a PMU higher APGAR scores at 5 minutes and half the rate of neonatal admission to Neonatal Intensive Care (NICU). Low risk women birthing at the TMH were 4 times more likely to give birth by c-section; five times more likely to need intensive care immediately after giving birth and; twice as likely to have a postpartum haemorrhage.

“This research adds to the growing body of international research on freestanding PMUs, confirming them as physically safe places for well women to give birth when midwifery is properly integrated into the maternity system…”

Perinatal or neonatal mortality among women who intend at the onset of labour to give birth at home compared to women of low obstetrical risk who intend to give birth in hospital: A systematic review and meta-analyses.

Hutton EK, Reitsma A, Simioni J et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jul 25;14:59-70. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.07.005. eCollection 2019 Sep.

This systematic review and meta-analyses aimed to discover if the risk of fetal or neonatal death differs among low-risk women who begin labour intending to give birth at home compared to low-risk women intending to give birth in hospital. Information was collated from 17 studies dating from 1990 onwards, which compared neonatal outcomes from 500,000 planned home births and the same number of planned hospital births. The women in both groups were matched as closely as possible for age, risk, demography etc. and their care providers who also matched as much as possible.

The countries from which the data originated included the US, Canada, Sweden, England, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand and Japan.

0utcomes were reported according to planned place of birth, not actual place of birth. The primary outcome analyzed was the death of the baby from after the onset of labor up to 28 days post-childbirth. Other outcomes recorded were, the number of babies who required resuscitation at birth or who had low Apgar scores, and the numbers of babies who needed to be admitted into a neonatal intensive care unit.

The results showed that there is no difference in the outcomes for babies who were born following a planned homebirth compared with those born in a planned hospital birth regardless of whether the mother was giving birth to her first baby or had already birthed a baby/babies. The meta-analysis of studies which reported on Apgar scores and NICU admissions showed that babies born at home were less likely to have low Apgar scores and less likely to need to be admitted into a NICU.

Women with risk factors and planned homebirth

The review’s original intent was to compare low-risk women planning home and hospital birth, however, they noted that some studies included all planned home births and included some mothers and babies who were considered to have risk factors e.g. women carrying twins or breech babies and women who had had a previous c-section. Even when they compared data for all women planning a homebirth with only low risk women planning a hospital birth, there was no difference in outcomes for the babies. Interestingly, the authors recommended that maternity care systems must address the reasons why some women with risk factors choose home birth and concluded that, “Maternity care systems should provide safe, evidence-based, humane hospital care that is respectful of the right of childbearing women to make decisions about their care.”

It seems to us that this recommendation makes the assumption, in spite of the evidence, that hospital birth is safer for any woman with obstetrically defined “risk” factors. There are a variety of reasons why a small number of women choose to give at home in spite of their apparent risk status including that …

- many hospital/health authority protocols and practices for the management of women with risk factors include (often non-evidence-based) restrictions and negative attitudes that make it difficult or impossible for women to feel confident that they will be supported to achieve or even attempt a physiological labour and birth.

- they are unhappy with, or traumatised by, the “care” they received during a previous hospital birth, (which may have resulted in the outcomes that label them “at risk”) and choose not to be exposed to the system of care, routine interventions or restricted choices that will occur in a hospital environment.

What this analysis does not seem to consider is that, some women simply prefer to labour and birth in their own homes. They know their bodies and have confidence in their ability to carry out this inherently normal function; they believe that home is the most appropriate place for their labour and birth and is also the birthplace most likely to support the best outcomes for themselves, their babies and their whanau. These women are neither careless of, nor oblivious to, the concept of “risk”, they simply reject the dominant fear and control based model of maternity care, choosing not to avail themselves of medical assistance unless this actually becomes necessary. They have confidence in both their bodies and their ability to make an informed choice in partnership with their chosen midwife, if actual indicators of risk of harm arise during the labour and birth.

MSCC extremely grateful to the midwives who support any women medically defined as having “risk factors” to birth at home, even though the personal and professional risks and stress associated with this support of women’s autonomy can be considerable. Hopefully these midwives and their colleagues will feel vindicated and supported by the outcomes of this huge review that shows that medically defined risk factors are simply something that needs to be factored into informed decision-making. Medically defined “risk” does not trump any individual woman’s knowledge of her own body and, in the case of place of birth, her ability to choose the environment that she believes is most likely to support her and her baby to experience the immediate and longer term benefits of physiological birth.

Maternal and perinatal outcomes by planned place of birth in Australia 2000 – 2012: a linked population data study.

Homer CSE, Cheah SL, Rossiter C, Dahlen HG et al. BMJ Open. 2019 Oct 29;9(10):e029192. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029192.

This study examined outcomes of 1,251,420 full–term (37 – 41 completed weeks of pregnancy) births to low risk mothers carrying a singleton baby that occurred throughout Australia between 2000 to 2012. Of the 1,251,420 births, 1,171,703 (93.6%) were hospital births, 71,505 (5.7%) were birth centre births and 8212 (0.7%) were homebirths.

The study measured rates of, different modes of birth (vaginal, forceps ventouse assisted, c-section); intervention during labour and birth; maternal complications; admission to special care/high dependency or intensive care units (mother or infant); and perinatal mortality (intrapartum stillbirth and neonatal death).

This comparative review showed that the odds of normal labour and birth were nearly three times as high when women planned to birth in a birth centre and nearly six times as high in planned home births than for a similar low risk women birthing in a hospital regardless of whether the women were birthing their first or a successive baby.

Maternal Outcomes

Women who planned to birth in hospital experienced a higher rate of all the interventions measured than women who planned to birth at home or in a birth centre. The percentage of women (who gave birth vaginally) who had an intact perineum was lower for women who planned a hospital birth than women who birthed at home or in a birth centre.

There was no significant difference in the rate of the maternal postnatal complications measured in this study i.e. postpartum haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion, maternal admission to intensive care or high dependency unit and maternal readmission to hospital within one month of giving birth.

Baby outcomes

The data related to stillbirth during labour, early and late neonatal death indicate that perinatal death is no more likely to occur after planned birth centre or homebirth than a planned hospital birth. There was a slight increase in the perinatal mortality rate for first time mothers birthing at home (0.8 per 1000 in planned hospital vs 1.7 per 1000 in planned homebirth). However, the authors state that, “Given the small number of deaths in the planned homebirth group (n=9) this may be a chance finding over a long period of time (13 years).”

In this study women who planned a birth centre birth were more slightly more likely to have their baby admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit for longer than 48 hours than women who planned homebirths or hospital births but planned place of birth resulted in no significant difference in the rate of readmission to hospital of babies within 28 days.

Implications for practice

The authors go on to state that, “The lower odds of maternal morbidty and obstetric intervention support the expansion of birth centre and home birth options for women with low-risk pregnancies.”

Is Maternity Service provision in AotearoaNZ really evidence-based?

MSCC wonders why women, their maternity care providers and our health and government authorities are ignoring this evidence, evidence that, for decades now, has shown that primary birthing options are not only safe but also deliver consistently better health outcomes at lower financial cost . A large percentage of women in AotearoaNZ do not have reasonable access to a primary birthing unit/centre and our DHBs seem to be more interested in looking for excuses to close PBUs than actively supporting and promoting this option. Although some of our DHBs have mooted the idea of building new PBUs in their catchments e.g. Waitakere (DHB commitment), Wanaka area (DHB commitment), Dunedin(DHB commitment to a feasibility study), the years it takes to make any progress towards the establishment of these birthing facilities indicate that they are given the lowest possible priority. When however, the private sector steps in and establishes much needed PBUs, some DHBs are reluctant to share funding e.g. Counties Manukau and Hutt Valley DHB. Every year our DHBs spend increasing amounts of money on the increasing numbers and rates of pregnancy and labour interventions, not to mention, the costs of the associated short and long term morbidity arising from our culture of interventionist birth for both mothers and babies. They ignore the evidence that shows that encouraging and providing (or funding) access to primary birthing options, would save them money and provide much better short and long term health outcomes for women and their babies.

Relative Cost Effectiveness

MSCC is not aware of any local analysis of the comparative costs of homebirths, primary birthing unit births, secondary and tertiary hospital births. However the data supporting the low rate of interventions (plus the known maternal and infant morbidity associated with these) would make birth at home or in a Primary Birthing Unit considerably more cost-effective than birth in a secondary or tertiary unit. (In addition, a successful planned homebirth saves thousands of dollars in facility costs because the woman/whanau are providing the “facility”.) The studies summarized above show that financial costs associated with hospital births where a higher percentage of “low risk” mothers and babies receive anaesthetic services for epidural and c-section, specialist obstetric input for all interventions, obstetric and theatre costs associated the burgeoning c-section rate, increasing use of neonatal care intensive care services and maternal intensive care/high dependency services, not to mention the higher overall costs of operating a secondary or tertiary obstetric facility, would mean that birth and postnatal care in a PBU would cost a fraction of the cost of hospital birth.

If neither high quality evidence of positive health outcomes nor cost-effectiveness can persuade our health authorities to provide and promote primary birthing options we wonder what will??!!

Updates on Primary Birthing Units (PBUs) in AotearoaNZ

Southern DHB

Lumsden Maternity Unit

In our September 2018 newsletter, MSCC provided a backgrounder to Southern DHB’s (SDHB) decision to close the Lumsden Maternity Unit. Despite petitions and submissions from the community and the support of the National Maternity Monitoring Group, the unit was closed in April 2019.

SDHB Report: Primary Maternity Project

In the SDHB’s “Report: Primary Maternity Project”, released in May 2017, it was reported that, “women felt there was insufficient information on the benefits of primary maternity services and entitlements to these services. They requested independent and objective information to support decision-making.”(p13) In addition, “Feedback from consumers, midwives and providers reflected that transport/transfer is a major issue in the Southern District. There is a widely held perception that current systems may not consistently ensure timely transfer. “(p16)

Consumer feedback stated clearly that women/whanau in the Southern DHB catchment, (and MSCC suspects throughout the country), need more objective information regarding the benefits of primary birthing. There is an ever-growing body of evidence supporting primary birthing and there is an urgent need that this be translated into user-friendly resources that are widely disseminated by the MoH, DHBs and individual maternity care providers. Secondly, it is hardly surprising that the absence of robust and confidence inspiring systems for emergency transfer leads women in provincial and rural Southland to choose to travel for hours to birth in a base hospital rather than in a more local PBU. In another example of a Clayton’s consultation, neither of these issues was adequately addressed in the subsequent plan for an Integrated Primary Maternity System of Care across the Southern District

This report went on to note that there were differences in funding packages for individual PBUs but that most had “requested additional funding to meet operational costs indicating that financial sustainability is a critical issue as they cannot provide financially sustainable services within existing funding…with most finding it increasingly difficult to manage compliance costs for audits, health and safety requirements, policies and procedures, quality systems, certification and Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiatives. There are overheads associated with management and workforce costs, as well as the upgrades to the physical environment such as birthing pools, access to WiFi, double beds which enable partners to stay overnight and ensuite bathrooms.” (p14)

This report made no mention of the fact that the funding of the PBUs from the DHB, had remained pretty much static for years covered by this review (2011 – 2015) as had the payment schedule for LMC midwives from the MoH. (In 2015 LMC midwives received their first pay increase, a measly 2.5%, since 2007.) As a result, many more midwives were leaving LMC practice than taking up LMC contracts leading to an LMC midwife shortage – women cannot birth in PBUs unless they are supported by an LMC midwife.

“Creating an Integrated Primary Maternity System of Care across the Southern District.” Southern District Health Board (August 2018)

The Lumsden PBU, like many others throughout the country, was developed by the community and owned by a trust. Lumsden PBU was run by the Northern Southland Health Company and received $370,000 operational funding per year from the SDHB.

Prior to closure approximately 38 women gave birth at the unit each year with a similar number transferring from either Invercargill or Dunedin obstetric units for inpatient postnatal care. Instead of promoting and supporting increased use of the PBUs in it’s catchment, SDHB produced a proposal for an “Integrated Primary Maternity System of Care” in March 2018 in which the closure of Lumsden PBU was signalled. SDHB had decided that a more equitable distribution of maternity services in the region would be achieved by converting the Lumsden Unit to a “Maternity Hub” and establishing other such hubs in Wanaka and Te Anau, Tuatapere and Ranfurly. The proposed “hubs” would provide a space for antenatal and postnatal consults (including possibly base for telemedicine consults, space for visiting specialist consults and potentially a meeting space for other community support organisations). “The space will ideally be co-located within or near to a General Practice, or operate as part of a Community Healthcare Hub. This will enable LMCs to have increased access to other health practitioners and work as part of a broader team, particularly in rural or isolated areas.” (p11) Crucially, the DHB stated that it would equip the hub with basic midwifery equipment, consumables for the use of LMCs, and emergency equipment in the event that rapid births occur outside of travel distances to a primary birthing unit.?”(p11)

The Lumsden PBU had been closed and supposedly converted to a “maternity hub” for over one month before emergency equipment was provided. Prior to August 2019, midwives found the hubs “locked” (either because locks had been changed or because there was no process established for after hours access), lacking both basic and emergency resuscitation equipment to support safe birthing. No contracts for regular cleaning or any systems for rapid heating of the spaces in the event of emergency births outside of times when the “hubs” might be being used for antenatal consults etc. In fact, it was only after four widely publicised emergency/roadside births in the district that all the “hubs” were properly equipped and set up for emergency births. Wanaka still has a temporary “hub” and the location chosen for the new “hub” is not near the helicopter pad, medical centre or midwives’ offices (so neither practical nor confidence inspiring in the case of emergency births), and will not be up and running until later in 2020. In short, a comfortable, well-equipped (albeit underused) primary birthing facility which already provided space for pregnancy and lactation consults etc and had 24 hour employed midwife cover was closed and replaced with a basic facility for emergency birthing. Public reaction to the Lumsden PBU closure indicated that women and their families were not fooled into thinking that even a well-equipped hub could provide what they needed, i.e a warm, primary birthing facility with a second midwife on site or on call, equipped with a pool and other equipment that aided physiological birth but also fully equipped for emergencies, a local facility that provided a comfortable place to recover, rest and be supported to establish breastfeeding etc for a few days before returning home (often to a remote, rural location) with a newborn baby. It is disingenuous of the DHB to try to sell the idea that “maternity hubs” would improve the quality to maternity care currently available to women/whanau in provincial and rural Southland.

SDHB considered that maintaining Lumsden as a PBU was economically unviable, but since 2017 has spent thousands on reports into maternity service provision by private consultants, the most recent of which, a “Mid Implementation Review: SDHB Primary Maternity System of Care” by consultancy firm Ernst and Young, echoes the concerns of the 216 submitters to the 2017 Maternity Plan and the 5000 who signed petitions requesting that the Government direct SDHB retain the primary birthing facility in Lumsden.

Mid Implementation Review: SDHB Primary Maternity System of Care

This review focused on the implementation of the actions described the SDHB’s Maternity Strategy from its publication in August 2018 through until 31 July 2019.

Rob Houlahan from the Otago Daily Times (ODT 9/11/19) summarised the report’s findings: – “The Southern District Health Board’s well-intentioned plans to improve maternity services in the South instead led to confusion, miscommunication, overdue actions and unintended consequences, a review released yesterday said.

Independent assessors Ernst and Young found the strategy’s nine key actions were not defined in detail, not formally tracked, and nor was it set out what entailed those actions being done.

Governance was informal, unclear, inconsistent and lacked accountability, while project management “lacked the level of maturity required for a project of this scale”.

The review sought to better target provision of maternity services across the whole SDHB region, and proposed creating maternal and child hubs in several towns – controversially so in Lumsden, Te Anau and Wanaka.

However, what a hub actually was and did was “vague and undefined” and had led to mixed or misinformed messages and a “misalignment of expectations”, the report said.

Adding to the shambolic roll-out of the strategy, key roles remained vacant at critical periods, and the strategy’s project management role had been vacant since February. That resulted in equipment which was meant to be in hubs not arriving before they opened, no common agreement between the DHB and the communities about what a hub was, and people intended to be co-ordinating the hubs not knowing that was what was expected of them.”

New Primary Birthing Units for Southland – don’t hold your breath! “Action 7: Consideration to be given to the most appropriate location for a primary maternity facility within the Central Lakes district.”(p15) (with the suggestion that the

PBU in Alexandra (where birthing rates are apparently falling) would be closed in favour of relocating this service to the Central Lakes/Wanaka area where the population is rapidly growing.

The lack of primary birthing options in the urban centres was addressed in “Action 9: Consideration of a primary birthing unit in Dunedin, in conjunction with the new Dunedin Hospital rebuild, is undertaken by way of a feasibility study.”

The Ernst & Young Report considers that it is unlikely that; Action 7 – related to the planning for a new primary birthing unit in the Central Lakes District, which is urgently needed due to rapid population growth occurring in this area; or Action 9 – a feasibility report to consider including a PBU in the Dunedin Hospital rebuild; will be achieved by the proposed June 2020 deadline.

Public consultation on Public consultation on Central Lakes maternity services opened at the beginning of February 2020. The Otago Daily(ODT) Times (5 February 2020) reported that “SDHB chief executive Chris Fleming said that deadline had been ‘‘aspirational’’ and might not be met”.(!!!)

When is a birthing unit not a birthing unit? … When it’s a hospital ward

On 11 March (ODT) reported that SDHB will include a primary birthing unit alongside its new maternity ward in the new complex’s acute services building! It is disappointing that the DHB has gone for the cheapest option, once again demonstrating what the low priority status given to mothers and babies as well as a disregard for the evidence that shows that stand-alone PBUs have the best physiological birth outcomes.

A quote from Chief Executive Chris Fleming, signals that this PBU will indeed just be a maternity ward, “We believe the development of an appropriately configured facility that would enable some back-up and infrastructure for each other (our emphasis) but which would be operated as two separate units is a good balance.” MSCC wonders if any women were consulted prior to making this decision. The article quotes New Zealand College of Midwives Dunedin representative Maureen Donnelly as saying, “What the DHB called a primary birthing unit and what midwives thought one was were not quite the same thing.” We women agree. Again, this Chief Executive shows his dismissive attitude to the women of the district in his “take it or leave it” statement, “It is fair to say there are still some who gave a view that the primary birthing unit should be completely stand-alone and off-site; there is nothing stopping any parties out there developing primary birthing units. There are units which are not DHB-owned.” MSCC would like to remind Mr Fleming that it is the responsibility of the tax-payer funded DHBs to provide appropriate and evidence-based services to their communities. Women’s access to safe and appropriate birthing facilities should not be dependent on private sector philanthropy or individual women’s/whanau’s ability to pay. The DHBs have a poor record when it comes to public:private partnerships with privately established PBUs.

Waitakere Primary Birthing Unit

Here in Auckland there has been a spectacular lack of progress on building the proposed Waitakere PBU. In 2017 the Waitematā DHB said it would build a primary maternity unit at the Waitakere Hospital site by June 30, 2020. In 2017 the board said: “The unit would be built on the Waitakere Hospital site … with a goal of completion in the 2019/2020 financial year.”(i.e. 30 June 2020) In July 2019, NZHerald was told, “The DHB is currently exploring site options.” In December 2019 MSCC was told, following a lengthy and extensive process of consultation with key stakeholders and maternity consumers, that no location for this facility had been finalised and that the DHB would make a decision by April 2020!

Ōpōtiki Primary Maternity Unit

On 28 November 2019 the Bay of Plenty District Health Board (BOPDHB) issued a Press Release notifying that they were suspending services at Ōpōtiki Primary Maternity Unit from 1 December 2019 to 30 March 2020 due to inadequate staffing of midwives. The safety of women and their babies is paramount in this decision.

The Press Release went on to say that, “Like the rest of the country we are facing a shortage of midwives and that’s had an impact on our ability to keep operating safely in this timeframe.

There are not enough midwives in the area to provide back-up to the woman’s LMC midwife to support women to deliver their babies safely at the maternity unit.

We know this decision will have an impact on expectant mothers who are due to give birth at Ōpōtiki Maternity Unit and we apologise for the impact this will have on their birthing plans.

We cannot solve these issues alone and are committed to working with the community to build a sustainable and equitable maternity system across our whole district.

We have been in discussions with midwives in Ōpōtiki and other health providers about a sustainable service going forward. We will continue to engage with midwives, other health professionals and the Ōpōtiki community to determine how best to meet the needs of local women and their whānau.

We advise expectant mothers to talk to their Lead Maternity Carers (LMCs) about their individual birth plans and alternative options which include either birthing at Ko Matariki Maternity Unit, Whakatāne Hospital or in some cases delivery at home…”

Local media spoke to LMC midwives in the area who were taken by surprise at the sudden notice of closure. They said that there was no change in the numbers of LMC midwives available than before 1 December and that apart from one meeting in early 2019, they had not been consulted. Four LMC midwives support 50 – 70 women to give birth at this unit each year and some women transfer back from Whakatane for postnatal only care. Staff at the Maternity Unit reported that they had only received 3 days’ notice of the closure. Local women were dismayed at the thought of adding 40 – 60 minutes in a car in labour to get to Whakatane, some saying that the closure would give them no choice but to birth at home. It would take women from around the Eastern Bay area, such as Waihau Bay and Te Kaha, about two or three hours to get to Whakatāne Hospital. BOPDHB’s acting chief executive, Simon Everitt, said closing the birthing unit was a difficult call but that they didn’t have enough midwives to cover on-call shifts.

On 3 January, BOPDHB issued another Press Release announcing that birthing services at the Ōpōtiki Health Centre Birthing Unit had recommenced on an interim basis (our emphasis) on 1 January.

“The Ōpōtiki midwives and the Bay of Plenty District Health Board are pleased to announce that birthing services at Ōpōtiki Health Centre recommenced on 1st January 2020 on an interim basis.

During December, much work was done to ensure we have a safe and supportive model of 24- hour cover for local births. Training has been provided for local nurses and St Johns to act as support to midwives and additional locum midwife cover is in place until the end of January as part of an interim arrangement.

Work will need to continue to ensure that we are able to maintain the roster cover after January and at the end of the month we will review the interim arrangements to make sure they are working well for everyone involved.”

After the closure was announced members of the local community immediately launched a petition and within days over 5,000 people (more than half the population of Opotiki) had signed. MSCC wonders why BOPDHB could not have done the work necessary to ensure that they were able to provide care to the whanau of the area, before abruptly announcing the closure of this unit. LMC midwives report that during December they had several women from Opotiki and further up the Cape birth within 10 minutes of arriving at Opotiki which means that they would have coped with all their active labour in transit – an uncomfortable and unsafe and unacceptable situation It seems that the needs of pregnant women are low priority in this DHB and one cannot help but think that the timing of this announcement allowed the DHB to save on the penal rates it would have had to pay to staff the Opotiki Birthing Unit over the Christmas and New Year statutory holidays. BOPDHB has stated that this is just an interim arrangement, however, there was no mention of the situation in Opotiki or any suggestion of debate about, a longer-term solution in the public minutes of the February Board Meeting. MSCC hopes that the women/whanau of this region do not continue to have the threat of imminent closure of their birthing unit hanging over them for months to come.

Hutt Valley

Nga Hau and Te Awakairangi Birthing Units

Two Birthing Units established by Birthing Centre, a subsidiary organization of the philanthropic Wright Family Foundation, Te Awakairangi (Hutt Valley) and Nga Hau (Mangere) were forced to close between 20 December 2019 and 6 January 2020. The Christmas/New Year holiday season is a particularly expensive time for any business due to the need to pay staff penal rates on public holidays and because these two PBUs have no DHB funding, they could not be kept open over this time. In the last two years, the Wright Family Foundation has donated approximately $2.5million to cover the operating costs of these PBUs. This philanthropic foundation has been encouraging DHBs to recognise that primary birthing facilities are a solution to the escalating maternity care crisis in New Zealand, to enter into a partnership with their subsidiary, Birthing Centre, and fund the running costs of these privately built PBUs that give women in these communities an accessible option of birthing and receiving postnatal care in a local PBU.

Hutt DHB continues to decline to provide any funding to Te Awakairangi Birthing Unit that has now been open for two years despite the fact that there is no DHB PBU option in the area. Similarly Counties Manukau DHB (CMDHB) continues to deny funding to Nga Hau in Mangere. A spokesperson for CMDHB was quoted in Stuff (30 Oct 2019) as saying, “We value the importance of choice for women. CM Health already has three primary care birthing units in the district – Papakura, Pukekohe and Botany, and our secondary care unit at Middlemore Hospital … Within these four units we have the capacity to meet the needs of our mothers and babies.” This comment, however, contradicts the findings of a report commissioned by this DHB in 2018 (Consumer Perspectives on Primary Birthing CMDHB:Moana Research , 2018) which showed that women’s ideal birthing environment included one that was close to home and allowed partners to stay postnatally. The Introduction to this report states:-

Mangere

“In Counties Manukau, the rate of women birthing at Middlemore Hospital has trended upwards, while women giving birth at one of the three DHB primary birthing units has decreased². One of the issues facing women with low risk pregnancies who live close to Middlemore Hospital and its surrounding suburbs is that there is no local primary birthing unit with some mothers having to travel more than 20km to access the nearest unit. This is not expected to change until a primary birthing unit is available locally. Nonetheless, with the high number of low-risk women choosing Middlemore Hospital, as well as the increased pressures placed on maternity services at Middlemore, Counties Manukau Health is keen to promote all birthing options available to pregnant women, including the benefits of a primary or home birth. As a result, Counties Manukau Health has set out the following aims:

- To increase primary birthing by 2% by June 2019

- Reduce intervention rates for low risk women

- Decrease the percentage (26%) of low risk women birthing at Middlemore hospital

- Improve customer satisfaction with service delivery at primary birthing units

- Engage Lead Maternity Carers and consumers in the project plan and implementation

In view of this statement and these aims, it is hard to understand CMDHB’s ongoing refusal to support this PBU in Mangere. Women living in the Mangere area do not generally consider Botany Downs or Papakura “close to home” either geographically and, with regard to Botany PBU in particular, they do not consider it culturally “close to home” either. Partners are not currently able to stay overnight in any of this DHB’s PBUs. One would expect the CMDHB would welcome the “gift” of a purpose-fitted PBU that will help them achieve their aim to decrease the numbers of low-risk women birthing at Middlemore and reduce the expensive and often unnecessary medical interventions these women are exposed to in their secondary facility.

Palmerston North

DHB takes over management of Te Papaioea Birthing Centre

In Palmerston North, MidCentral DHB (MCDHB) and the Wright Family Foundation announced that MCDHB will lease the building and take over the management of the Te Papaioea Birthing Centre from April 2020. Te Papaioea was built, and has been operated by the Birthing Centre/Wright Family Foundation for the past two years, but so far the 12-suite birthing centre has consistently operated below its capacity (although 634 babies were born at this PBU during its first two years of operation). In their Press Release MCDHB said:-

The agreement recognises what research has confirmed for many years: the importance of care in the first thousand days of life. Vital in this approach is putting mothers at the centre to achieve best outcomes for mother, baby, and whānau.

The venture will enable staff to move between both sites, implementing a flexible work flow to provide cross cover and enable staff opportunities of working in primary and hospital-based maternity settings.

MidCentral DHB’s Operations Executive for Te Uru Pā Harakeke Sarah Fenwick said both the DHB and the Wright Family Foundation are committed to ensuring the best possible primary birthing opportunities are presented to women, babies and whānau.

“There is clear evidence to suggest women with low risk pregnancies who birth at a primary setting experience better health outcomes and we are delighted to be a position where we can continue to provide the very best health services to our community in a safe and supportive environment. We are confident this change will be a positive one for the community and for staff working at the hospital and the birthing centre.” (Thursday, 12 December 2019, 12:03 pm)

Women on the Palmerston North Hospital FB page were a little more cautious about embracing this change to DHB management …

“I was fortunate enough to birth here earlier this year. That’s why I’m concerned about whether the quality will be preserved now…”

“…it’s a worry why mess with something that is good.”

“This one is my last baby so would love to have that close team. I’m hoping the care stays as high as it is in that case.”

“Wonder if it’s funding related and DHB had to take it over before they would share the $? It was nice having the small team of midwives caring for you postnatally…”

“So can we expect the quality of care to slip to the standard of that at the hospital, where the post-natal ward is staffed by nurses instead of midwives?”

“I think it’s quite sad the DHB is taking over, I hope for everyone’s sake the experience and postnatal care stays the same.”

MSCC joins these women in hoping that the DHB will maintain the high standard of care that mothers and babies have enjoyed while this unit has been under the management of Birthing Centre.

Book Review : Give Birth like a Feminist – Your Body, Your Baby, Your Choices Milli Hill HarperCollins, 2019

This is the first book written for several decades that explores the relationship between contemporary birthing beliefs and practices and feminism. Milli Hill’s definition of “feminism just means noticing when women are getting a raw deal and taking action.”

Hill takes a comprehensive look at the history of women’s disempowerment in the birthplace. Second wave feminists of the 1960s – 70s demanded equality for women in the home and the workplace; sought to deconstruct traditional gender roles; and reclaimed their bodily, sexual and reproductive autonomy. However advanced technology (i.e. ultrasound imaging and monitoring) and epidural anaesthesia allowing women to be conscious and aware but have pain relief for labour and caesarean surgery, entered maternity hospitals as these 20th century feminists left to birth at home or in midwife led birthing centres. Mainstream birth culture and maternity systems and our collective trust in technology has disempowered women as mothers. Fear, rather than evidence, intuition and trust in a process that has guaranteed the survival of our species for millennia, dominates the options women are given and the choices they make. With intervention rates at an all time high, women are encouraged to believe that their bodies let them down rather than a system which tries to impose control over an amazingly individualistic process. Spoken or unspoken threats of harm to our babies, rather than good quality evidence undermine women’s confidence and autonomy and ensure compliance with the current interventionist model of maternity service provision.

Hill addresses all these issues in chapters entitled “Am I allowed”, “When women’s bodies became men’s business”, “Women’s bodies unfit for purpose” , Birth rights are women’s rights are human rights”. She sets out to show that many women’s experiences of birth, especially in her country(UK), are dominated by antiquated, patriarchal, non-evidence-based practices that frequently harm women (mentally and physically), and deny them their human right to bodily autonomy and informed choice.

This is not a practical manual like Hill’s, “Positive Birth Book” neither is it an academic treatise on feminism in the birthplace. It presents a wide-ranging view feminism and birth. There are, however, a few shaded pages in each chapter with practical suggestions that may assist pregnant women to be active, feminist participants in their maternity care choices.

It is not a book that exclusively promotes physiological birth as the feminist norm. Hill makes the point that a truly feminist perspective requires that individual women’s dignity, autonomy and human rights are respected regardless of the choices she makes.

Milli Hill uses her own experiences and those of other women (from around the world) to illustrate how common and widespread the abuse of women and the denial of their human rights in childbirth, are.

This book does not demonise doctors and midwives, rather, it articulates how mainstream birth culture and maternity systems continue to disempower women and often midwives as well. She challenges maternity care providers to respect and facilitate women’s rights and choices in maternity and to offer only evidence-based care. This book will hopefully inspire and encourage women to reclaim their birth rights and abilities and become truly active participants and primary decision-makers in their maternity care. The evidence shows us that women’s health and that of our babies, requires women to Give Birth like a Feminist!

MSCC WELCOMES input, feedback and suggestions: Email [email protected]

We also invite any women who are interested in maternity related issues to participate in our monthly STEERING GROUP MEETINGS. If you would like to observe, add your voice or contribute your skills to our organization, please phone 022 421 6008 to arrange to meet us.