WELCOME, TENA KOUTOU KATOA, KIA ORANA, TALOFA LAVA, MALO LELEI, FAKAALOFA ATU.

Welcome to the June 2019 issue of the MSCC’s Newsletter.

- Report on Maternity 2017

- Women

- Ethnicity

- Geographical Distribution

- Parity – Number of births per woman

- BMI & Smoking

- Babies

- Gestation

- Birthweight

- Type of Lead Maternity Carer (LMC)

- Normal Birth

- Breech births

- Caesarean Section

- Induction of Labour

- Epidural Pain Relief

- Augmentation of Labour

- Instrument Assisted Births and Episiotomy

- Multiple Birth

- Place of Birth

- Home Birth

- Breastfeeding

- Handover of Care

- BreastfeedingWhat the stats say and don’t say… and what women say

The Ministry of Health (MoH) recently published the, “Report on Maternity for 2017”. For an organization that celebrates and promotes the intricate hormonal & physiological processes pregnancy, birth and the mother: baby dyad, processes that have determined the survival of our species into the 21st century, the 2017 Report on Maternity is disturbing reading. Less than 50% of women in New Zealand are experiencing this amazing life transition without the assistance of medications and medical interventions. Does our community, our “civilization”, really believe that this percentage of women, out of necessity or choice, need access to this ever-increasing quantity of intervention? Have we agreed that we are willing to continue to put more and more resources into the medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth? Are we ignoring the evidence regarding the postbirth impacts of all this intervention?

During the past year we have seen, mostly young people, lying down in the streets to symbolize the threat to their lives and futures, arising from the lack of acknowledgement of, and action to halt, climate change. Is it too dramatic to suggest that international childbirth intervention statistics indicate that we need to be “marching in the streets” for the protection of physiological birth? If we keep going in the current direction, it is possible that, it will be a race to see whether climate change or our inability to reproduce, without medical and technological assistance, causes the extinction of our species, first.

“What will be the effects of a weaker and weaker human oxytocin system? What is the future of love hormones? What is the future of humanity?” (Michel Odent)

In this edition we summarize the data in the 2017 Report on Maternity, specifically in terms of its impact on breastfeeding. Our analysis is (again) accompanied by statements from women who responded to the 2018 on-line survey. We thank them for their input.

MSCC welcomes new members to our Steering Group. Steering Group Meetings are held on the 2nd Tuesday of each month (except December & January). Meetings are held at Birthcare in Parnell and run from 10:00am – 12:00pm.

If you are interested in finding out more about the work of the MSCC or becoming a member of the Steering Group. Please email [email protected] or phone 022 4216008 to arrange to attend a meeting.

Report on Maternity 2017

https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/report-maternity-2017

In April, the Ministry of Health(MoH) published the long-awaited annual Report on Maternity for 2017. This is the first “annual” report, since the 2015 report which was published in July 2017. As far as MSCC is aware, there has been no explanation from the Ministry regarding the absence of a 2016 report. The MoH media release talks up the positive outcomes, i.e. fewer women smoking and a reduction in teenage pregnancies, but makes no comment about the ever increasing rates of medical interventions in pregnancy, the associated economic costs, the impact on the (already stretched) maternity workforce, or the physical and mental health outcomes for mother and baby, of this trend. In 2017, only 33.1% of women had a “normal birth” – a spontaneous vaginal birth without an induction, augmented labour, epidural or an episiotomy.(pg51) (Strangely, forceps and ventouse assisted births are absent from this definition so we can only assume that the “normal birth” statistic excludes women and babies who experienced this intervention.)

Women

In 2017, 59,661 women officially gave birth in NZ. “This equates to a birth rate (number of births as a proportion of females aged 15–44 years in the population) of 61.7 per 1,000 females of reproductive age: the lowest since 2008.”

The birthrate amongst teenaged women was slightly over 50% lower than in 2008 (from 33.8 (2008) to 15.0 (2017) per 1,000 women in this age group) with the total number of births to women in this age group being 2,309. The median age for women giving birth was 30 years old with nearly 60% of mothers being aged between 25 and 34 years old. The only age group in which there was an increased birth rate, was women over 40 years (15.0 (2008) to 16.2 (2017) per 1,000 women in this age group), with the total number of births for these women being 2,498 births.

Ethnicity

Women giving birth were predominantly European and aged 25–34 years.

| Ethnicity | Number | Median Age (years) | Birthrate (per 1,000 women 15 -44yrs) | |

| Maori | 14,892 | 26 | 90.6 | |

| NZ European & European | 26,599 | 31 | 50.9 | |

| Pasifika | 6,008 | 28 | 83.2 | |

| Asian (excl. Indian) | 6,826 | 32 | 60.6 | |

| Indian | 3,776 | 30 | ||

| Other | 1,549 | 31 | 50.9 | |

In NZ, approximately equal numbers of the total population reside in each of the 5 quintile groups. Deprivation quintiles range from 1(least deprived) to 5 (most deprived. 50.8% of women who gave birth in 2017 resided in more deprived neighbourhoods: (i.e. 28.5% resided in quintile 5 and 22.3% resided in quintile 4, while less than 14.8% of women giving birth resided in quintile 1 (the least deprived) neighbourhoods. Māori, Pasifika and Indian women were more likely to reside in more deprived neighbourhoods. 48.5% Māori mothers, 58.8% of Pasifika mothers & 31.9% of Indian women who birthed in 2017 resided in quintile 5 neighbourhoods.

In the last ten years the birth rate amongst women residing in quintile 1 & 2 (the least deprived) neighbourhoods has increased very slightly, while the birthrate for those in quintile 3-5 has continuously decreased, with the biggest decrease in birthrate occurring amongst women residing in quintile 4 & 5 neighbourhoods, i.e. those with the greatest level of deprivation.

Geographical Distribution

Whanganui (80.6), Northland (80.6) and Bay of Plenty (79.5) DHB regions has the highest birth rate while Auckland (42.3), Capital & Coast (48.6) and Southern DHB regions (53.1) had the lowest birth rate, per 1,000 women of childbearing age.

“Half of the DHB regions had lower birth rates in 2017 than in 2013 (Figure 10). The decrease in birth rates was statistically significant in Waitemata, Auckland, Counties Manukau, Taranaki, Capital and Coast and Nelson Marlborough DHB regions. The largest decrease was in Auckland DHB region (from 55.6 to 42.3 per 1,000 females of reproductive age). During this time birth rates significantly increased in Bay of Plenty DHB region. “ (pg18)

Parity – Number of births per woman

“Approximately 40% (22,709) of women who gave birth in 2017 did so for the first time. A further 33.7% had given birth once, 15.1% had given birth twice, and 10.7% had given birth at least three times previously. (Parity was unknown for 534 (0.9%) of women. This distribution remained fairly consistent between 2008 and 2017.” (pg21)

BMI & Smoking

Over half of women (54.8%) were considered to be overweight at registration with an LMC and 13.1% identified as smokers at this time. Of the 7,411 women who identified as smokers at registration, 4,981 (72.1) were still or again smoking at 2 weeks after they’d given birth.

Babies

There were 60.026 babies born in 2017, 51.2% of whom were male and 48.8% female. 28.6% of these babies were Maori. Half of the babies born in 2017 were born to women/families living in the neighbourhoods with the highest levels of deprivation – 13,254 (22.2%) in quintile 4 and 17,039 (28.6%) in quintile 5.

Gestation

90.6% of the 59.905 babies born with known gestation were born at “term” (between

37.0 and 41.6 weeks gestation. There was a statistically significant increase in the numbers of babies born at 38 – 39 weeks, probably driven by the increase in the percentage of women having their labours induced. The figures are not given but the graph (pg73) shows the percentage of babies born at 38 – 39 weeks in 2008 to be approximately 38.5% rising to approximately 47.5% in 2017.

Birthweight

“In 2017, the majority of live-born babies (91.5%) were within the normal weight range at birth (2.5–4.4 kg). A further 6.1% of babies were born with a low birthweight!(<2.5 kg) and 2.4% were born with a high birthweight (≥4.5 kg)The. average birthweight of babies born in 2017 was similar to previous years, at 3.41 kg. Male babies, on average, were heavier than female babies (3.46 kg and 3.35 kg, respectively).” (pg69)

Type of Lead Maternity Carer (LMC)

In 2017, 92.3% of women registered for primary maternity care with an LMC midwife, GP or obstetrician compared with 80.6% in 2008. 2.7% were registered with a DHB Community Team compared with 11.8% in 2008. (Data was unavailable for 5% of women in 2017.)

In 2017, 72.3% of women registered with a Lead Maternity Carer (LMC) during the first 13 weeks of their pregnancies compared with 50.7% in 2008. The percentage of women registering with an LMC during the first trimester was lowest amongst:

- women <20 year old – 47.8%

- Maori women – 55.2%

- Pasifika women – 35.5%

- women living in the quintile 5 (the most deprived) neighbourhoods – 51.9%

Unsurprisingly, registration with an LMC during the first trimester of pregnancy decreased with increasing parity (the number times a the woman had already given birth).

| Lead Maternity Carer Type | 2017 | ||

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Registered with LMC | 55,076 | 92.3 | |

| Midwife | 51,854 | 86.9 | |

| Obstetrician | 3,064 | 5.1 | |

| General Practitioner | 112 | 0.2 | |

| Other/Unknown | 46 | 0.1 | |

| Not registered with LMC* | 4,585 | 7.7 | |

| Total | 59,661 | 100.0 | |

* This number includes those women who registered with DHB primary maternity services, e.g. DHB caseload midwives, DHB primary midwifery teams and DHB shared care arrangements. Only seven of the twenty DHBs provided data (Northland, Waitemata, Auckland, Hawkes Bay, Hutt Valley, Capital & Coast and Taranaki) accounting for 1,602 of these women. 2.7 % of women were registered with a DHB primary maternity service (compared with 11.8% in 2008). It is probable that the majority of the remaining 5% of women, were in fact registered with a service provided by a DHB who has not provided data which changes considerably the number of women who appear not to have received pregnancy care.

| Type of Birth | Number | Percentage | |

| Spontaneous Vaginal Birth(SVB) | 36,955 | 62.7 | |

| Spontaneous vertex | 26,822 | 62.5 | |

| Spontaneous breech | 133 | 0.2 | |

| Assisted Birth | 5,581 | 9.5 | |

| Forceps only | 1,932 | 3.3 | |

| Vacuum/Ventouse Only | 3,547 | 6.0 | |

| Forceps and Vacuum | 13 | 0.0 | |

| Assisted breech | 57 | 0.1 | |

| Breech extraction | 32 | 0.1 | |

| Caesarean Section | 16,423 | 27.9 | |

| Emergency (in labour) c-section | 8,981 | 15.2 | |

| Elective (pre-booked) c-section | 7,442 | 12.6 | |

| Unknown | 702 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 58,959 | 100.0 | |

The percentage of women birthing vaginally continues to drop. In 2008, 68% of women had a spontaneous vaginal birth dropping to 62.7% in 2017 and we fully expect that the stats for 2018 and 2019 will show a further decline. Anyone with an interest in maternity in AotearoaNZ knows that the c-section rate continues to rise but it is both alarming and disappointing that the assisted birth rate also continues to rise (8.4% in 2008 to 9.5% in 2017). It would seem that the authors of this report are also concerned about the falling vaginal birth rate because nearly a page is dedicated to describing the benefits of spontaneous vaginal birth (SVB). SVB however, does not mean, physiological labour and birth. the authors note that the SVB rate includes “labour interventions such as induction or augmentation prior to delivery”. (pg41)

Normal Birth

In May an independent intergovernmental body representing 132 countries released a report entitled, “Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Services” that told us that 1,000,000 species face extinction if human societies do not change the way we live. MSCC believes that it is time to ”save” physiological birth from extinction, if the human race is to survive. Only one woman out of every three (33.1%) had a spontaneous vaginal birth without induction, augmentation, epidural, episiotomy or caesarean surgery in 2017. More distressing was the revelation that only 22.8% of first time mothers had a normal birth. We have adopted a culture of using resources if they are available to us, regardless of need or consequence. Logic would suggest that women from the most deprived neighbourhoods would be in most need of medical support during pregnancy and birth but, “The proportion of women having normal births was lowest for those in the least deprived neighbourhoods and highest for those in the most deprived neighbourhoods (28.8% of women in quintile 1 compared with 36.1% of women in quintile 5).” (pg52, our emphasis). The birthing culture in Auckland has resulted in the lowest proportion of normal births anywhere in the country, just 20.8%! This is not sustainable, either economically, or for the survival of our species.

Breech births

It is also disappointing that the vaginal breech birth rate is so low, 0.4% of all births.

Statistics tell us that at least 5% of babies are in a breech position at term (i.e.

approximately 3,000 babies per annum in NZ) and these statistics show that only a tiny number of these mothers and babies are supported to birth vaginally.

A few mothers chose and were supported by their maternity care providers to birth their breech babies vaginally. The percentage of spontaneous breech births rose slightly from 54.6% (2008) to 59.9% (2017) of all breech births, while the percentage of assisted breech births and breech extractions showed apparently random falls and rises resulting in no significant change between 2008 – 2017.

Caesarean Section

In 2017, 27.9% of women had a caesarean section. Both the emergency and elective c-section rates have continued to climb in the last decade. In 2017, 24.5% of first time mothers had an emergency (in labour) c-section and 6.7% had an elective c-section. 16.7% of women who had previously given birth at least once, had an elective repeat c-section. If a mother has had an emergency c-section for her first birth, she is much more likely to have an elective c-section for a subsequent birth. With the continuing increase in the primary emergency c-section rate, we can expect that the secondary elective rate will also continue to rise.

National and international statistics tell us that the huge increases in surgical birth are driven more by our beliefs about birth and the culture of individual maternity hospitals, than the safety and wellbeing of mothers and babies. Despite being a region of high socio-economic deprivation (and its attendant health deficits), Tairawhiti DHB had the lowest proportion of emergency c- sections, with an 8.5% emergency c-section rate, compared to Auckland DHB where the emergency c-section rate was 19.2%. Auckland DHB also had the highest percentage of elective c -sections (15.6%). Is it possible that women in the Tairawhiti DHB catchment are physiologically better adapted to giving birth than women in Auckland, resulting in this way lower emergency c-section rate?

MSCC has been reporting on the shameful lack of access to maternity services for many women residing in the Southern DHB, so it is unsurprising that this DHB has the second highest rate of elective c-sections (15.5%). The further women have to travel to access maternity services the more likely it is that they (usually at the recommendation of their care providers), will elect to have a c-section to avoid the possibility of giving birth en route to a distant hospital.

Induction of Labour

In a society that craves control and certainty and a maternity model that preys constantly on mother’s fears; Is my baby genetically normal? Am I young enough/too old, too fat/too unhealthy? Do I have diabetes? Should I eat this? What side do I sleep on? Is my baby growing at the right rate? What will happen if I catch something? Is my baby too big/ too small? etc etc; it’s hardly surprising that in 2017, 25.5% of women who laboured, (this figure does not include the 12.6% of women who had an elective c-section) sought or were persuaded to have their labours induced. A whopping 30.0% of first time mothers had their labours induced. Once again, women living in less deprived neighbourhoods had a higher rate of induction (27.4% in quintile 1) than those living in the most deprived neighbourhoods (24.8% in quintile 5), again demonstrating that social indicators have a greater influence on the uptake of labour interventions, than health indicators.

Epidural Pain Relief

In 2017, 26.6% of women who laboured had an epidural. Again, epidural use was higher in women from higher socio-economic backgrounds, 32.6% for those living in quintile 1 neighbourhoods, compared with 22% for women from quintile 5 neighbourhoods. Only 18% of Maori women had an epidural compared with, 21.8% for Pasifika women, 28.9% for Pakeha & European women, 32.9% for Asian women (excluding Indian) and 42.3% for Indian women. 41.5% of women in labour with their first baby had an epidural as did, 14.7% of women who had previously given birth.

Augmentation of Labour

In 2017, a total of 22.8% of women, excluding those who had an induction of labour, had their contractions augmented. 28.5% of women giving birth for the first time and 18.5% of women had already given birth had their labours augmented.

Instrument Assisted Births and Episiotomy

A small justification for the rise in the c-section rate might be, a reduction in forceps and ventouse assisted births and episiotomies. Instead we see an increase in both the instrument assisted birth rate (from 8.4% in 2008 to 9.5% in 2017) and an increase in the numbers of women given an episiotomy, (from 11.8% in 2008, to 15.9% in 2017). When the c-section rate and the episiotomy rate are combined, we see that 43.8% of women were surgically cut during the birthing process! Asian women are the most likely to have an episiotomy, (Indian women, 36.9%, other Asian, 30.8%) compared with 6.7% of Maori women had an episiotomy in 2017. Shockingly, 31.3% of first time mothers who birthed vaginally in 2017 were given an episiotomy!

Multiple Birth

The multiple birth rate has remained fairly static and comprises 1.3% – 1.6% of all births. In 2017, the majority of women carrying twins had an elective c-section

(39.3%) and 24.9% had an emergency (in labour) c- section. All 14 women with higher order multiples (triplets etc,) gave birth by c-section. The majority of women who are carrying twins are advised to have a preterm or early term c-section and this report does not make clear whether the 24.9% of women who had an emergency c-section intended to labour, or whether they established in labour prior to their scheduled c-section date. In 2017, only 23.4% of twin mothers had spontaneous vaginal births with a further 12.4% having a forceps or ventouse assisted birth.

Place of Birth

The vast majority of women gave birth at a maternity hospital. Approximately 86.7% gave birth at a secondary or tertiary facility, 10% at a primary birthing unit (PBU) and only 3.3% at home.

The numbers of women birthing in a tertiary facility increased from 42.8% in 2008 to 45.6% in 2017. During a decade when a growing body of research has quantified the benefits of giving birth in a primary environment and the Ministry and some DHBs have paid lip service to the advantages of primary birthing, the numbers of women accessing this option has dropped from 13.1% (2008) to 10.0% (2017).

The report notes that choice of place of birth reflects the options available locally, as much as women’s preference and clinical need.

“Among women giving birth at a maternity facility:

- In 2 of the 18 DHB regions with at least one primary facility, at least 20% of women gave birth at a primary facility: Waikato (29.0%) and Northland (20.3%).

- In 8 of the 15 DHB regions with at least one secondary facility, at least 90% of women gave birth at a secondary facility, the highest proportions being in Hawke’s Bay (95.9%) and Wairarapa (95.6%).

- In four of the six DHB regions with a tertiary facility, over 80% of women gave birth at a tertiary facility: Counties Manukau (88.8%), Auckland (88.1%), Capital & Coast (86.5%), and Canterbury (85.2%). Waikato and Southern DHB regions had smaller proportions of women giving birth at a tertiary facility (69.2% and 50.3%, respectively).”(pp63-64)

The high percentage of women choosing to birth in a primary facility in Hamilton probably reflects the fact that in this DHB there are 9 Primary Birthing Units (PBUs) (a combination of publicly and privately owned) throughout the region from Huntly Birthcare in the north, to Waihi Maternity Annex in the east and Taumarunui Hospital in the south, with the other six dotted in between, including two PBUs, Waterford and River Ridge on the west and eastern boundaries of urban Hamilton respectively. A further 3.7% of women residing in Waikato DHB chose to birth at home meaning that nearly 1:3 women in this region chose primary birth, with the result that only 69.2% of women birthed in the tertiary hospital – an outcome which probably saved, the DHB thousands of dollars and, more significantly, saved around 2,000 mothers and babies from exposure to unnecessary medical intervention during labour & birth.

Southern DHB covers the largest geographical area of any DHB in AotearoaNZ. Its secondary and tertiary hospitals, Invercargill and Dunedin are located on its eastern border. In 2017 there were seven primary maternity facilities in Otago-Southland locations; Oamaru, Alexander, Balclutha, Gore, Winton, Lumsden and Queenstown leaving whanau in the Wanaka and Te Anau areas with no option for access to either PBUs or Maternity Hospitals without first travelling for hours. Women in the urban Dunedin have no access to a PBU and the Winton PBU is approximately half an hour Norwest of Invercargill city centre. It is clear that this huge region needs more PBUs, as evidenced by recent reports of births in ambulances and a midwife’s consulting room, instead, since 2017, the DHB has closed PBU at Lumsden.

Home Birth

The percentage of women giving birth at home has fluctuated between 3% and 3.5% of all births for the past decade. In 2017, 3.9% of women planned a home birth with 3.4% giving birth at home.

Women living in the West Coast region had the highest proportion of home births(10.5%), followed by women living in Northland (7.7%), both areas where access to a maternity hospital or primary birthing unit has continued to involve travelling long distances in labour. In these areas, geographical isolation appears to have encouraged a culture and acceptance of birth as a physiological process, to become embedded.

The home birth rate in both the Nelson-Marlborough region (5.7%) and in the Wairarapa (5.6%) were also significantly above the national average. Two Auckland DHB regions, Auckland and Counties Manukau, recorded the lowest percentage of home births with just 1.6% and 1.1% respectively, of babies being born at home.

Breastfeeding

This report only records breastfeeding data for two weeks post birth and the statistics are alarming. In 2017, 69.3% of babies were exclusively breastfed, 8.5% were fully breastfed and 15.3% were partially breastfed, at two weeks after birth. The percentage of babies being exclusively or fully breastfed at two weeks old has decreased in almost every DHB region over the past five years. “This decrease was “significant for babies in Waitemata (from 81.1% to 79.7%), Waikato (from 80.3% to 77.1%), Lakes (from 82.5% to 77.7%), and Capital & Coast (from 80.9% to 77.6%) DHB regions.” (pg80). The only DHB to have maintained a reasonably high rate of breastfeeding (>84%) over the past 5 years is the West Coast DHB, with 87.1% being fully or exclusively breastfed at 2 weeks, in 2017.

Unlike the statistics for uptake of medical interventions during labour, it is more common for women in high decile neighbourhoods than low decile neighbourhoods to be giving their babies some breastmilk at 2 weeks old, (95.7% of babies in quintile 1 neighbourhoods compared with 90.5% in quintile 5 neighbourhoods). Maori women were the least likely to be exclusively or fully breastfeeding at 2 weeks (76.5%), while Pakeha and other European women were the most likely (81.6%). The percentage of babies continuing to be exclusively or fully breastfed after 2 weeks of age drops dramatically. (See article following.)

Handover of Care

“Of the women who registered with an LMC in 2017, the vast majority accepted referral to their GPs at LMC discharge (95.5%). Care for the majority of the babies was transferred to a Well Child/Tamariki Ora provider (97.6%).” (pg 82)

Unfortunately, transfer to GP and Well Child Provider is not recorded for mothers and babies who have received care through their DHB so these stats are incomplete. This report is also not able to tell us about which Well Child provider these babies were transferred to, however, we know that the biggest provider of Well Child services is Plunket.

Breastfeeding

What the stats say and don’t say… and what women say

The Report on Maternity 2017 tells us that only 77.8% of babies were exclusively or fully breastfed at 2 weeks old. The breastfeeding statistics published by Plunket are even more concerning.

| 2017 | Exclusive | Fully | Partial | Artificial |

| Breastfeeding @ 6 weeks | 52% | 11% | 23% | 15% |

| Breastfeeding @ 3 months | 48% | 11% | 20% | 21% |

| Breastfeeding @ 6 months | 21% | 8% | 40% | 31% |

https://www.plunket.org.nz/news-and-research/research-from-plunket/plunket-breastfeeding-data-analysis/annual-breastfeeding-statistics/

Castro et al (2017)[1], using data from the “Growing Up in New Zealand cohort of families, reported that 88% of babies were enrolled with Plunket to receive Well Child Services but that Maori and Pacific babies are under represented in Plunket enrolments. The 6,685 singleton babies with estimated due dates between 25 April 2009 to 25 March 2010) in the Growing Up in NZ cohort is more representative demographically accurate. In this analysis, 97% of mothers initiated breastfeeding with 66% of babies still receiving some breastmilk at 6 months.

The authors state that, “Breastfeeding practices are affected by historical, socioeconomic, cultural and individual factors. Improving breastfeeding practices requires supportive measures at different levels, including legal and policy directives, social support, women’s employment conditions, access to healthcare and healthcare provider knowledge and skills to support breastfeeding.” (pg41 Op. cit.)

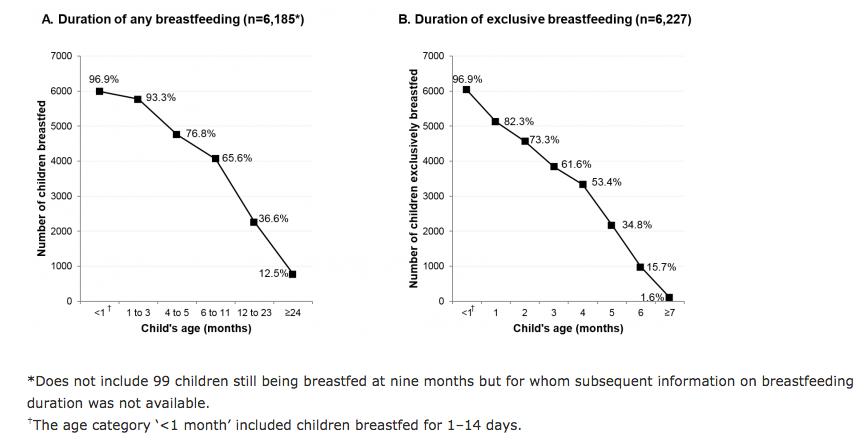

Marks et al (2018)[2] used the “Growing Up in New Zealand” study statistics to describe the relationship between the breastfeeding intentions of women and their partners and actual breastfeeding initiation and duration. Of the 6181 women who participated in this analysis 89% intended to fully breastfeed with a further 9% intending to combine breastfeeding with bottlefeeding. 68% of women intended to breastfeed (though not necessarily exclusively or fully) for >6 months and the graph (above) shows that 65.6% of babies were in fact, receiving some breastmilk at 6 months. The authors go on to state that, “although the global average percentage for exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) up to six months sits at 38%, EBF in developed countries is significantly lower and has not increased substantially despite several global initiatives (i.e., the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative).” In AotearoaNZ rate of EBF at 6 months in 2009/2010 was only 15.7%.

Does the birth experience of mothers and babies impact breastfeeding?

The rate and variety of interventions into labour and birth has been steadily rising at the same time that increasing evidence shows the negative impact of induction, augmentation of labour and active management of placental delivery with synthetic oxytocin, epidural anaesthesia, operative deliveries and caesarean delivery, on the establishment and duration of breastfeeding and the incidence of postnatal depression.[3][4][5]

Since the beginning of the 21st century research describing the physiological pathways by which these interventions interrupt maternal and infant behaviour and hormonal release in the critically sensitive period in the first hours and days after birth, has proliferated.[6][7][8]

Synthetic Oxytocin (SynOT)

Prolonged maternal and fetal exposure to synthetic oxytocin (SynOT), either for induction or augmentation of labour, has the potential for negatively impacting the initiation, establishment and duration of breastfeeding.[9][10] It decreases production of maternal endogenous oxytocin which weakens the maternal hormonal response to infant suckling and increases the risk of maternal anxiety during the early postnatal period. Newborn babies exposed to SynOT (which has been shown to cross into placental circulation and penetrate the fetal blood:brain barrier), demonstrate less organized pre-feeding behaviours and reflexes, as well as fewer periods of neonatal rest during postbirth skin-to-skin, which in turn, increases the risk of decreased newborn consolidation of memory regarding feeding cues, leading to ongoing issues with latching etc.[11][12]

Opiates

Opiates, in epidural anaesthetics and given postnatally for post c-section pain relief, can cross the placenta and enter maternal colostrum, potentially reducing the newborn baby’s muscle tone and depressing its reflexes and thereby, hindering the successful initiation of breastfeeding. Although some researchers have found that epidural anaesthesia containing fentanyl does not appear to negatively impact the initiation or duration of exclusive breastfeeding, others have found that breastfeeding success becomes compromised by higher doses and prolonged duration of maternal:fetal exposure to epidural during labour.[13][14][15] In addition, an epidural is always accompanied by intravenous fluids and often augmentation with SynOT.

Intravenous fluids

Intravenous fluids given during induction, augmentation, epidural anaesthetic and c-section have been shown to cause fluid retention in both mother and baby. Women who receive 2- 3L of fluid during the course of labour and those who have an IV left in for post-c-section pain relief, often experience swelling of the breast, nipple and areola making it difficult for the newborn baby to latch on. When the mother is given these quantities of fluid, the baby also retains fluid meaning it weighs more at birth. This makes it likely that, after peeing out this excess fluid, the baby will seem to lose >7-10% of his birth weight. This usually results in the recommendation that the baby be given formula top-ups, which in turn, can undermine the establishment of breastfeeding. A number of authors have suggested that babies of mothers who have prolonged intake of intravenous fluids are not weighed for the first time till 24 hours of age, or 24 hours after IV fluids have been discontinued.[16][17]

Caesarean Section

The rate and duration of breastfeeding are lower amongst women who have had caesarean-section compared with those who have birthed vaginally and lower again for women who have an elective c-section compared with those who have an emergency c-section.[18] More women who birth by c-section have problems establishing breastfeeding and stop breastfeeding sooner than women who have birthed vaginally. Limited immediate skin-to-skin duration, diminished postoperative mobility, postoperative pain, post-operative complications, pain relieving medication and a delay in the onset of lactation all potentially compromise the establishment of breastfeeding post c-section.[19][20][21][22]

The Report on Maternity (2017) does not aggregate interventions per woman, but it does tell us that 25.5% of women had their labours induced and an additional 22.8% had their labours augmented, (some of these women will also have had an epidural and an in-labour c-section). A further 12.6% of women had an elective c-section. In 2017, therefore, 60.9% of women who birthed in AotearoaNZ had at least one medical intervention that has been shown to negatively impact the successful initiation of breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding Support

Most women who experience medical interventions during labour and birth will need attentive and expert support and guidance to overcome the associated hormonal, physiological and physical impediments to the initiation and establishment of breastfeeding. Instead, successful breastfeeding appears to be further undermined by a chronic shortage of midwives and lactation consultants in our maternity hospitals.

“Breastfeeding support definitely needs improvement – I struggled for a long time when a lactation consultant could have helped (hospital midwives kept saying it’s fine…it wasn’t.) Undiagnosed tongue tie cut at 4 weeks by GP was the issue.”

(Tauranga)

“Breastfeeding support- I didn’t have any apart from getting lucky with one of the hospital nurses bringing me a feeding chair and pillow and a manual pump which didn’t work – at least she sat with me and guided me. I had no idea about anything and it was making me depressed feeling like I was failing my perfect baby – would be great if there was lactation support properly at hospitals … due to an infection from surgery I stayed in hospital for a week. Nobody guided me properly, they’d just have a look say,” she’s fine, if it hurts just take her off and latch again”. I know the nurses are very busy so it would be nice to have lactation staff around to help.”

( Middlemore 2017)

“I knew my baby was starving (not just regular new baby hungry) and they didn’t listen to me. I had undiagnosed low supply which no one picked up until my baby was admitted to the paediatric ward at 4 days old for jaundice and dehydration where I was seen by a lactation consultant. I felt that my (subsequent) choice to formula feed upset a lot of the midwifes – they provided me with little to no information regarding this”

(Wellington 2015)

“I needed more support post -natally in hospital with breastfeeding. No lactation consultants were available. Midwives gave me opposing advice. It was a mess. I got mastitis and gave up. Am now happily formula feeding.”

(Auckland 2018)

“Let’s not even mention the breastfeeding “help” for the first 4 days…my nipples were raw wounds but baby’s latch was “great”?!? I am medically trained, but as a new mum thought “what do I know” instead of trusting what I knew. Had I not had a good support network that whole experience would have probably left me with PND.

(Whanganui 2016)

“Post birth experience (five days) in hospital was horrific – no breastfeeding support, I didn’t know who was a nurse, a midwife, an orderly and was given conflicting (breastfeeding) advice by different people.”

(Auckland)

“…postnatal hospital care was awful and traumatic – understaffed and unable to support me with baby – ended up with feeding and psychological issues due to lack of care..”

(Wellington 2017)

“Postnatal care with hospital midwifes was poor. Wasn’t shown how to breastfeed or given any advice. Felt ignored. Need more breastfeeding support. Lactation consultation should be offered to all women struggling to breastfeed.”

(Hutt Hospital 2018)

“The first 24hours after giving birth (after my midwife had left) I didn’t have anyone check my breastfeeding latch properly and I got severe nipple damage. This was at Christchurch women’s. Once I got transferred to Ashburton maternity I got much better hands on support for breastfeeding. I had great support from all the staff at the primary birthing facility for those first few days after giving birth.”

(2017)

“The first night in hospital I was not allowed to have my partner stay as per policy and unfortunately nurses and midwives working were understaffed and very busy so there was not the time to support me with breastfeeding.”

(Wellington 2016)

“There was no lactation consultant available. A rotation of overstretched midwives and nurses giving different opinions had an adverse effect on our little one’s ability to feed. I feel continuity of care was compromised at this time and this should be improved.”

(Auckland 2017)

“Was disappointed with level of care in hospital postnatally again, felt like they were very busy, too busy to help and I wished we could have just gone straight home. Breastfeeding support was very poor. I wasn’t given any support in identifying and mitigating potential risk factors for low milk supply (of which there were many). Received constant conflicting advice from midwives and had to fight to get referral to LC.”

(Wellington 2018)

With my first baby in 2016 I ended up on postnatal ward on antibiotics and he got taken off me at birth. I got put into a 4 bed room without my baby with me (he was in NICU) so I felt very uncomfortable, stressed and upset being a first time mother and everything going on with baby and I had no support with me as they had to go home. The staff then brought him to me at 4am and said his next feed was due at 6am and left and I had no idea what I was doing or how to feed him until my midwife came the next day to see us and showed me!”

(Waikato 2016)

Fortunately some hospitals and Primary Birthing Units do appear to sometimes have sufficient numbers of caring midwives, with skills in assisting early breastfeeding.

“I got breastfeeding support from Helensville Birthing Centre and that was fantastic!! They made me feel so safe and no question was dumb.”

(2016)

“Breastfeeding support while in hospital, often by midwives in the middle of the night – and the flexibility to stay four nights until feeding was established. This was crucial to breastfeeding success.”

(Wellington 2018)

“I found the midwives very helpful with breastfeeding and they would often help me latch my baby as I was an anxious new mum not knowing what I was doing. I stayed in hospital for 5 nights and not once did they try rush me home. I feel very grateful for the kind care I received.”

(Gisborne 2017)

“I loved giving birth at St. George’s and then walking to my room to settle in! The food was amazing and the midwives were great at assisting with breastfeeding.”

(2016)

“I was advised to go to Warkworth birthing centre. The birthing centre is 5-star – like literally everything. I stayed for two nights and I was taught how to breastfeed properly…”

(2018)

“I went to Helensville birth centre and the ladies there were amazing. Always checking in on me and baby to see how we were going. The breastfeeding support was phenomenal.”

(2017)

“Lots of breastfeeding support from hospital staff and my midwives. Made a huge difference to my successful breastfeeding journey.

(Hawkes Bay 2016)

“Loved Papakura birthing unit! And the breastfeeding support there.”

(2017)

“My midwife was amazing, and I was Kawakawa hospital (rural) so there weren’t many women giving birth there. I didn’t feel pressured to leave early or anything. I stayed for a couple of days. They were also really supportive and helpful with breastfeeding.”

(2017)

“ Really liked the support at Kenepuru hospital, I received loads of breastfeeding help over the two days I was there.”

(2017)

“Te Awamutu Birthing was a phenomenal birthing centre to birth at (both times), breast feeding support was fantastic.”

“The breastfeeding support I received in hospital was fantastic and gave me the confidence to go home and successfully feed my baby.”

(Dunedin 2017)

“The postnatal care on the ward was great. I found the midwives very helpful with breastfeeding and they would often help me latch my baby as I was an anxious new mum not knowing what I was doing. I stayed in hospital for 5 nights and not once did they try rush me home. I feel very grateful for the kind care I received.”

(Gisborne 2017)

“The care in Nelson hospital was great, lots of support from midwives during my 5 day stay. Breastfeeding support was most appreciated and everyone had a positive attitude towards helping me and my baby to learn. I felt very well looked after and important.”

(2017)

“The midwives at Warkworth birthing unit were amazing during our postnatal stay, being so supportive and encouraging while I was trying to get the hang of breastfeeding.”

(2017)

“We birthed at St George’s, the care of the team there was caring. I didn’t feel like just a number as I had during my previous experience at our main woman’s hospital. The staff never made you feel like you were annoying them for anything that we needed help with especially breastfeeding.”

(2018)

“We were supported by a range of midwives and no question was too dumb to ask. We had 6 days on the ward with massive breastfeeding support. I couldn’t have delivered and cared for my twins without the support offered.

(Auckland 2018)

Postnatal Transfer and Early Discharge

The initiation and establishment of breastfeeding is often interrupted by early transfer to a Primary Birthing Unit (PBU) that disrupts maternal hormones during the crucial first hours after birth, and/or early discharge policies that see women sent home before breastfeeding is established. It is a tragedy that more women are not encouraged to birth at PBUs, as this would reduce their exposure to both medical interventions in labour and the need to travel during the early postnatal period.

“More support in making sure good feeding is established before you are discharged from the hospital. Most women 3- 5 days minimum and some up to two weeks to help with breastfeeding. Some mums might rather be at home. But rest after giving birth and help by the nurses, an opportunity to sleep and heal and have milk supply established through good food and any other help would be great.”

(2018)

“ I think more time in the birthing unit after baby is born would be better. I didn’t feel like I had gained enough skills to breastfeed my 1st born before I had to leave and go home. 48 hours isn’t long enough in most cases.”

(2016)

“Mums get pushed out of maternity wards way too quick and it causes issues especially if feeding hasn’t yet been established. More staffing is needed to support new parents.”

(Capital and Coast DHB 2016)

“Finally once we arrived in Huntly the midwife helped me feed my baby….who really struggled to latch.

We then spent the next 2 days expressing and feeding baby by syringe because she couldn’t latch. I was told “you don’t need formula” 2 days stay then it was time to leave……. sent home with a baby that I couldn’t even feed!.”

(2017)

“I stopped breastfeeding earlier than I would have liked because I wasn’t shown how to get baby to latch properly. I felt like they didn’t really want to help and wanted me to just do:know everything already. Would have been nice to stay longer, ideally after baby blues have passed.”

(Dunedin 2017)

“In general, I had great support at the hospital with a midwife really taking the time and helping me breastfeed as I had problems but I also experienced a nurse at the hospital that was eager at trying to get me out of the hospital even though I couldn’t feed my baby as my milk hadn’t come in. I would up the staff numbers, as there were nights when they were understaffed and couldn’t be everywhere at once.”

(Taranaki 2018)

“The Taumarunui maternity ward is very understaffed, the midwife wasn’t able to spend much time with me because of this. There are no lactation consultants, I had to travel 2hrs to see one and again to have tongue tie assessed.

(Taumarunui 2017)

“The worst part for me was being discharged and sent to Kenepuru from Wellington within a couple of hours after birth after 3 nights of no sleep. I couldn’t walk and nobody seemed to care. The midwives at Kenepuru treated me like I was an inconvenience and in the way and I tried not to bother them. The fear at being left alone with a baby I had no idea how to care for was overwhelming. Nobody seemed to ask me if I was ok. My baby screamed the entire night because she was clearly hungry and I didn’t know how often she needed to be breastfed. Nobody seemed to care. Was a lonely terrifying time for me and I believe my experience contributed to anxiety attacks I had afterward.”

(2017)

The application of “Hands on” breastfeeding procedures

We were alarmed by the number of women who reported that they had been exposed to “Hands On” procedures, usually without warning or consent. For decades, studies have shown that women who are exposed to this type of breastfeeding “help” are less likely to continue breastfeeding than women who are supported by “hands off” assistance and techniques e.g. dolls, artificial breasts.[23][24][25] Palmer et al (2012)[26] describes the harms of this practice. Hands -on breast touch almost always involves women feeling forced to give access to her body. Even when a woman is asked, she often feels obliged to endure this unhelpful procedure for her baby’s sake. Already upset by her apparent inability to feed her baby, appalled at the prospect of a stranger handling her breasts, but desperate to feed her baby. These emotions and those triggered by her baby’s crying and/or refuse signals, often leaves the mother in such emotional turmoil that she is not able to tap into her instinctive understandings of, and responses to, her baby. There is no evidence that mothers “learn” from “hands-on procedures” how to latch the baby themselves. Even if the baby is latched on and feeds the mother’s confidence is often further undermined, she is left feeling angry, abused, disconnected from her baby and dissociated from her body, making breastfeeding even more difficult.

“A hospital midwife tried to force formula on our newborn for blood sugar reasons even though he was nursing well. She tried to scare my husband off of the idea of donor colostrum in the event breastfeeding wasn’t enough…. after having tried to force formula on our 1 day old baby she then forced hand expressed milk with her assistance. That part was quite upsetting.”

(2016)

“Also one hospital midwife transposed the numbers of when my baby was born with my first baby. So the new shift on thought she wasn’t feeding enough and got a lactation consultant who was quite rough and shoved my boob at my babies face. If it had been my second or third I would not have allowed that but being my first and less than 12 hours after giving birth I was in a bit of a haze.”

(Dunedin)

“Breastfeeding support was lacking -squishing a woman’s breast into the baby’s mouth and suffocating the baby with it is not “supporting breastfeeding”, neither is squeezing a nipple and saying “oh you haven’t got any milk” when your baby is hours old.”

(Christchurch)

“Hospital care was good the first time as I had a PPH, but the nurses who were “helping” with breastfeeding for the first time were rude and forceful, ie. pulling my top down without asking me, not being polite or respectful of privacy.”

“I was transferred hospitals at 1am, starving and exhausted. I immediately had a lactation consultant on me, grabbing my boob squeezing it, ramming baby’s head against me, telling me I was doing it wrong. When I asked for a 5min break to have a cup of tea or something she so no and that I had to get this right first. I was so demoralised I asked for formula. We continued our breastfeeding journey at home without aggressive intervention.”

“It was also strange and unexpected to have nurses grabbing your boob and jamming it into the baby’s mouth. I know it is part of their job every single shift of every working day to assist with establishing breastfeeding but for an enormous percentage of their patients it is their first baby and the entire experience is foreign to them. So to have someone do this (and it was more than once with each baby) was beyond awkward and somewhat upsetting.”

(Christchurch)

“The hospital midwives were rude and were extremely rough when forcing my nipple into my baby’s mouth. I wrote a complaint up and sent it to them but never heard back.”

(Waikato 2016)

“There were two nurses at the hospital who I felt didn’t treat me with respect e.g. grabbing my breast without permission to get baby to feed.”

(Waitakere 2016)

According to the Growing Up in NZ study 89% of new mothers intend to fully breastfeed. However, the New Zealand Breastfeeding Authority’s data for breastfeeding rate at discharge from all maternity facilities in 2017 was 79.8% and Plunket statistics for 2017 (above) show, that by 6 weeks of age, only 53% of mother:baby pairs were still fully breastfeeding. It is unlikely that such a high number of mothers who intended to fully breastfeed simply decided, to stop breastfeeding their babies within 6 weeks. It is much more likely, given our labour and birthing intervention statistics, that extremely patchy inpatient postnatal care and a flawed service specification and payment structure for the postnatal module of LMC care, resulted in an inadequate level of breastfeeding support for many mothers. The structure of, and payment for, postnatal care provision, results in too few women receiving the timely, predictable and face-to-face breastfeeding support in the early postnatal period that the evidence shows is essential to get breastfeeding off to a good start.[27] Insufficient support to overcome the intrapartum and early postnatal obstacles to breastfeeding that our model of birthing care, puts in women’s way, results in breastfeeding difficulties that are often so physically and/or emotionally painful that the mother becomes overwhelmed and depressed. When breastfeeding difficulties are not resolved in a timely fashion, the early mothering experience can be robbed of a lot of joy. Women often experience physical pain as well as feelings of sadness, failure, inadequacy, anger and guilt when they cannot happily and comfortably breastfeed their babies.

“Although I was given a lot of great help with breastfeeding, which was fantastic, once I decided to bottle/formula feed because of supply and latching issues the support disappeared – there isn’t a lot of information on formula feeding out there. More information on tongue ties and faster treatment for tongue ties would be great, we had to wait 7 weeks for treatment and waiting that long had a big effect on our feeding situation.”

(2018)

“BEST was the support on the ward to establish breastfeeding AND provide formula so that my baby had the energy to initiate breastfeeding when it finally happened. There is a pervasive culture glorifying the ‘naturalness’ of birthing and breastfeeding. I am a militant breastfeeder now – but without formula in those first few days my daughter wouldn’t have had the energy to learn how to nurse after our awful labour and birth. After 5 day’s of labour, we were both exhausted. She didn’t latch at all until day 4, despite being assigned lactation specialists on the maternity ward. We haven’t needed any help since we got home, but those first four days were excruciating for me emotionally, as I felt I had failed my daughter right off the bat because we had allowed her to be given formula.”

(Palmerston North 2017)

“Breast feeding support could be better. I nearly gave up after all the confusion from conflicting advice from different nurses, midwives and lactation consultants. I was fortunate as I was able to afford to see a lactation specialist, without that appointment I’d probably be formula feeding my son.”

(2018)

“I needed so much more support with breastfeeding. I saw the Plunket LC and that was helpful to a point but it’s so hard to figure out the right approach to take when there has been a complication and your supply is low and you get different info from different people. To this end, there HAS to be a change in the way supplementary feeding is handled. I wanted to exclusively breastfeed but I literally didn’t have enough milk due to retained products of conception. While I was suggested to ‘top him up’ there was not enough information about how to actually go about doing this. Thank god I have a phone and an internet connection so that I could research it myself. There is an impression that it’s breast OR bottle and we all know ‘breast is best’… that is until your baby is not gaining weight!! For those of us who legitimately have a medical issue causing a complication to milk supply there should be a wraparound service for ongoing support that works better than what’s in place. While seeing an LC once a week is great, that’s ONE feed out of 10- 12 a day for weeks. If the powers that be want us to breastfeed because it’s ‘best’ then give us more support.”

(Auckland 2018)

“I suffered 3 excruciating months breastfeeding my first baby with a tongue tie that resulted in cracked, bleeding nipples and every feed hurting me so I started to dread them. I asked several times for help but they all said it was my latch. It was only when I went to a community run breastfeeding support group that a gp and a lactation consultant suggested that my baby had a tongue tie – I promptly burst into tears of relief. It took nearly another month to get my baby’s tongue tie lasered. If only the midwives in the hospital had been able to identify the problem, I would have only suffered for a month or so, instead of three.”

“I think formula feeding, although apparently not the best for a baby, needs to be supported as much as breastfeeding. I couldn’t produce enough milk for my daughter and was made to feel like shit by one particular midwife about topping up with formula. I honestly only cried after birth due to my struggles with breastfeeding.”

(Balclutha 2018)

“Our baby had a tongue tie. Getting treatment for that was totally up to us seeking out support and paying privately. If breastfeeding is to succeed then better knowledge and systems around this are necessary.”

(2016)

“When I had trouble breastfeeding I accessed all the support but NO ONE attributed my problems or my child’s problems to a lack of supply. I found myself ill-prepared as a first time mother. The stress was unbearable especially as I battled with feeling like a failure. I had to invest in professional help through a Paediatric specialist who determined my 4 month old was underfed Heartbreaking. I was set up to fail with a lack of information and appropriate support.”

(2016)

The dual mantras of “evidence-based practice” and “breast is best” are frequently proclaimed by our health authorities, maternity facility managers and individual maternity practitioners. Our statistics show us that neither is currently being facilitated or achieved throughout most of AotearoaNZ. The combination of ever-rising rates of unnecessary interventions in labour coupled with serious gaps in postnatal care and support, undermines the ability of women to provide their babies with the undisputed, short and long term, benefits of being exclusively breastfed. As one mother (above) said, “If the powers that be want us to breastfeed because it’s ‘best’ then give us more support.” (Auckland 2018)

References

| ↑1 | Castro T, Grant C, Wall C, et al. Breastfeeding indicators among a nationally representative multi-ethnic sample of New Zealand children. NZ Med J.2017;130(1466):34-44 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Marks EJ, Grant CC, de Castro TG et al. Agreement between Future Parents on Infant Feeding Intentions and Its Association with Breastfeeding Duration: Results from the Growing Up in New Zealand Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6): doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061230. |

| ↑3, ↑18 | Hobbs AJ, Mannion CA, McDonald SW et al. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016;16(90): |

| ↑4 | Henderson JJ, Dickinson JE, Evans SF, McDonald SJ, Paech MJ. Impact of intrapartum epidural analgesia on breast-feeding duration. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003 Oct;43(5):372–7. pmid:14717315 |

| ↑5 | Dozier AM, Howard CR, Brownell EA, et al. Labor epidural anesthesia, obstetric factors and breastfeeding cessation. Matern Child Health J 2013;17(4):689–698 |

| ↑6 | Cadwell K and Brimdyr K. Intrapartum Administration of Synthetic Oxytocin and Downstream Effects on Breastfeeding: Elucidating Physiologic Pathways. Ann Nurs Res Pract. 2017; 2(3): |

| ↑7 | Lothian JA. The birth of a breastfeeding baby and mother. J Perinat Educ. 2005 Winter;14(1):42-5. doi: 10.1624/105812405X23667. PubMed PMID: 17273421; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1595228. |

| ↑8 | Kujawa-Myles S, Noel-Weiss J, Dunn S et al. Maternal intravenous fluids and postpartum breast changes: a pilot observational study. Int Breastfeed J. 2015; 10(18): doi: 10.1186/s13006-015-0043-8 |

| ↑9 | Gu V, Feeley N, Gold I et al. Intrapartum Synthetic Oxytocin and Its Effects on Maternal Well-Being at 2 Months Postpartum. Birth. 2016; 43(1): 28-35 |

| ↑10 | Bai DL, Wu KM, Tarrant M. Association between intrapartum interventions and breastfeeding duration. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2013;58(1):25-32. |

| ↑11 | Brimdyr K, Cadwell K, Widstrom A et al. The association between common labor drugs and suckling when skin‐to‐skin during the first hour after birth. Birth 2015;42(4):319-328. doi: 10.1111/birt.12186 |

| ↑12 | Olza Fernández I, Gabriel MM, Malalana Martinez A, et al. Newborn feeding behaviour depressed by intrapartum oxytocin: A pilot study. Acta Paediatr 2012;101(7):749–754. |

| ↑13 | Jordan S, Emery S, Bradshaw C, Watkins A, Friswell W. The impact of intrapartum analgesia on infant feeding. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 2005;112(7):927–934. |

| ↑14 | Y. Beilin, C. Bodian, J. Weiser et al. Effect of labor epidural analgesia with and without fentanyl on infant breast-feeding: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Anesthesiology 2005; 103(6):1211-1217 |

| ↑15 | Moisés EC, de Barros Duarte L, de Carvalho Cavalli R, et al. Pharmacokinetics and transplacental distribution of fentanyl in epidural anesthesia for normal pregnant women Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005;61(7):517–522 |

| ↑16 | Noel-Weiss J, Woodend AK, Peterson WE, Gibb W & Groll DL. An observational study of associations among maternal fluids during parturition, neonatal output, and breastfed newborn weight loss. Intl Breastfeed J 2011; 6(9). doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-6-9 |

| ↑17 | Deng X & McLaren M. Using 24-hour weight as reference for weight loss calculation reduces supplementation and promotes exclusive breastfeeding in infants born by cesarean section. Breastfeed Med. 2018 Mar;13(2):128-134 |

| ↑19 | Evans KC, Evans RG, Royal R et al. Effect of caesarean section on breast milk transfer to the normal term newborn over the first week of life. Arch Disease in Childhood – Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2003;88:380-382. |

| ↑20 | Zanardo V, Svegliado G, Cavallin F et al. Elective caesarean delivery: does it have a negative effect on breastfeeding? Birth. 2010;37(4):275-9. |

| ↑21 | Stevens J, Schmied V, Burns E, Dahlen H. Immediate or early skin-to-skin contact after caesarean section: a review of the literature. Matern Child Nutr. 2014 Oct;10(4):456-73. |

| ↑22 | ZanardoV, Pigozzo A, Wainer G et al. Early lactation failure and formula adoption after elective caesarean delivery: cohort study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatl Ed. 2013; 98(1):F37–F41. |

| ↑23 | Ingram J, Johnson D, Greenwood R. Breastfeeding in Bristol: teaching good positioning, and support from fathers and families. Midwifery. 2002;18(2):87–101 |

| ↑24 | Fletcher D, Harris H. The implementation of the HOT program at the Royal Women’s Hospital. Breastfeed Rev. 2000;8(1):19–23 |

| ↑25 | Inch S, Law S & Wallace L. Hands off! The breastfeeding best start project . Pract Midwife 2003; 6(10):17-19. |

| ↑26 | Palmér L, Carlsson G, Mollberg M, Nyström M (2012) Severe breastfeeding difficulties: Existential lostness as a mother—Women’s lived experiences of initiating breastfeeding under severe difficulties, Int J. Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 2012; 7:1, DOI: 10.3402/qhw.v7i0.10846 |

| ↑27 | Enabling breastfeeding for mothers and babies Cochrane Special Collections (2017) https://www.cochranelibrary.com/collections/doi/10.1002/14651858.SC000027/full |