WELCOME, TENA KOUTOU KATOA, KIA ORANA, TALOFA LAVA, MALO LELEI, FAKAALOFA ATU.

- Women’s assessments of their ‘inpatient’ postnatal care

- In-patient postnatal care – does it exist in our hospitals?

- Shared rooms postnatally do not meet new mother’s needs.

- We’ve just become a family – postnatal care should accommodate fathers/partners too.

- I was discharged before I was ready.

- Primary Birthing Units much better at meeting the needs of new mothers and babies

- It’s not over yet…

- Southern District Health Board Announces Closure of Lumsden Maternity Unit.

- Mind that Child, A Medical Memoir

- Research: Intrapartum Administration of Synthetic Oxytocin and Downstream Effects on Breastfeeding: Elucidating Physiologic Pathways.

MSCC recently co- sponsored an online consumer questionnaire asking women to evaluate their maternity care experience. In this edition of the newsletter, we have chosen to focus on the information shared about their postnatal experiences. Most women who had birthed in a Primary Birthing Unit (PBU) or who had been transferred to a PBU were very satisfied with their experience and grateful for the care they received. We were therefore, disappointed and sad to hear the public announcement in August, of the Southern District Health Board’s decision to close Lumsden Maternity Unit. We provide some background to this decision and discuss the issue of the closure of existing PBUs like Lumsden in this edition.

In July Auckland Paediatrician, Dr Simon Rowley, published a memoir of his experience of, mainly paediatric medicine, since his graduation in the 1970s. We review his book along with a critique of some of his conclusions in this edition.

Finally, following up on our review of Michel Odent’s book, “Childbirth in the Age of Plastics’ in our May newsletter, we share a recent research paper looking at the effects that synthetic oxytocin administration during labour has on breastfeeding outcomes.

We hope that you are informed and challenged by this edition of our newsletter.

Women’s assessments of their ‘inpatient’ postnatal care

In June, the MSCC received an invitation from the Ministry of Health (MoH) to attend a Maternity Whole of System Workshop in Wellington in mid- July. Unfortunately the MoH was not offering any assistance with travel (and had sent the invitations out too late for us to book budget priced airfares), so MSCC was unable to send delegates. Our colleagues from Women’s Health Action (WHA), however, decided to attend to represent maternity consumers and to assist with this, they put together a questionnaire asking women/whanau who had birthed in NZ in the past 10 years to assess the services they received. WHA invited the MSCC, MAMA Maternity and La Leche League to co-sponsor the questionnaire which was circulated via our social media platforms. More than 1000 women aged between 18 and 54, who gave birth at home, in Primary Birthing Units (PBU) or Hospitals, from throughout NZ/Aotearoa responded.

Much valuable (and shocking) information about women’s experiences of maternity care was generously shared by respondents. We have chosen to focus on the information shared about their immediate postnatal experiences in hospital and/or in the birthing unit in this edition of our newsletter coming out as it is, following news of the closure of yet another PBU.

In recent editions of our newsletter we have shared our concerns about the continually rising rates of intervention during pregnancy, labour and birth. It seems to us that our MoH and DHBs have access to a bottomless pit of funding for antenatal testing and screening as well as labour and birthing interventions, but that postnatal care has become increasingly under-resourced. Postnatal care is almost exclusively women (midwives) providing care for women, so is it no surprise that this is the least resourced module (unless of course there is a need for neonatal intensive care – in which case, resources are found). After a labour and birth that more often than not has involved synthetic hormones, medical pain relief and/or, major abdominal surgery, a new mother is given a few days of inpatient postnatal care, then sent home to recover physically and emotionally, establish breastfeeding and learn how to mother her child with only intermittent funded visits from a postnatal midwife and mostly, inadequate and/or delayed access to any funded ancillary services to treat breastfeeding, mental health or physical recovery problems. It is clear, that the funding and organisation of postnatal care has remained the “Cinderella” of the maternity system when arguably, the transition to mothering and the transition of the baby into the “outside world, is the

most crucial component of maternity care, impacting as it does, the future mental and physical health and wellbeing of both mother and baby.

Firstly, some baseline statistical information about the respondents, their LMCs and their place of birthing.

| Maternity Consumer Evaluation of Care. July 2018 | |||

| Age | Response | Place of birth | |

| 12 – 17 | 2 (0.18%) | Home | 144 (12.63%) |

| 18 –24 | 63 (5.52%) | Birthing Unit | 91 (7.98%) |

| 25 – 34 | 656 (57.49%) | Hospital | 878 (77.02%) |

| 35 – 44 | 393 (34.44%) | Other | 1 (0.9%) |

| 45 –54+ | 27 (2.37%) | Not Stated | 21 (1.84%) |

| Total | 1141 | Total | 1135 |

| Ethnicity | LMC | ||

| Maori | 61 (5.35%) | Midwife | 970 (85.09%) |

| NZ Euro | 886(77.72%) | Obstetrician | 42 (3.68%) |

| Pasifika | 10 (0.89%) | Combined MW/Ob or GP/HospTeam | 115 (10.09%) |

| Asian | 22(1.93%) | Other | 13 (1.14%) |

| MiddleEastern | 1 (0.09%) | Total | 1140 |

| Latina | 6 (0.53%) | ||

| Australian | 16 (1.40%) | Overall satisfaction | |

| European | 69 (6.05%) | Very satisfied | 620 (54.39%) |

| Filipina | 5 (0.44%) | Satisfied | 337 (29.56%) |

| Other | 64 (5.61%) | Neutral | 71 (6.23%) |

| Total | 1140 | Dissatisfied | 88 (7.72%) |

| Very dissatisfied24 | (2.11%) | ||

| Total | 1140 | ||

The majority of respondents were happy with their overall maternity care experience, but many experienced deficiencies in care, especially postnatally. Although respondents were relating their personal experiences and perceptions, their responses revealed that the deficits in service are pretty similar throughout the country.

In-patient postnatal care – does it exist in our hospitals?

Most of the respondents had given birth in a hospital, some were rapidly discharged to a primary facility but many stayed in a hospital postnatal ward because they had birthed by c-section or experienced other complications. Huge numbers of respondents experienced inadequate and sometimes abusive, inpatient postnatal care. It seems as though some of our bigger hospitals are attempting to save money by understaffing and underfunding their postnatal wards and, discharging mothers and babies as soon as possible after they have given birth, with reckless disregard for the health impacts of these policies. Many of the comments also indicate that the midwives (and nurses) on the postnatal wards are suffering from ‘burn out’ and this is having a hugely negative impact on the health and wellbeing of mothers, most of whom, if they are in hospital postnatally, are coping with pain and lack of mobility after c-section surgery or the stress of having unwell or preterm babies in neonatal intensive care. District Health Boards and hospitals have never consulted women to find out what their needs are for their immediate postnatal care. The resourcing of hospital-based inpatient postnatal services seems to completely ignore the fact that the medical management of birthing in our hospitals is creating greater complexity for mothers and babies postnatally or that a growing body of research shows that the wellbeing of mother and baby requires a quiet, stress free, supportive environment and that the new family need to be together in the immediate postbirth days.

(I have included the name of the hospital where this was provided to demonstrate that the issues are nationwide. This does not indicate that un – named hospitals provide better care. The comments published are just a sample of the many similar comments we received. -ed.)

“…the nurses were so busy that

(North Shore Hospital)not one could spend a length of time with me to get it (breastfeeding) right as afirst time mother”

(Hospital) “Lactation Consultant…(responded) in an annoyed tone was that she was so busy and all booked up and that I would need my midwife to sort it out….”

“Hospital midwives were run-off their feet and would often forget to bring pain meds etc requiring multiple requests.” (Wellington Hospital)

(Dunedin Hospital)

“Over night there was 1 midwife and a student (on staff). Pain meds weren’t given on time as staff were rushed. When calling for assistance it would take 30 mins for anyone to arrive, during the days were better…”

“I have had a very dear friend unable to meet her baby for 10 hours due to staffing shortages. No one was available to take her to see her baby in NICU! This is disgusting and distressing especially as she was laying there surrounded by skin to skin posters! Staffing fatigue and shortages need to be addressed!!!”

“The first 24 hours were terrible, being put into a noisy shared postnatal room with nowhere for my husband to comfortably sit or rest after being up for 20 hours by the time we got there… nurses being too busy to bring painkillers on time… Too many visits at all hours by different specialists, very disruptive and I can’t remember most of the visits because (I) was so tired. All issues could be solved with better funding!.”

“Wellington Hospital maternity ward is awful. Too busy, not enough staff. I went to the ward at 11.30pm into a double room, my husband was kicked out straight away and I was terrified. I couldn’t feed properly & one midwife came (after me ringing the buzzer & waiting for such a long time) and told me to “have fun with it”. Absolutely ridiculous. I was left on my own in tears.”

“Wellington hospital postnatal care – I had to transfer here after baby was born in Kapiti as I had torn. The bed in my room didn’t even have a mattress or sheet for my baby. No support for first time mother here.”

“I would improve the hospital experience, more nurses/midwives to improve the quality of care for mothers and baby’s. After my emergency cesarean I wasn’t even taken to see my son in the NICU for 4 hours after he was born partly due to nurses being short staffed.”

“Please do not pressure women into any set time frame for recovery. Some may feel up to leaving hospital or walking etc soon and some may take some time. Everyone is different – we don’t all have the same recovery, please be compassionate and remember that although you see so many women who have cesareans, it’s OUR cesarean and it’s scary and it’s painful. It was like having a cesarean was so routine that no one cared about my pain levels. I didn’t get regular pain relief and felt pressured into pretending I had less pain that I did because I ‘should’ have less pain. It was a very disempowering experience.”

“I felt that there seemed to be too few midwives on at any one time at the hospital I gave birth in, (although they were all very attentive and helpful.) It seems like it’s an underfunded area of NZ’s Public Health system.”

(North Shore Hospital)

“I understand hospitals have to prioritise those in serious need of emergency care but I didn’t expect the ‘fend for yourself’ culture.”

“…my stay in hospital was pretty upsetting, I felt like I was a burden and a lot of the nurses were very rough with me and said horrible things which I found

upsetting at such a vulnerable time. It was very, very clear they were understaffed and a lot of the nurses just didn’t give a shit about you.”

“The care at the hospital in Greymouth was awful. Staff constantly tried giving me medicine I’m allergic too. Staff didn’t listen or believe me when I told them … I was told I needed to wake my child by a nurse to make sure he wasn’t dead. Awful experience from this hospital and its staff”

“The hospital maternity staff (with the exception of SCBU staff) were consistently unhelpful, dismissive, unsupportive and at times hurtful. My PND was made far worse and breastfeeding became a source of significant fear and anxiety due to the unpleasant post birth care.”

“I had a

(Taranaki Base Hospital)high risk pregnancy which resulted in my baby being born at 32 weeks. Afterbaby was born my care was non-existent – even though I … waspost c-section .”

“My midwife was wonderful, however we were treated badly at the hospital and had to wait 13 hours for stitches and I was left to dehydrate (Transferred from BU to hosp). More staff (needed) at the hospital.”

“Hospital staff were stressed and stretched, I often received conflicting advice and just didn’t really feel supported or cared about.”

“The hospital midwives were rude and were extremely rough when forcing my nipple into my baby’s mouth. I wrote a complaint up and sent it to them but never heard back.”

(Waikato Hospital)

“Was left for 12 hours post c-section laying in my own blood after I bleed a lot. … Also at Chch Women’s Hospital there is ongoing politics between private Obstetricians and some hospital staff… day 3 post surgery I was left without any pain relief because hospital staff were of the attitude that it wasn’t their job to see to my pain meds because I had been under private care…”

“Hospital was very obviously underfunded. Needs more midwives and beds.”

(Auckland City Hospital)

“Hospital staffing levels at Dunedin Hospital were way too low. Staff were clearly overworked.”

“Postnatal midwives in hospital were too busy to help most of the time. Postnatal ward needs more staff so they can help with breastfeeding. Taranaki Base Hospital maternity unit needs upgrading.”

“I did not feel there were enough nurses on staff and did not receive the best care as a result. The nurses did their best with their limited staffing. No one was able to assist me with a shower for almost 24 hours

(Hawkes Bay Hospital)post birth …I would have benefited from seeing a lactation consultant in hospital and ended up paying privately for one when I was home.”

“The hospital needs more midwives. I had UTI post natal so I was back at (readmitted to) maternity ward with baby. My fever was extremely high I could barely stand up due to the pain. (A) midwife assured me that I can get help changing baby’s nappy at night especially because I can’t fully bend both arms as they have IVs on the corner where I bend it. But next shift the midwife was so grumpy, she told me she was only going to do it once because she was busy and I have to do it myself! I was fainting, in and out of consciousness due to the high fever and she couldn’t care less about whether I die with my baby or not. Thank God after 8 gruelling hours of her shift, the next midwife was heaven-sent.”

“I had a c section and no pain relief was charted for afterwards, it took 8 hours to get anything other than paracetamol

(Christchurch Women’s)post op . The hospital wasshort staffed and no one brought in a bassinet, forcing me to hold my baby all night and not sleep a wink. When I asked about it I was told to sleep with her in my hospital bed…”

“Short staffing numbers and a full maternity ward meant there was inconsistent advice, and I felt like it was dumb luck as to what advice and care was given. Medications were dispensed ad hoc and I would go for hours without being checked on. I didn’t know what was normal or what questions to ask.

“Unfortunately, the staff at Wellington Hospital were very hit and miss, from the lovely midwife who sat with us for hours, to another midwife that yelled at us for doing something the way we had been told by a previous midwife. We were very pleased to leave and go home. The staff were clearly under a lot of pressure, gave inconsistent advice, were either really rude or really lovely. Things they should have picked up (including my son’s tongue tie) were missed.”

“The care in hospital was poor. Midwives giving mixed advice… A general lack of

(Palmerston North Hospital)empathy, told to get over a traumatic birth the day after it happened. “

“The postnatal care I received at the hospital was appalling, barely any contact with staff and when I did get to see someone they were extremely unhelpful and clearly overworked.”

“More staff at Kenepuru when they have a full house. Four babies all tongue tied meant in my one night stay I hardly got any support as midwife was too busy helping them. I would press the buzzer as my baby was crying/coughing and I couldn’t get up (c section so hard to get out of bed quickly) and no one would come for at least 20-30mins.”

“Terrible post birth experience on the maternity ward. My twins were in SCBU. I didn’t get the opportunity to meet my babies for more than 12 hours after they were born, let alone hold them. They were stable, just slightly preterm but I had an epidural which had prolonged effect and couldn’t walk, the ward staff were too busy to take me down the hall in a wheelchair in the night, so I had to wait until morning to meet them. I was discharged day two post c-section (my third c section)

because the ward was full and my babies weren’t with me. No one on the ward was particularly helpful – I wasn’t offered assistance with a wash despite being bed bound and covered in blood from placental abruption and crash c-section. Hutt Hospital maternity ward needs better staffing!”

Shared rooms postnatally do not meet new mother’s needs.

Shared postnatal rooms became policy when women were “confined” to hospital for 10 – 14 days after giving birth and their babies were “confined” to the hospital nursery. This model has persisted despite, a drastic reduction in the length of inpatient postnatal care, babies now rooming -in and longer visiting hours. It is totally inappropriate for new mothers to have to share a room with any other mothers/parents and babies and their visitors. The MoH must require existing facilities to upgrade to single rooms and any new facilities to comprise of single rooms only.

“… not having shared rooms!! Both of us (

(Wellington Hospital)pn mothers) had emergency c sections and it was really disruptive having two very dependent people share a room (and bathroom facilities!)”

“With my firstborn I was transferred to Palmerston North hospital due to complications during birth and after spending one night in hospital, I couldn’t wait to get back to Levin. The food there is disgusting and sharing a room isn’t good for rest or privacy.”

Postnatal wards need to be better set up for new mums and sleep (too noisy).”

(Shared room Dunedin Hospital)

“However being in a maternity ward in shared room with multiple other women and their babies while recovering from a traumatic birth, which resulted in an epidural, spinal and emergency C-section and a baby in NICU wasn’t ideal. It’s heartbreaking knowing you can’t get to your baby when you want but hearing all the other babies around you cry.”

“More space in

(Wellington Hospital)hospital so not kicked out of delivery suite the second the baby was born, and not put in a very noisy shared room as an overwhelmedfirst time mum.”

“I had to stay on the maternity ward… lack of sleep due to others (in the room) hard when I had to get up 3 hourly to feed the twins (in NNU).”

“The only good thing they did was offer me and my new son our own room instead of being farmed into a room with 3 other women and newborns. That was some salvation after a very exhausting delivery.”

“I could have done with some postnatal care before going home to my other kids. It’s hard to rest in hospital when you’re sharing a room with someone else. The

person I shared with had hundreds of visitors as well as her young toddlers there. I couldn’t wait to get home.”

We’ve just become a family – postnatal care should accommodate fathers/partners too.

Single rooms in the immediate postnatal period would not only support healthy transitions and bonding for new families, they would potentially reduce workload for the demonstrably overworked staff in our postnatal facilities.

“I think it should be a given that the father or other family member can stay in hospital with you post baby.”

“Scared, having anxiety attacks, gravely sick and begging for my husband to stay and help me care for

(North Shore Hospital)baby was met with a “NO – against policy and only in exceptional cases”. Without hissupport I felt isolated, alone, scared and became unattached from my baby.”

“…having your partner being forced to leave the hospital because it’s a “woman’s” ward is stupid. He has just become a father for the first time! He would have loved to be a part of the first night.”

(Waikato Hospital)

“Was not happy that my husband could not stay in

(Middlemore Hospital)hospital overnight. After a c-section and with a brand new child, husbands should be allowed to stay. They should be able to stay anyway!!!!”

“In Christchurch there needs to be an option for partners to stay and help in the night.”

“The first night in hospital I was not allowed to have my partner stay as per policy and unfortunately nurses and midwives working were understaffed and very busy so … there was not the time to support me with breastfeeding.”

“I also found that there was a lack of support (because of resourcing, I felt) for the night time when my husband was unable to stay, yet I’d just given birth, had heavy postpartum bleeding and both a catheter and canular so doing anything (showering, changing/feeding baby etc) was difficult.”

“The first night with your first baby is terrifying and lonely. It would be nice if partners were encouraged to stay rather than encouraged to go home.”

“Would be fantastic if partners could stay all night with you after a c-section. I couldn’t move to pick up my crying baby and the nurses were busy, took ages for them to come resulting in distressed mum and baby – that didn’t need to happen.”

“My experience in hospital on the first night after my child was born was truly awful for me. As is usual with newborns, he didn’t want to be put down, he just wanted to be held. This meant I didn’t sleep for close to 48hrs (having laboured through the previous night). I would have greatly benefited from my husband being able to stay the night to help me with our son. The midwives and nurses were good but they were simply stretched too thin.”

I was discharged before I was ready.

There is very little evidence of partnership in the provision of postnatal care. Women were discharged from both Delivery Units and Postnatal Wards because either the facility needed the bed they were in, or to relieve pressure on the skeleton staff or simply because “it is policy”. There is no consideration taken of the duration of labour, or when the woman (and her partner/support person) last ate or slept, travel distance to home or the primary birthing unit, time of the day or night. They are simply told to leave.

“…being kicked out the door of the hospital by the hospital midwives. I had a terrible night 2 with my baby and in the morning, a midwife came in and said “you are going home today” and I said I didn’t feel comfortable with that. We left

(Dunedin Hospital)hospital exactly 48 hours after my child was born. It was very stressful. I didn’t feel ready or comfortable with breastfeeding and I felt very attacked.”

At “Chch Womens Hospital you have to leave hospital within 48 hours post c-section. Hospital, staff really push you to be out.”

“I was very sore and 2 hours after delivery I had to drive to a different centre.”

“I was not happy with the postnatal care at Christchurch Women’s however as felt rushed out…”

“Having to be out of the delivery room within 2 hours of the baby being born. Having to leave the main hospital with an

(Christchurch Hospital)hours old baby to go to an out area hospital due to bed shortage or (because these) “are the rules”.”

“I was discharged from hospital 3 hours after birth with a 37 week old baby and we went to a Birthing Centre. The baby would not breastfeed and as a result lost a lot of weight, suffered from jaundice and had to be readmitted into hospital. He didn’t behave like a full term baby and unfortunately nobody was able to recognise this for quite some time.”

“The hospital care

post delivery was average. I only stayed 9 hours – felt booted out. I wasn’t fed – they somehow forgot to supply a meal so I had to forage for toast. The hospital facilities are poor (TDHB) badly needs an upgrade, it was freezing at night…”

Primary Birthing Units much better at meeting the needs of new mothers and babies

It was a relief to read positive comments about women’s experiences in many of the Primary Birthing Units throughout the country. We urgently need more of these facilities for birthing and postnatal mothers/whanau.

“Wairau Hospital in Blenheim was great, there was no rush to leave and a focus on supporting breastfeeding.”

“Aftercare was at Helensville Birthing Unit. Great free facility especially for me as a first time mother. Getting meals made for me and helpful tips plus 24 hour care whilst recovering and learning to breastfeed and handle my newborn.”

“The birthing unit in Paraparaumu was fantastic. After the horror of Wellington Hospital it was a safe haven for me.”

“The birthing centre we went to (provided) amazing care. So many support services there and a nice environment post birth. The feeding support was brilliant there.”

“Papakura Maternity Unit Midwives were amazing and attentive for the 48hours I was there.”

“Had 3 days at Clutha Health First in maternity and was cared for over and above!! … we were then provided with the utmost care. Even the relieving night staff midwife was amazing providing the best breastfeeding support I’ve ever had with a newborn.”

“All round great services at Warkworth Birthing Centre. Food, care, breastfeeding support all wonderful.”

“Charlotte Jean in Alexandra is amazing for postnatal care.”

“Just wish Tuatapere Maternity Home was never closed as it was an amazing place that cared well for mums.

“The Te Awamutu Birthing Centre was absolutely amazing. The midwives were kind and encouraging without being intrusive. I always felt I could ask for help and I was well cared for medically.”

“Lumsden Maternity Centre are the best and I would highly recommend to anyone.”

“More facilities like Kenepuru where I received amazing support from midwives while transitioning post c-section from the hospital to home.”

“Women and their partners deserve choice when it comes to the type of care they receive. To me, this means funded birthing centres in all major cities at a level that adequately caters for the population. I would hate to live in a city where my only real choice for birthing is in a hospital, we are lucky in Hamilton.”

It’s not over yet…

To ensure the health and wellbeing of mothers and babies in the postnatal period, there is an urgent need to define what a quality postnatal service consists of and to adequately fund this service. Models that do work, like PBUs, are few and far between and are being closed at a faster rate than they are being built. It is clear that there is an urgent need for increased staffing and funding of in-patient postnatal care. The funding structure for midwives who provide home-based postnatal care needs to be changed to allow for more postnatal visits in the first week or two post birth and audit measures need to be put in place to ensure that women are receiving these visits. Postnatal care needs to be planned with women and these plans needs to be negotiated and revised according to each mother and baby’s need as the postnatal period progresses. The long-term costs to individual women and their families and to our health services, of underfunding and underproviding postnatal care are not sustainable.

One woman succinctly summed up the issue…

“The best thing about our maternity care has definitely been the Midwives, for the most part, they are amazing, undervalued, working above and beyond and absolutely priceless. It’s the supporting services I believe that need putting in place. I also believe the support given in hospitals needs to be looked at, staff shortages, and hospital midwives not all being on the same page don’t make for the best care. A new Mama (whether it is her first or her tenth baby) needs time, she needs to be listened too and she needs to be supported in areas that she is struggling with – this is hard to do when every new midwife has a different view and when the midwives themselves, are stretched beyond what is a reasonable work load. While we have some wonderful people and some wonderful things going on in our maternity care, we still need to do better by our Mamas, babies and their whānau. After all, what is more important that empowered Mamas, who are RESPECTED, well supported, fully informed and know where to get any support they need? The better our maternity services are, the better outcomes our Mamas, babies and whānau are going to have. Some of this is as simple as women being respected and empowered during their pregnancies, births and beyond – this costs nothing! The rest may cost, but will save so much down the line. The messages that are put out there (eg breast-feeding is best for baby and Mama) are not backed up with the support needed…It’s not good enough.”

Once again a BIG thank you to all the women who took the time to share their experiences.

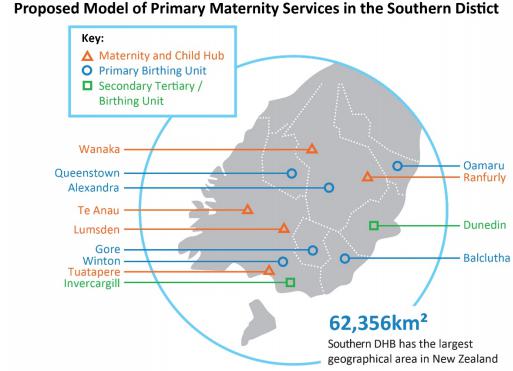

Southern District Health Board Announces Closure of Lumsden Maternity Unit.

In August it was announced that the Southern District Health Board (SDHB) has decided to close Lumsden Maternity Unit.

SDHB released the “Report: Primary Maternity Project” in May 2017, that provided a background for their decisions regarding funding of primary maternity services throughout their catchment.

85% of women in the SDHB catchment birth at either Dunedin Hospital (Queen Mary Maternity) or Southland Hospital (in Invercargill) and many travel hundreds of kilometres to get there. Currently SDHB funds seven primary maternity facilities in rural and remote rural locations: Oamaru, Alexandra, Balclutha, Gore, Winton, Lumsden and Queenstown, but provides no primary birthing facilities in urban Dunedin or Invercargill.

The Ministry of Health Service Coverage Schedule (SCS) requires DHBs to provide or fund primary maternity facilities for urban or rural communities which have:

- 200 pregnancies per year and are 30 minutes from a secondary service

- 100 pregnancies per year and are 60 minutes from a secondary service

The Lumsden area has fewer than 100 pregnancies per year. Over the past 5 years, an average of 29 women per year

| Primary Maternity Facility | Distance to base Hospital | Average births per year in catchment | Births at PBU2014/15 | Transfers to hospital in labour | Postnatal only stays |

| Oamaru | 1.5hrs | 239 | 74 (33.6%) | 6 (8.1%) | 78 |

| Alexandra | 2.25hrs | 336 | 52 (18.4%) | 2 (3.8%) | 115 |

| Queenstown | 2.5hrs | 276 | 65 (25.9%) | 4 (6.2%) | 95 |

| Balclutha | 1.0 hr | 197 | 40 (24.2%) | 3 (7.5%) | 75 |

| Gore | 1.0 hr | 267 | 67 (31.6%) | 8 (11.9%) | 81 |

| Lumsden | 1.0 hr | 66 | 24 (40%) | 2 (8.3%) | 31 |

| Winton | 30 mins | 64 | 37 (60%) | 1 (2.7%) | 145 |

SDHB engaged in a 2-year long consultation and development process before deciding what primary maternity services they would provide in their area. The Report notes that, “International and New Zealand evidence shows that healthy women with low-risk pregnancies who labour and birth in a primary maternity facility have better health outcomes for both mother and baby, compared to those who birth in a secondary or tertiary base hospital.” And goes onto say that, “The consultation feedback showed that women felt there was insufficient information on the benefits of primary maternity services and entitlements to these services. They requested independent and objective information to support decision-making. Many women base their conversations and subsequent decisions on perceived safety considerations, especially the ‘what if’ concerns and distance from secondary/tertiary services.” … “Feedback from consumers, midwives and providers reflected that transport/transfer is a major issue in the Southern District. There is a widely held perception that current systems may not consistently ensure timely transfer. There is variability in mode of transport being authorised or supported by receiving obstetricians, particularly regarding road versus helicopter transport. The complexity of the communication required to arrange a transfer was also identified.” So women and midwives were able to articulate their concerns but it appears that none of these has been addressed. There has been no public health campaign about the benefits and safety of birthing in a primary unit and although SDHB talks vaguely about, “establishing a comprehensive and cohesive maternity transport and retrieval system”.

The DHB appears to have passed responsibility for access to women and their LMCs. “Travel time is a part of the birth plan LMC midwives and expectant mothers would develop together. The majority of women and their midwives are managing this currently, as most are already travelling to birth in (secondary/tertiary) facilities.” Having women plan (and fund) their own travel to base hospitals, rather than establishing emergency transfer systems from the PBUs, seems to be false economy on the part of the DHB when the most recently available annual statistics for both Dunedin and Invercargill hospitals suggest that a percentage of women, manage travel time by choosing elective inductions of labour or elective c-sections.

| 2016 Maternity Outcomes, Dunedin & Southland Hospitals | ||||

| Mode of Onset | Queen Mary Dunedin | Southland Hospital Invercargill | ||

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Spontaneous Labour | 890 | 54% | 656 | 54% |

| Induction of Labour | 444 | 27% | 363 | 30% |

| Elective Caesarean Pre-Labour | 311 | 19% | 194 | 16% |

| Normal Vaginal Birth | 922 | 56% | 724 | 59% |

| Assisted (Forceps/Ventouse) | 226 | 13% | 107 | 9% |

| Emergency (In labour) Caesarean | 194 | 12% | 191 | 16% |

It is frustrating that all our DHBs, including SDHB, seem to be able to find funding for more elective procedures (we know that c- section births cost twice as much as a vaginal birth and that’s without the knock- on costs of the additional care needed by a percentage of mothers and babies following surgical birth), but fail to show innovation, leadership or cohesive support for funding and promoting safe primary birthing options including emergency transfer solutions that would encourage more women to use their local PBU.

SDHB’s proposed model for maternity service provision suggests that women in Lumsden, where the PBU will be closed (and those in areas with no current formal infrastructure e.g. Wanaka and Te Anau), may instead (of PBUs) get “maternal and child hubs.” “While not primary birthing units, these will be equipped and available for urgent births, and integrated with other health services.” Exactly what these “hubs” will offer or even when they’ll be up and running is unclear. “It is possible

that a hub might include rooms for consultations by midwives and other healthcare providers, including visiting specialists, equipment such as a homebirth kit, CTG for monitoring foetal heartrates and contractions, blood pressure monitoring, a resuscitation kit, and IT provisions for telehealth services. A hub may also include offsite maternity and child services, such as breastfeeding and parenting support, and in- home postnatal care.” There is no reason that the services proposed to be provided from the “maternal and child hubs” cannot be offered within a PBU. SDHB needs to make a real commitment to the health of mothers and their babies throughout their catchment by providing primary birthing, emergency transfer and in-patient postnatal care options in facilities that also house the ancillary services of the proposed “hubs”.

Closure of Lumsden PBU is a shortsighted response to: an outdated funding formula; a sparse client base that is spread over a vast area; lack of innovation around funding; inadequate or non -existent education about, and promotion of, PBUs; and a failure to supply, support and co-ordinate primary and ancillary maternity services including emergency transfer services.

Mind that Child, A Medical Memoir

Dr Simon Rowley with Adam Dudding (Penguin Random House 2018)

“To make a diagnosis you need a knowledge of the pathologies that might explain the symptoms and an ability to think laterally and ask extra questions….But first you have to hear what the patient is trying to tell you. That means being polite and kind and empathetic and most of all being a good listener.”

Dr Simon Rowley’s memoir of his professional life from his University years to his role of Paediatric Neonatologist at National Women’s Health is an easy and informative read.

After describing his personal journey into paediatrics, he gives us a brief history of the major breakthroughs, (several of which were made by NZers), as well as the missteps, that have contributed to the relatively new specialty of neonatology. “In recent years the boundary between likely survival and likely death has been hovering around the 23 – 24 week mark. When I was a trainee intern in the 1970s it was heartbreakingly higher… In 1974 nine out of ten babies born under 1000gms at NWH died; by 1994 eight out of ten were surviving.”

He discusses the responsibilities and ethical dilemmas facing neonatologists, “The fundamental question of neonatology is not, “Can we keep this child alive?”, but “Should we…?” “When all prospect of meaningful life for a sick baby is gone…but you have the technical ability to keep them alive for just a little longer, should you do so? For me the answer …is a resounding “no”. To think otherwise is fall prey to the ‘technological imperative’ – the belief that if we have the technology we must use it.”

He also discusses two issues close to MSCC’s heart, partnership between parents and their medical care providers and informed choice and consent. He states that there have been great improvements in the power balance between doctors and consumers, “Doctors are no longer god like figures whose word must not be questioned …today, the patient’s right to know is absolute.” His understanding of partnership and informed choice, however, appear to be weighted in favour of the clinician and informed compliance, “In neonatal care though, doctors have to shoulder some of the responsibility and give parents a firm nudge in the right direction. There are tough messages but if honesty and transparency are balanced with kindness and compassion we can guide parents towards the best option, even when it runs counter to their initial instincts.”

Simon Rowley has extensive experience across a broad field of paediatrics. Early in his career he worked in Paediatric Psychiatry and for 30 years, alongside his work in neonatology at National Womens/Auckland Hospital, he ran a part-time private paediatric clinic and was also, Visiting Paediatrician for the Plunket Family Centres in Auckland.

The Brainwave Trust

In the early

Early Postnatal Discharge

In the second half of his book, he discusses some common paediatric health issues. He also voices his opinion about changes to the structure of the maternity service provision during his professional working life. He laments the policy of earlier and earlier postnatal maternal discharge, stating that these policies “look suspiciously like cost-cutting and corner cutting” “As early maternal discharge became standard practice, I could see that breastfeeding mothers were struggling…In many cases where infants were failing to thrive … the problem could have been avoided if mothers had been able to establish lactation and babies show weight gain prior to discharge from the maternity unit.”

Postnatal Staffing Shortages

He goes on to say, “No one notices initially when midwife staffing numbers are cut back at night-time, but that’s because no one is actively measuring the extra misery suffered by mothers who have to wait longer for help, or the subtle social costs caused by an increase in incidence of postnatal depression.” Our lead article shows that, when asked, women are aware of the pain, distress, breastfeeding problems etc, that are caused by inadequate staffing levels in our postnatal wards.

The Birthing Process

However, we cannot agree with his opinion about birth. Whilst agreeing that “there’s been a tendency to pathologise or medicalise labour and delivery…” he goes on to voice the old medical trope that, “the important thing to remember about childbirth is that it is fundamentally unpredictable … it pays to be ready for things to go wrong. I’m sorry Dr Rowley, but survival of the species is a primal prerogative, mother nature and women’s bodies managed to successfully populate this planet, long before modern obstetrics was developed. Birth is no more unpredictable than any other aspect of human life. Modern obstetrics has indeed fallen prey “to the ‘technological imperative’ – the belief that if we have the technology we must use it.” The nearly routine, overuse of obstetric interventions actively assists things to go wrong and this doesn’t “pay”, it “costs” – mothers, babies and society.

Midwifery Training

He goes on to say that “There is a perception among some doctors that midwives don’t recognize medical complications in pregnancy and labour when they occur because they aren’t looking for them…Doctors receive training in health and pathology while my impression is that midwife teaching emphasizes health only.” The only thing that saves these sentences are his use of the word, “perception” in the first sentence and “impression” in the second. It is, however, irresponsible for a doctor of his standing, to repeat this medical scuttlebutt, instead of taking a bit of time to actually look into the midwifery degree curriculum and midwifery outcomes. He goes on to repeat the unsubstantiated view that, “Unless a new midwife has had a year of training in a high- risk obstetric unit after graduation, it’s unlikely that they will have seen, many (if any) instances of birth going badly wrong.”

The Birthing Experience

Dr Rowley digs himself deeper into seemingly subconscious paternalism when he adds that, “I’ve got nothing against natural delivery, with soft lights, music & herbal tea, but the quality of the birth experience needs to remain a secondary consideration.” And “We (Drs) are not here because we want to take over the natural miracle of birth but because we want to make sure everyone gets through alive.” While actively promoting the fact that the inter-uterine experience of the fetus has a profound impact on the child’s subsequent health and wellbeing, he fails to see that ‘quality’ of the transition from inter-uterine life to (relatively) independent life outside the mother’s body, for mother and baby, has a huge impact on the health and wellbeing of them both. Science confirms that the “unpredictability” of birth would be greatly reduced if the ‘quality’ of the

birthing experience supported the physiological norm. I am outraged by his suggestion that it is “doctors” who make sure that “everyone gets through alive” as if women/parents & midwives couldn’t give two hoots about the outcome, as long as they were able to have a ‘quality’ experience’!

Universal HIV Screening

I have to take Dr Rowley to task over his report of consumer involvement in the development of the Universal, Prenatal, HIV Testing Programme. No-one disputes that, “Identifying the mother’s status in pregnancy is important because there are measures we can take to reduce the risk for the baby to virtually zero.” However his simplification of consumer opposition to universal HIV screening, “They argued that it was an invasion of the mother’s privacy…” is incorrect. “Initially it was hard… to get groups such as Maternity Action (Here, perhaps demonstrating his lack of regard for formal consumer input, Dr Rowley has managed to merge two consumer groups, Women’s Health Action and the Maternity Services Consumer Council) to agree to test the mother.” I wonder if he actually listened to the concerns raised by consumer representatives? Consumer reps questioned the health and cost benefits of testing 100% of pregnant women, when the numbers of women testing positive for HIV for the first time, during pregnancy is incredibly low. ( There were only 9 cases in the five-year period from 2010–2014, all of whom were migrant women from countries where HIV rates are high. Any competent LMC, would have recommended HIV screening to these women.) A bigger concern to consumers was the rate false positive results (1 in every 1000 tests. i.e. potentially 55+ women per year in NZ/Aotearoa) . Consumer organisations felt that the stress, anxiety together with the potential for, damage to relationships and even physical violence, financial abandonment etc. outweighed the benefits of a universal screening programme that would diagnose just two HIV+ women per year (who were likely to have been offered testing anyway). Informed choice was an additional concern. Initially, the proposal was to simply add HIV screening to the first trimester antenatal blood tests. As Dr Rowley says, “Eventually after a few years of wrangling we managed to have universal testing for HIV at maternal booking as an opt- out choice.” A lot of this “wrangling” involved consumer reps educating the medical representatives on the working group about what informed choice actually requires and eventually getting agreement for the informed opt-out clause. We also believe (and Dr Rowley may agree), that many more babies (and their mothers), would benefit, if the resources allocated to the years of negotiation, reporting, setting up and ongoing costs of this universal screening programme were instead diverted to more postnatal

care during the establishment of breastfeeding or universal, free access to timely tongue tie remediation.

Dr Rowley’s expertise and experience in his field is obvious. We applaud his stated primary motivation for writing the book – to encourage healthcare funders to look at the bigger picture. “I sometimes can’t help thinking as we discharge a baby after having spent the best part of a quarter of a million dollars on them, that perhaps we could be spending a bit more on improving the lives of the parents who will be looking after this child for the next 20 years.”

Brenda Hinton

Research: Intrapartum Administration of Synthetic Oxytocin and Downstream Effects on Breastfeeding: Elucidating Physiologic Pathways.

In our May newsletter we reviewed Michel Odent’s book, “Childbirth in the Age of Plastics”, in which he raised concerns about the side effects of maternal exposure to synthetic oxytocin (SynOT) during labour. MSCC is pleased to see other researchers are investigating this issue. This paper used a literature search of all the research that had in fact, demonstrated a link between SynOT exposure during labour and suboptimal breastfeeding.

The authors’ analysis of these studies showed three pathways by which SynOT exposure during labour can affect breastfeeding:

- Dysregulation of the Maternal Oxytocin system because of the difference between natural oxytocin that is delivered in pulses and the continuous infusion of SynOT into the maternal bloodstream that often leads to desensitization of the mother’s oxytocin receptors.

Women who receive the highest dose of SynOT during labour release the lowest amount of their own endogenous oxytocin in response to their babies suckling in the first few days post birth but often release higher than normal amounts for several months following this. Very high or very low levels of circulating oxytocin are associated with PTSD, depression and anxiety. One of the studies reviewed showed that women who had received SynOT during labour had a 30% increased risk of depression and/or anxiety in the first year of the babies’ lives compared with women who had received no SynOT. - SynOT crosses the fetal blood:brain barrier in Labour

Researchers identified the inhibition of several reflexes, including all those associated with breastfeeding, in babies whose mothers had received SynOT during labour. Researchers showed that exposed babies were less likely to suckle during the first hour post birth and even when they did, they were more likely to “forget” how to latch and suckle in the following days. - Hyperstimulation of the Uterus by SynOT

The smooth muscle cells of the uterus recover between the pulses of endogenous oxytocin that cause labour contractions. However, prolonged (>4 hours) continuous infusion of SynOT has been shown to cause receptor desensitization and/or a decrease in the number of uterine oxytocin receptor cells and shorter breaks between contractions, which in turn can lead to more fetal hypoxia, more c-sections and more chance of delays and disorganisation in initiating breastfeeding for mother and baby.

The research analyzed in this study showed that SynOT exposure during labour negatively impacted the oxytocin mediated process of breastmilk “ejection”; babies’ pre-feeding cues; babies’ breastfeeding reflexes; the duration of newborn awake rest and memory consolidation in the first hour post birth; incidence of immediate and prolonged postbirth maternal:infant skin- to-skin contact as a result of an increased need for c-section and infant resuscitation – all factors that negatively impact the successful establishment of breastfeeding.

Concerns continue to emerge that SynOT infusions epigenetically alter the oxytocin receptor gene leading to changes in the immunological development in the infant gut. Authors of several studies urged that the pre-cautionary principle be adopted. Care providers and mothers should weigh up the benefits of inducing or augmenting labour with SynOT against the growing body of evidence showing a potential for harm to breastfeeding establishment and duration, infant immunological development and maternal bonding and wellbeing, in the first year postbirth.

Cadwell K & Brimdyr K. Intrapartum administration of synthetic oxytocin and downstream effects on breastfeeding: Elucidating physiologic pathways. Ann Nur Res Pract. 2017:2(3);id1024

MSCC Steering Group Meetings – All Welcome

AGM & Monthly Meeting: Tuesday 2 October at MAMA Inc, 13 Coyle Street, Sandringham. 10:00am – 12:00pm

Monthly Meeting: Tuesday 6 November at Birthcare, Titoki Street, Parnell.

10:00 – 12:00pm